Original article

Ukrainian Neurosurgical Journal. 2025;31(3):45-57

https://doi.org/10.25305/unj.330291

1 Spine Surgery Department, Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute, Kyiv, Ukraine

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Punjab Institute of Neurosciences, Lahore, Pakistan

3 Restorative Neurosurgery Department, Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute, Kyiv, Ukraine

Received: 19 May 2025

Accepted: 22 June 2025

Address for correspondence:

Oleksii S. Nekhlopochyn, Spine Surgery Department, Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute, 32 Platona Maiborody st., Kyiv, 04050, Ukraine, e-mail: AlexeyNS@gmail.com

Objective: To evaluate the long-term implant-related complications following anterior-only stabilization of traumatic thoracolumbar injuries and to identify structural and radiological patterns associated with construct failure.

Materials and methods: A retrospective multicenter study was conducted at two neurosurgical institutions (Kyiv, Ukraine; Lahore, Pakistan) between 2000 and 2023. Sixteen patients who underwent anterior stabilization at T11–L2 and developed mechanical complications ≥5 years postoperatively were included. Radiographic analysis (CT, X-ray) assessed signs of construct instability, segmental kyphosis (modified Cobb method), global sagittal balance (SVA), and bone mineral density (Hounsfield units, HU). Neurological status was graded using the ASIA scale; pain was assessed via VAS. A complication severity score was developed based on the type of implant failure. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.5.

Results: The most frequent complications were screw-related failures (87.5%), plate migration (68.8%), and cage subsidence/displacement (31.3%). A direct correlation was observed between the severity of structural failure and kyphotic deformity: the median Cobb angles for high-severity cases reached 57°. Global sagittal imbalance (SVA>50 mm) was present in 31.3% of patients, primarily among those with the most severe failures. Neurological decline occurred in 25% of cases, exclusively in the presence of marked kyphosis or implant migration. A bone density < 135 HU was associated with a higher risk of earlier complication onset (HR = 2.83; p = 0.068). Pain intensity showed only a weak correlation with structural deformity.

Conclusions: Anterior-only stabilization at the thoracolumbar junction provides effective decompression and anterior column support but carries a risk of delayed mechanical complications, particularly in the absence of posterior reinforcement. The cantilever effect remains a key biomechanical vulnerability. Patients with HU < 135 should be considered at an elevated risk. A tailored surgical strategy, meticulous implant positioning, and long-term radiological surveillance are critical. In cases with poor bone quality or suspected PLC injury, posterior stabilization may offer superior long-term outcomes.

Keywords: thoracolumbar junction; anterior stabilization; implant-related complications; cage subsidence; segmental kyphosis; bone mineral density; cantilever effect

Introduction

Surgical treatment of thoracolumbar junction injuries is influenced by a broad spectrum of factors, including fracture morphology, neurological status, patient-specific anatomical conditions, and surgeon preference [1, 2]. The primary objective in managing such injuries is to achieve effective decompression of neural elements while restoring or maintaining spinal stability and alignment, ideally with the minimal number of segments involved in fixation [3].

Advancements in surgical techniques and implant technology have enabled the reliable use of short-segment stabilization using either anterior or posterior approaches. Single-stage procedures through either approach are now widely considered viable strategies, offering a compromise between stability, invasiveness, and decompression efficacy [4].

The thoracolumbar junction is considered a biomechanically vulnerable region due to transitional loading characteristics, making it a frequent site of traumatic injury [5]. The optimal choice of surgical approach in this region remains debated, primarily centered on two competing principles of spinal trauma surgery [6].

The first advocates for decompression from the side of the injury—typically via an anterior approach—allowing direct removal of bone fragments and reconstruction of anterior column integrity through partial corpectomy, interbody cage placement, and anterior plating [7]. The second favors posterior approaches, which offer biomechanical advantages, safer access, and the potential for indirect decompression with lower complication rates [8, 9]. Posterior transpedicular instrumentation is widely accepted and broadly utilized due to its reproducibility and favorable risk profile [10].

As with any spinal instrumentation procedure, thoracolumbar stabilization carries the risk of complications. These may be influenced by injury characteristics, implant selection, surgical technique, and patient factors. While posterior fixation techniques and their long-term outcomes especially regarding construct failure, hardware fatigue, pseudarthrosis, and alignment loss have been extensively studied, data on implant-related complications following anterior-only stabilization remain scarce [11].

Given the increasing use of anterior-only constructs in select cases, understanding the nature and long-term risks of this approach is critical. Delayed mechanical failure, although less frequent than early complications, may be more challenging to manage and often requires greater surgical expertise than primary fixation [12].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term implant-related complications following anterior-only stabilization of traumatic thoracolumbar injuries and to identify structural and radiological patterns associated with construct failure.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This was a multicenter retrospective observational study conducted between 2000 and 2023. Clinical and radiological data were obtained from two centers: the State Institution “Romodanov Institute of Neurosurgery, National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine” (Kyiv, Ukraine) and the Punjab Institute of Neurosciences (Lahore, Pakistan). The study focused on long-term mechanical complications following anterior-only stabilization of thoracolumbar junction trauma. All patients provided informed consent for the processing of their data in compliance with institutional and ethical requirements.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

- History of thoracolumbar junction trauma (T11–L2) surgically treated via a ventrolateral approach with anterior-only stabilization;

- Availability of adequate clinical and surgical records to assess injury characteristics and treatment parameters;

- Age ≥18 years at the time of surgery;

- Minimum interval of 5 years between the index surgery and the documented complication;

- Presence of follow-up imaging (radiographs and/or CT) sufficient to assess mechanical construct failure.

While preoperative and early postoperative imaging were desirable for comparative assessment, they were not a strict requirement to preserve the inclusion of cases with long-term follow-up.

Exclusion criteria

- Documented infectious or inflammatory complications in the postoperative period;

- Any reoperation or revision at the index level prior to the complication being analyzed;

- Presence of malignant disease or any severe decompensated systemic pathology;

- Severe osteoporosis (HU < 80);

- Cognitive, psychiatric, or behavioral disorders precluding clinical follow-up or valid data interpretation.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the identification and classification of long-term implant-related complications following anterior-only stabilization of thoracolumbar junction injuries. Secondary endpoints included the evaluation of associated deformities (sagittal and coronal), changes in neurological status, and subjective pain intensity.

Imaging protocol and measurement techniques

All imaging data were evaluated using RadiAnt DICOM Viewer (Medixant, Poland; version 2025.1, license no. 193060A6).

Segmental deformity

Segmental sagittal kyphosis was assessed using a modified Cobb method, measured between the superior endplate of the vertebra above and the inferior endplate of the vertebra below the instrumented segment [13]. Deformity severity was graded as follows: ≤10° – normal/compensated; 11–20° – mild; 21–30° – moderate; 31–40° – severe; 40° > marked [14].

Global sagittal alignment

The sagittal vertical axis (SVA) was measured as the horizontal distance between a vertical line dropped from the center of the C7 vertebral body and the posterosuperior corner of the S1 body. An SVA ≤50 mm was defined as normal; values >50 mm were interpreted as sagittal imbalance [15].

Bone density assessment

Trabecular bone mineral density was estimated using HU values from native CT scans. An elliptical (region of interest) ROI was placed in the anterior two-thirds of the trabecular part of the L3 vertebral body, avoiding cortical bone. Classification was based on Pickhardt et al. (2011): HU >135 – normal bone density; HU 110–135 – osteopenia; HU <110 – osteoporosis [16].

Patients with HU <80 were excluded due to the high risk of confounding biomechanical instability [17].

Functional and clinical parameters

Neurological function was assessed using the ASIA Impairment Scale [18]. Fractures were classified using the AOSpine Thoracolumbar Injury Classification System [19]. Pain intensity was recorded using a standard 10-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [20].

Statistical analysis

All statistical computations were performed using R version 4.0.5 (R Core Team, 2021) in RStudio version 1.4.1106 (Posit Team, 2025). Continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Between-group comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Time-to-failure analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, with the log-rank test applied for group comparisons. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for complication-free survival in relation to bone density.

Results

Patient characteristics

Following initial screening, 27 cases met the search criteria. Of these, 11 were excluded from further analysis due to factors that precluded objective long-term evaluation. Specifically, reasons for exclusion included: improper implant positioning and/or revision surgery prior to the identified complication (n = 3), postoperative infection (n = 2), confirmed oncological pathology (n = 1), decompensated systemic conditions including diabetes mellitus (n = 2), and severe osteoporosis (n = 3).

As a result, 16 patients were included in the final analysis. The mean age at the time of complication diagnosis was 44.6 years (95% CI: 39.7–49.6), and the male-to-female ratio was 1.7:1. A detailed breakdown of the cohort’s demographic and clinical characteristics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 16)

|

Parameter |

Value (95% CI / range) |

|

Sex |

|

|

– Male |

62.5% (35.4–84.8%) |

|

– Female |

37.5% (15.2–64.6%) |

|

Age at complication diagnosis (yrs) |

45.5 (95% CI: 39–49); range 27–62 |

|

Age at injury (yrs) |

37.5 (95% CI: 29–41); range 19–47 |

|

Interval to complication (yrs) |

9.45 (95% CI: 6.8–11); range 5.2–19.4 |

|

Mechanism of injury |

|

|

– Fall |

50% (24.7–75.3%) |

|

– Road traffic accident |

37.5% (15.2–64.6%) |

|

– Sports-related |

12.5% (1.6–38.3%) |

|

Fracture level |

|

|

– T11 |

12.5% (1.6–38.3%) |

|

– T12 |

31.2% (11.0–58.7%) |

|

– L1 |

37.5% (15.2–64.6%) |

|

– L2 |

18.8% (4.0–45.6%) |

|

Fracture type (AOSpine) |

|

|

– A4 |

68.8% (41.3–89.0%) |

|

– B2 |

12.5% (1.6–38.3%) |

|

– C |

18.8% (4.0–45.6%) |

|

Neurological status (ASIA) |

|

|

– C |

6.2% (0.2–30.2%) |

|

– D |

37.5% (15.2–64.6%) |

|

– E |

56.2% (29.9–80.2%) |

|

Bone mineral density (HU) |

|

|

– HU ≥ 135 (median HU) |

56.2%; 172 HU (95% CI: 141–184) |

To better illustrate the clinical and radiological profiles of the complications described below, selected representative clinical cases are presented.

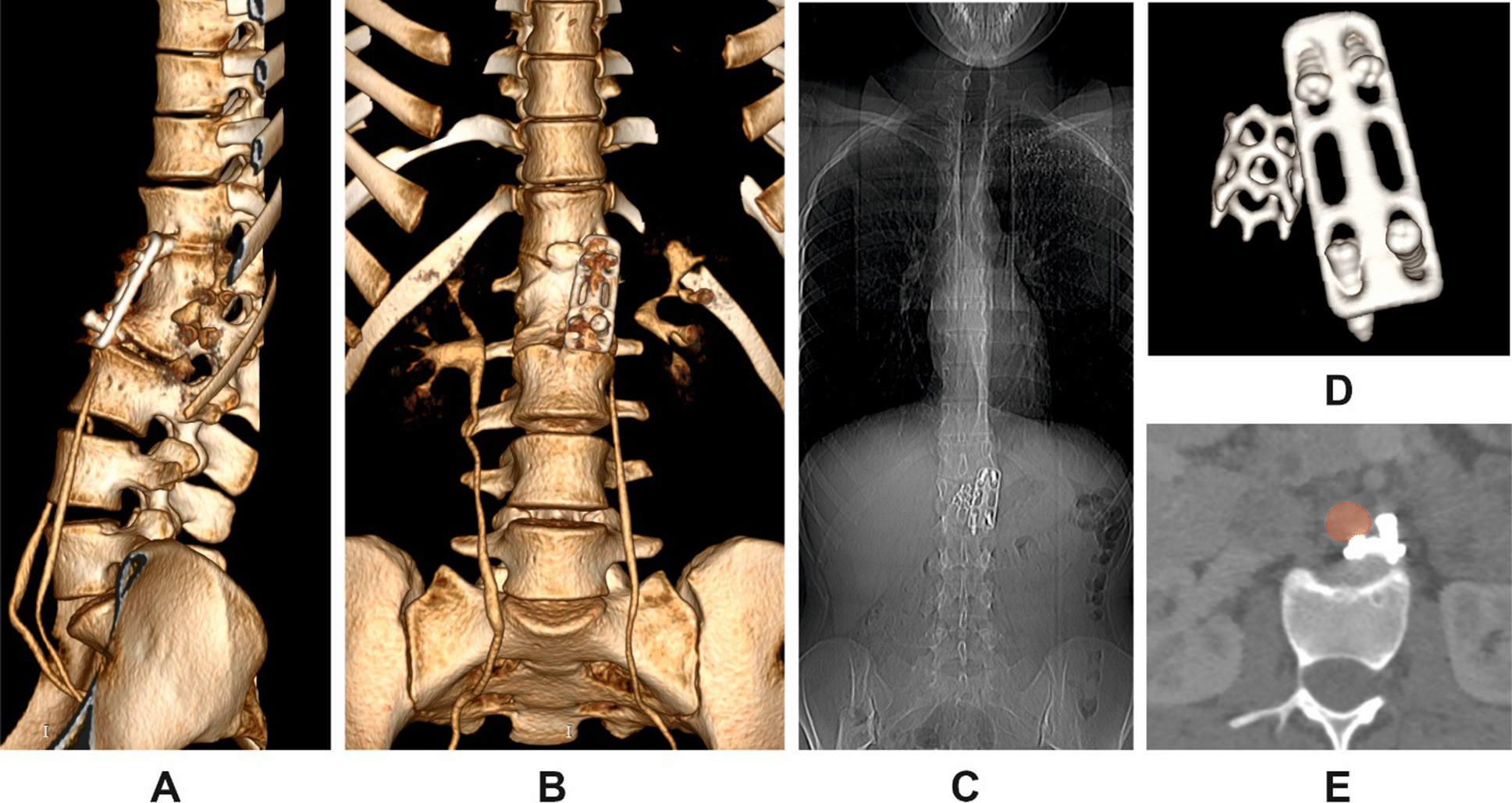

Clinical case 1

Patient K., a 19-year-old female, sustained a thoracolumbar injury in a motor vehicle accident. Сomputed tomography (CT) imaging confirmed a burst fracture of the L1 vertebral body with minor retropulsion of bone fragments into the spinal canal. The patient exhibited no neurological deficit (ASIA grade E). Surgical management consisted of partial corpectomy via a ventrolateral approach, placement of a titanium mesh cage for anterior column support, and stabilization using an anterior plate fixed to the T12 and L2 vertebral bodies with screws.

Following rehabilitation, the patient returned to full physical activity. Five years postoperatively, she began to report intermittent low back pain following physical exertion, which did not require analgesic therapy. At 7.3 years postoperatively, she developed new-onset epigastric pain. After excluding visceral causes, CT of the thoracic and lumbar spine was performed.

CT imaging revealed complete loosening and extraction of all fixation screws, along with dislocation of the anterior plate (Fig. 1 A, B, D). The migrated screws were found in direct proximity to the abdominal aorta, with one causing localized indentation of the vessel wall (Fig. 1E). A pronounced segmental kyphotic deformity at the instrumented level was noted, with a bisegmental Cobb angle between T12 and L2 measuring 39.8°. However, overall sagittal alignment was preserved, presumably due to compensatory lumbar hyperlordosis. No segmental or global coronal deformity was observed (Fig. 1B, C). Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured at 192.26 HU (SD 43.82). On clinical examination, the patient remained neurologically intact. Pain intensity was 3 out of 10 on the visual analog scale (VAS).

Fig. 1. Multiplanar CT reconstructions in Patient K.

A: 3D posterior oblique view of the thoracolumbar junction;

B: anterior 3D reconstruction;

C: anteroposterior scout view;

D: isolated 3D view of the displaced instrumentation;

E: axial view showing displaced screws in close contact with the abdominal aorta (highlighted in red)

Revision surgery was planned, including removal of the anterior implant and screws, followed by posterior transpedicular stabilization. Due to the high risk of intraoperative complications, particularly related to screw proximity to the aorta, vascular surgical backup was scheduled. However, the patient deferred the procedure indefinitely due to family circumstances.

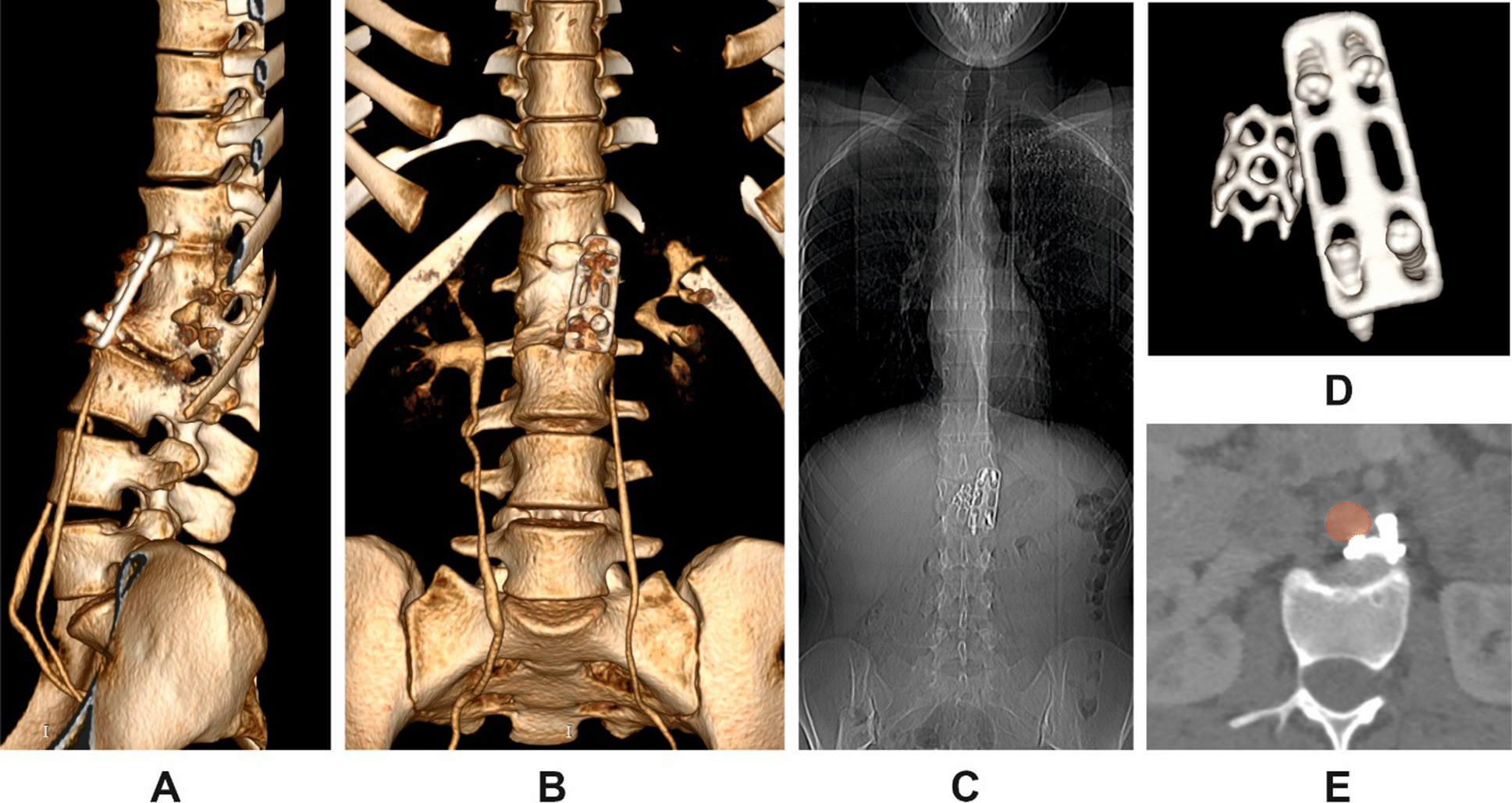

Clinical case 2

Patient H. underwent anterior stabilization of a thoracolumbar fracture at the age of 16 in 2009. Eleven years after the initial surgery, she presented with progressive spinal deformity and chronic lower back pain.

Radiographic and CT assessment revealed implant failure, anterior construct loosening, and severe kyphotic deformity. The measured Cobb angle was 69°, accompanied by global sagittal imbalance (increased SVA) and segmental instability (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Imaging findings in Patient H. prior to revision surgery.

A: 3D lateral reconstruction;

B: lateral scout view;

C: anteroposterior scout view;

D: axial view showing cage subsidence and anterior column failure.

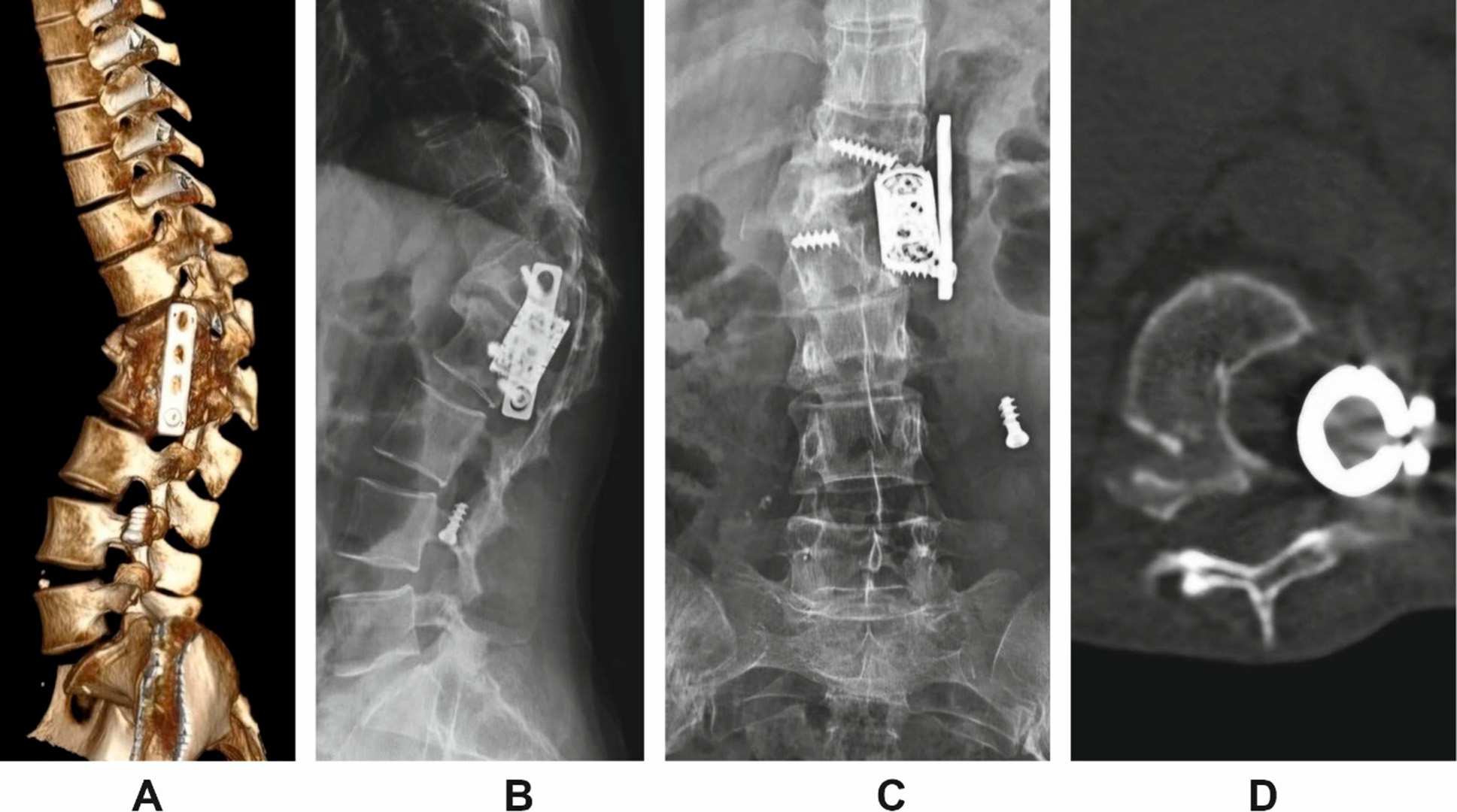

The patient underwent revision surgery via a posterior-only approach. The procedure involved posterior instrumentation with pedicle screws, vertebral body resection, cage placement, and posterior column osteotomy for correction of the deformity. Anterior implants were not revised. Postoperative imaging confirmed restoration of sagittal alignment and segmental stability (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Postoperative imaging following posterior revision in Patient H.

A and B: 3D lateral reconstructions from left and right sides;

C and D: scout views (anteroposterior and lateral);

E: midsagittal CT reconstruction demonstrating correction of segmental alignment.

Complication analysis and classification

To facilitate a detailed assessment of complication patterns and potential causative factors, all confirmed implant-related abnormalities were categorized into the following groups:

- structural complications involving the implanted construct;

- local and global spinal alignment disturbances, with a focus on the operated segment;

- neurological deterioration and pain-related clinical manifestations.

Statistical analysis of the recorded complications revealed the following findings.

Screw-related failures represented the most prevalent complication group, occurring in 87.5% of cases. Among these, screw fragmentation was documented in 6 patients (37.5%), while extraction of visually intact screws was observed in 9 patients (56.3%). Notably, screw fragmentation was accompanied by screw migration in 83.3% of cases. Only one patient demonstrated an intracorporeal screw fracture without displacement. A combined failure pattern was observed in a single patient, where two screws were fragmented and the remaining two were displaced without structural failure.

Plate-related complications were also present: structural failure (fracture) of the anterior plate was identified in 18.8% of cases, and plate migration in 68.8% (11 patients). In 12.5% of cases (n = 2), a specific failure mode was observed, where the anterior plate had lost its stabilizing function due to screw failure. Still, it remained in its anatomical position, maintaining contact along the vertebral bodies, without frank migration.

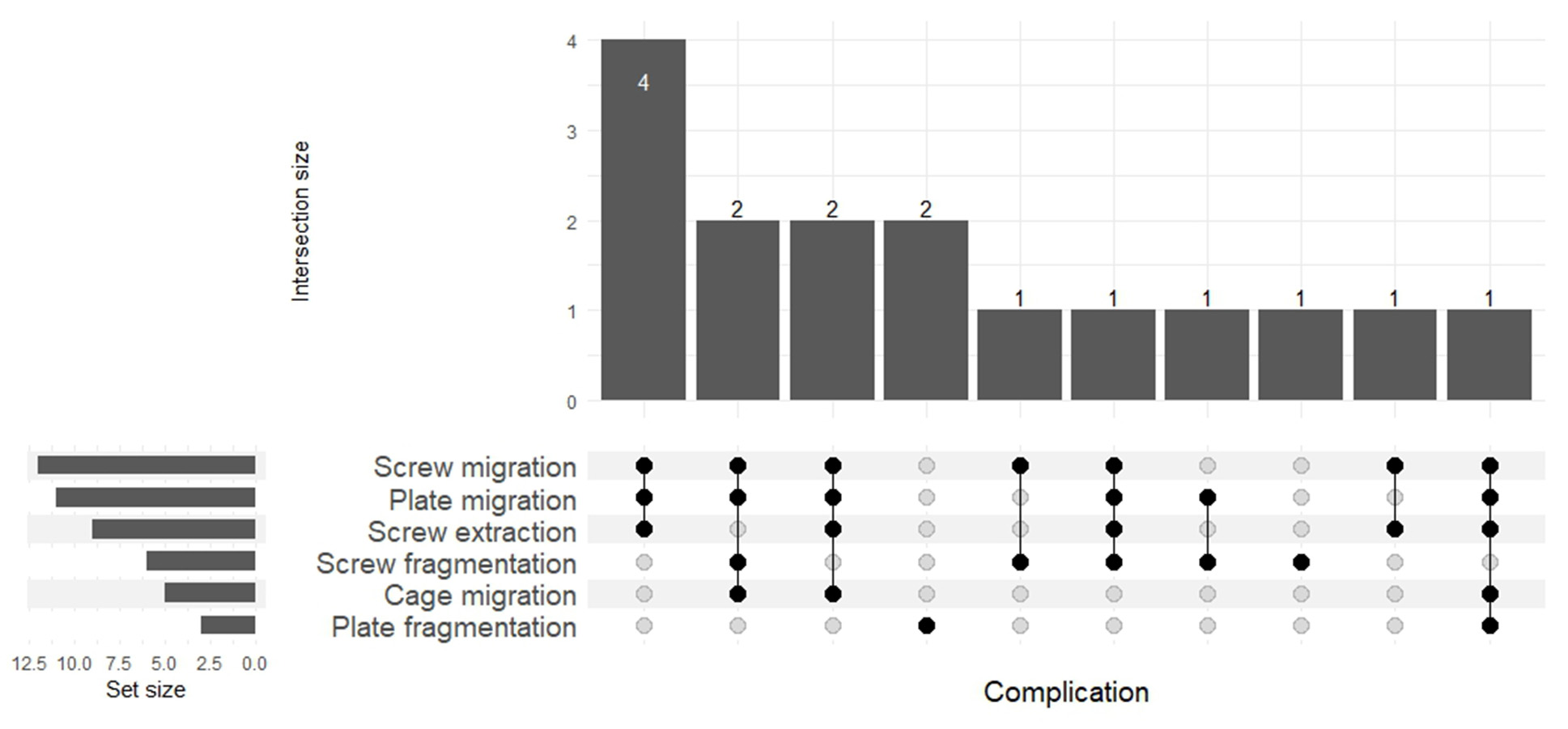

Cage migration, representing the most severe form of anterior construct failure, was identified in 31.3% of cases. In the remaining patients (n = 11), the cage remained within the vertebral body but progressive endplate subsidence and segmental kyphosis were noted. These findings suggest structural weakening of the anterior support zone without gross implant displacement. The frequency and overlap of all implant-related failure types are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Overlap and frequency of implant-associated failure modes (UpSet plot)

Severity scoring of implant-related complications

To provide a standardized framework for evaluating the clinical relevance of implant-related complications, a custom complication severity score was developed. This scale was based on a combination of radiographically confirmed indicators of construct instability. Each complication type was assigned a weighted score reflecting its presumed clinical impact and potential for functional deterioration. These scores were used for subgroup comparisons and correlation analysis with bone mineral density, neurological status, and pain intensity.

Table 2. Scoring matrix for implant-related complication severity based on combinations of structural failure

|

Primary complication ↓ / In combination with → |

Cage migration |

Plate migration |

Screw migration |

Plate fragmentation |

Screw fragmentation |

Score |

|

Cage migration |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

— |

— |

5 |

|

Plate migration |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

— |

— |

4 |

|

Screw migration |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

— |

— |

3 |

|

Plate fragmentation |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

— |

2 |

|

Screw fragmentation |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

1 |

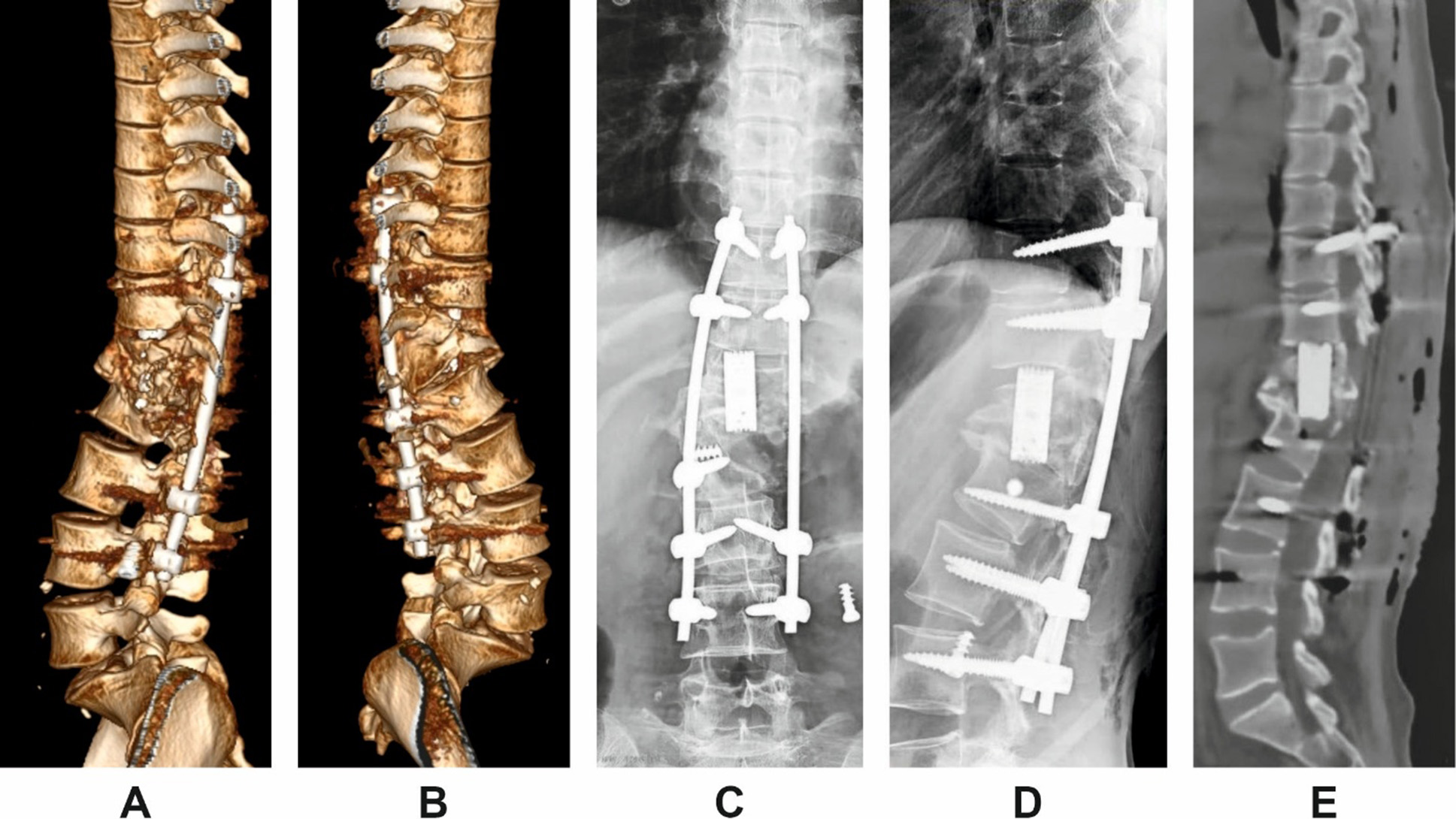

Segmental sagittal deformity and structural failure

The second group of complications analyzed in this study included secondary deformities within the previously operated spinal segment. The most common manifestation was segmental sagittal kyphosis, observed in 12 patients (75%). Given the biomechanical characteristics of the thoracolumbar junction, all cases were classified as kyphotic deformities.

When analyzing the relationship between implant failure patterns and segmental deformity, the following trends were noted:

- Cage migration (score 5) was associated with sagittal deformity in 100% of cases;

- Anterior plate migration (score 4) led to kyphotic deformity in 83.3% of cases;

- Lower-grade structural failures (scores 3, 2, and 1) demonstrated segmental kyphosis in 50%, 50%, and 0% of cases, respectively.

Due to methodological constraints, it was not feasible to precisely compare the degree of kyphotic deformity with early postoperative alignment. Nonetheless, the available data allowed for a descriptive assessment of actual segmental deformity and its relationship to implant failure characteristics.

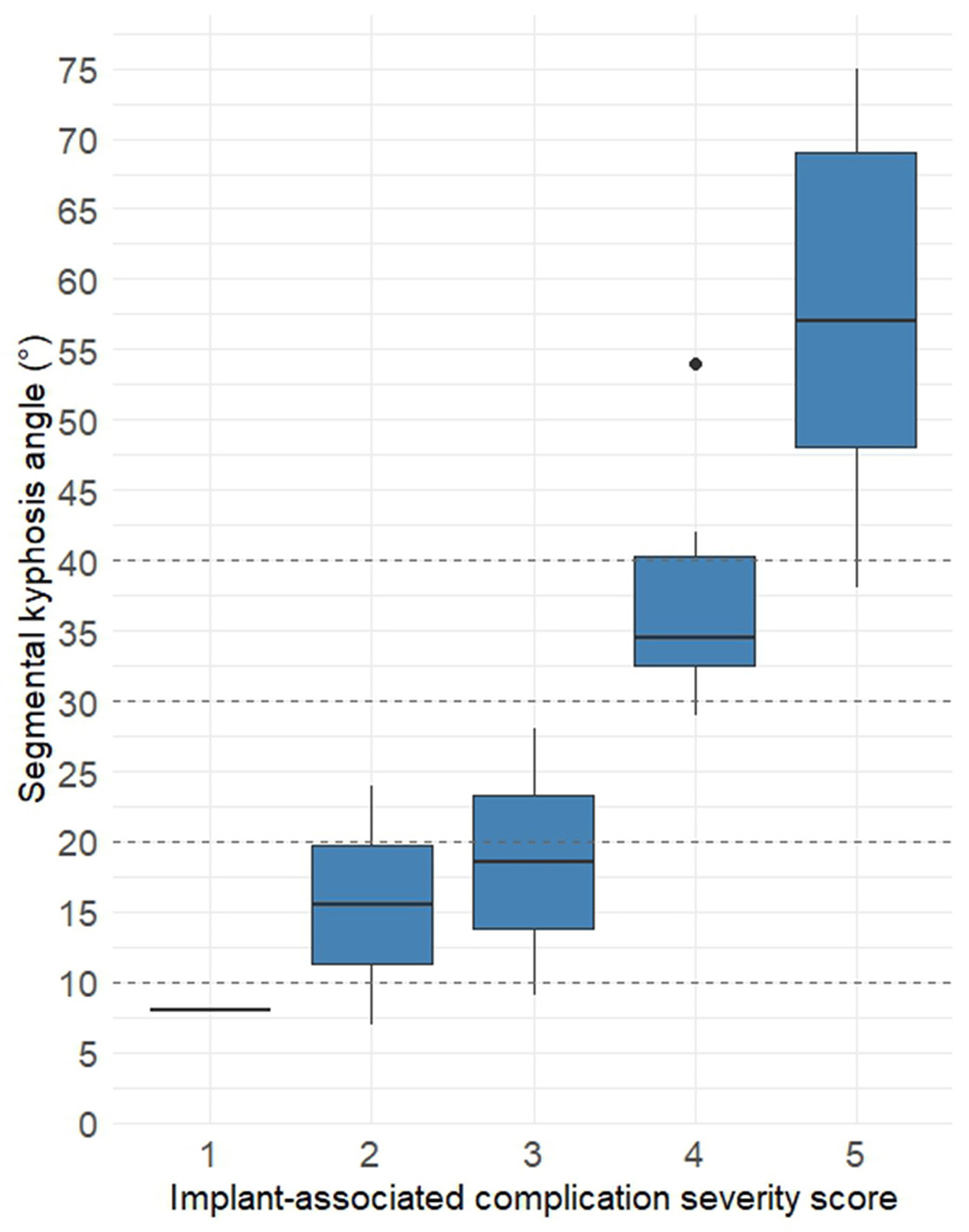

Quantitative analysis of the bisegmental Cobb angle revealed a linear increase in deformity severity in relation to complication score. The most pronounced deformities were recorded in patients with scores of 4 and 5, with median angles of 34° (IQR: 32–40°) and 57° (IQR: 48–69°), respectively. In contrast, an isolated intracorporeal screw fracture without displacement (score 1) did not result in significant sagittal collapse — the angle measured 8°, corresponding to a compensated or minimal deformity.

These findings suggest a direct relationship between the structural severity of implant-related failure and the degree of posttraumatic segmental kyphosis. The association is visualized in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Segmental kyphosis angle (in degrees) relative to implant-related complication severity.

Notes. Boxplots represent median values and interquartile ranges of the bisegmental Cobb angle in each severity group. Dashed lines indicate threshold values for clinical grading of kyphotic deformity.le

Global sagittal balance and its association with implant failure severity

The influence of implant-related complications on global sagittal alignment was of particular clinical interest. Despite the presence of substantial local segmental kyphotic deformity in the majority of patients, analysis showed that signs of global sagittal imbalance, as defined by the sagittal vertical axis (SVA), were present in only 31.3% of cases.

Importantly, sagittal imbalance was found almost exclusively in patients with the most severe implant-related failures—those assigned a complication severity score of 5. Only one case of sagittal imbalance occurred in a patient with a score of 4. No signs of global malalignment were observed in patients with lower complication scores.

Several factors may explain this observation:

- First, the most extreme angular deformities were documented in patients with 5-point complications, potentially exceeding the spine’s capacity for sagittal compensation.

- Second, the nature and progression of the deformity appear to differ based on the type of structural failure. For example, cage migration may lead to rapid loss of anterior support and more abrupt segmental kyphosis. In contrast, plate migration—in cases where interbody support remains intact—may result in slower progression, allowing more time for the development of compensatory mechanisms such as lumbar hyperlordosis or pelvic retroversion.

Two representative cases provide support for this hypothesis. In one, a patient with a bisegmental angle of 48° and a complication score of 5 exhibited a marked increase in SVA, consistent with decompensated sagittal balance. In contrast, another patient with a Cobb angle of 54° and a score of 4 demonstrated preserved sagittal alignment, suggesting successful compensation.

Segmental coronal deformity

In contrast to sagittal deformity—which, in most cases, represented the primary radiographic manifestation of construct failure—segmental coronal deformity was observed far less frequently, being documented in only 25% of cases.

Notably, there was no consistent correlation between the presence or severity of coronal deformity and the overall complication severity score. Specifically, coronal malalignment was identified in two patients with a score of 3 and in two others with a score of 5 (see Fig. 2). In the remaining cases, even in the presence of significant sagittal kyphosis, the coronal profile of the operated segment remained essentially preserved (see Fig. 1).

The likely mechanism underlying the development of coronal deformity in these patients was presumed to be asymmetric loss of structural support, possibly due to unilateral screw failure or cage subsidence. This assumption is supported by detailed radiographic analysis of individual cases, in which isolated implant loosening on one side appeared to precede the onset of coronal angulation.

Neurological decline associated with implant failure

The third group of complications addressed in this study involved neurological deterioration as a potential clinical manifestation of long-term anterior construct failure. A decline in neurological status was documented in 4 of 16 patients (25%).

In three cases, the ASIA grade worsened from E to D, and in one case from D to C, reflecting the development of new or progressive neurological deficits during long-term follow-up.

Analysis of complication severity in these patients revealed the following distribution:

- Two patients with neurological decline had complications classified as score 5;

- One patient had a score of 4;

- One patient had a score 3, primarily due to screw migration.

- It is notable that all patients with neurological deterioration exhibited relatively high segmental kyphotic angles:

- In the two score 5 cases, kyphosis measured 75° and 69°, respectively;

- In the score 4 case, the angle was 42°;

- In the score 3 case, although the sagittal deformity was moderate (28°), a concurrent coronal deformity of 34° was present, which may have contributed to neural compromise.

Despite these findings, meaningful statistical analysis of neurological outcomes was limited by the small sample size, which precluded definitive conclusions regarding causality or predictive risk.

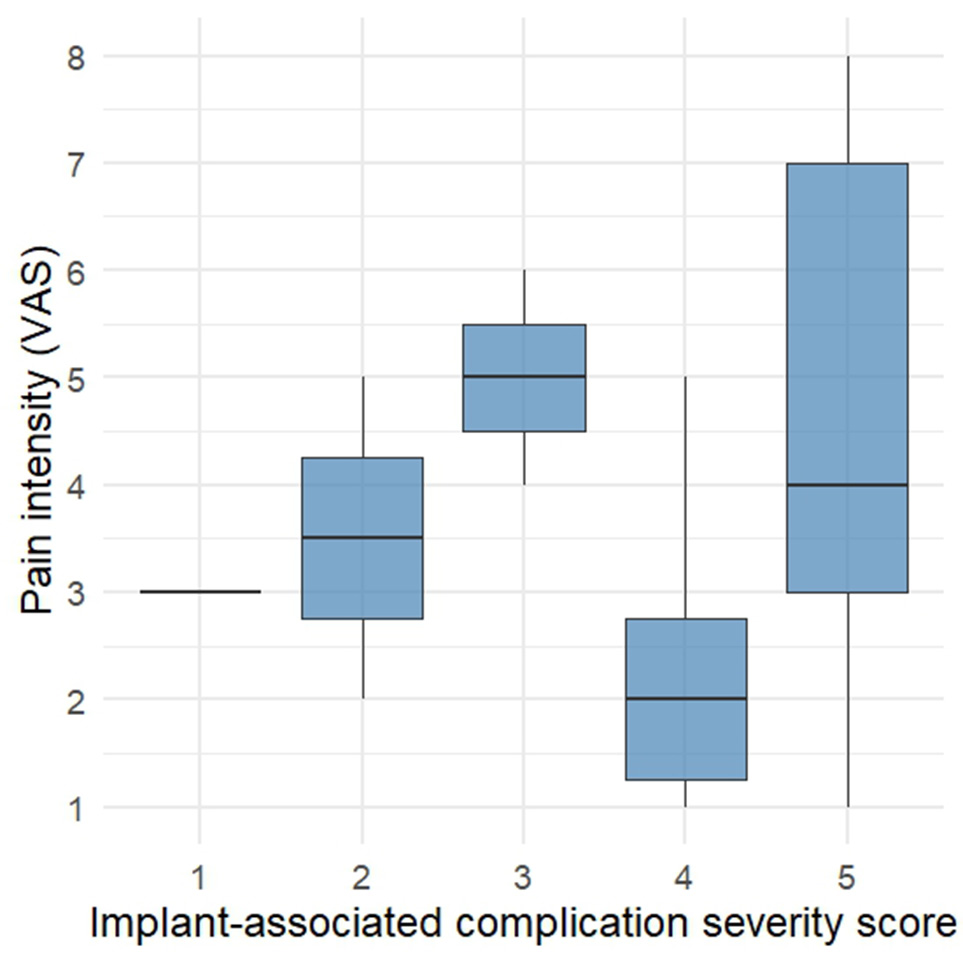

Pain intensity and its clinical correlation

Among all the parameters assessed, pain intensity proved to be the most variable and least correlated with the structural manifestations of complications categorized into the first two groups. Analysis of VAS scores demonstrated that 56.2% of patients reported mild pain, 31.2% reported moderate pain, and only 12.5% experienced severe pain.

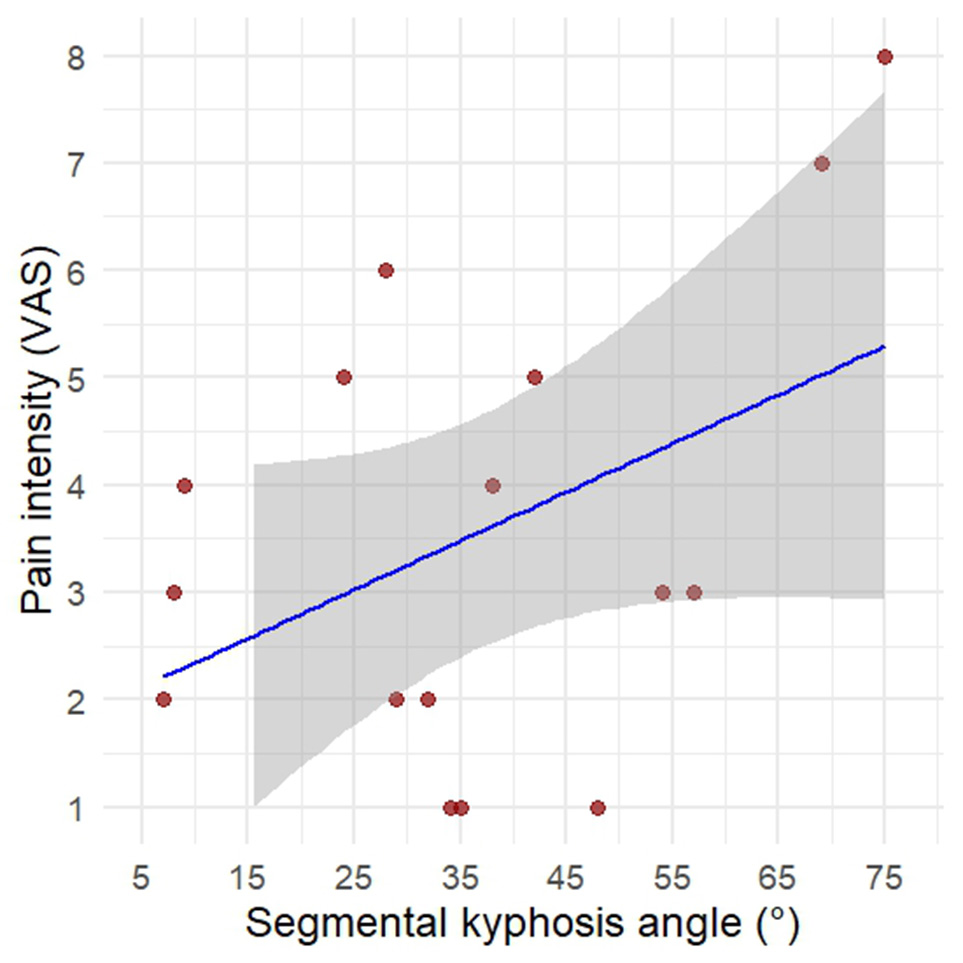

Attempts to identify a statistically significant relationship between pain severity and structural parameters of implant failure were unsuccessful (Fig. 6A). Moreover, it is worth noting that in one case, where the only radiographically confirmed sign of implant instability was an intracorporeal screw fracture (assigned complication score = 1), the progressive onset of pain was the primary reason for performing follow-up CT imaging, which was conducted 6.5 years after the initial surgery.

A B

B

Fig. 6. A - Distribution of pain intensity (VAS) by complication severity score. B - Correlation between segmental kyphotic angle and pain intensity (VAS).

Similarly, segmental sagittal deformity exhibited only a weak correlation with the severity of pain symptoms. Statistical analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient showed no significant association (ρ = 0.23; p = 0.38). While an overall trend toward increasing VAS scores with greater deformity angles was observed, the severity of pain was not consistently proportional to the anatomical degree of kyphosis.

This variability may be attributed to the influence of several additional factors, including individual differences in pain threshold, the presence of concurrent degenerative changes in adjacent structures, and variations in compensatory mechanisms such as postural adaptation or segmental stiffening. These factors must be considered when interpreting the clinical significance of pain in the context of long-term implant-related failure.

Bone quality and its association with long-term construct failure

As a potential factor influencing both the timing and nature of implant failure in the long-term postoperative period, we investigated BMD using CT-based HU analysis. This hypothesis was driven by the observation that, in cases of technically improper implant placement, complications tend to become clinically apparent much earlier.

In contrast, even when anterior instrumentation is placed correctly, the long-term mechanical integrity of the bone–implant interface may be substantially influenced by the quality of local cancellous bone. Progressive trabecular rarefaction, combined with continuous micro-motion at the implant interface, may ultimately lead to critical stress concentrations at points of contact between the implant and the vertebral body. This biomechanical vulnerability can lead to progressive failure of fixation, even in the absence of any technical errors during the initial surgery.

Therefore, bone mineral density should be considered a potentially modifiable risk factor for delayed mechanical failure following anterior spinal stabilization. Our findings provide preliminary support for this hypothesis (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Kaplan–Meier curves showing the time to implant-related complications in relation to bone mineral density (Hounsfield units, HU)

According to the results of Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, a HU value < 135 was associated with a trend toward increased risk of earlier complication onset. The calculated hazard ratio (HR) was 2.83 (95% CI: 0.93–8.67; p = 0.068), suggesting an approximately threefold increase in risk among patients with lower bone density. Although statistical significance was not reached, the direction and magnitude of the observed effect point to a clinically meaningful association between reduced BMD and construct failure.

Discussion

The results of this retrospective analysis of the long-term postoperative period highlight several key aspects related to the use of isolated anterior approaches for stabilization in thoracolumbar junction injuries. Despite the theoretical advantages of this strategy—such as direct decompression of the spinal canal, restoration of the anterior load-bearing column, and minimization of the number of instrumented segments—the identified complications point to the presence of specific, including delayed, risks that must be carefully considered when selecting the surgical approach and planning postoperative monitoring.

Mechanical stability of the construct and its failure mechanisms

One of the most significant findings in our cohort was the high incidence of mechanical complications related to fixation elements—primarily screw loosening and plate migration. These results are consistent with previously published data. Early generations of anterior fixation systems (e.g., AO-ATL-P) were characterized by limited rigidity of the screw–plate interface, which often led to loosening and implant migration within several years postoperatively, occurring in nearly one out of five cases [21]. Improvements in implant design (e.g., ATLP, Synthes) have led to more favorable outcomes: in the series by Wilson J. A. et al., screw breakage occurred in only 3.2% of cases, with no reported instances of pseudarthrosis [22].

A large meta-analysis involving over 700 patients demonstrated that revision surgery due to mechanical failure was required in 10.8% of patients following isolated anterior fixation, compared to 4.7% after isolated posterior fixation. The overall complication rate was 30% and 14%, respectively [23]. This disparity is commonly attributed to the fact that although anterior constructs offer excellent axial support, they are less resistant to shear and rotational forces, particularly in cases of poor bone quality or suboptimal preparation of the vertebral endplates. Excessive loading on the anterior implant without supplemental posterior support may lead to micromotion at the screw–bone interface, resulting in osteolysis and, ultimately, clinically significant implant migration. The timely and solid formation of an interbody fusion plays a critical role. As the graft consolidates, axial loads are gradually transferred from the hardware to the bone, thereby reducing the risk of implant fatigue and failure [24].

While advances in implant design aim to reduce the incidence of implant-related complications, outcomes for isolated anterolateral corpectomy remain inconclusive [25]. Locking plates can reduce the frequency of screw migration but do not prevent periscrew osteolysis and eventual load redistribution, which may lead to intravertebral fragmentation of fixation elements. Similarly, telescoping vertebral body replacement systems—introduced to replace traditional cylindrical mesh cages—facilitate implantation and allow for controlled correction of sagittal alignment. However, their lack of dedicated cavities for bone grafting essentially eliminates the potential for forming a stable fusion mass [26]. As a result, complications may not decrease in frequency but instead shift in character, often presenting with delayed onset after a prolonged asymptomatic period.

A critical factor in the biomechanical reliability of anterior-only spinal stabilization—especially following corpectomy—is the cantilever effect. In classical mechanics, a cantilever is a beam anchored at one end and loaded at the other. Similarly, in spinal surgery, an anterior fixation system (e.g., a plate and interbody cage) functions as a cantilevered beam, transmitting significant compressive and bending forces in the absence of posterior support. Under physiological loading—especially during trunk flexion—the entire upper body weight is transmitted through the anterior construct, while posterior elements remain unsupported. This generates a pronounced bending moment in the sagittal plane, concentrated at the cage–endplate interface. Without posterior stabilization, the anterior implant behaves as a fixed lever arm, significantly increasing the risk of cage subsidence, implant migration, progressive segmental kyphosis, and ultimately, loss of global sagittal alignment [27].

As demonstrated by multiple biomechanical and clinical studies, effective load transfer from the patient to the implant system requires minimizing the moment arm and establishing a compressive force across the construct. This configuration enables the interbody cage to participate in vertical load sharing, thereby enhancing overall construct stability [28]. This means that when properly applied, the plate and screws should generate targeted axial compression across the cage, enabling it to participate in vertical load sharing. However, such a configuration is technically demanding and depends on precise implant positioning and meticulous endplate preparation. Moreover, even under ideal conditions, the absence of posterior tension-band support remains a biomechanical limitation: compression can mitigate the cantilever effect to some extent, but cannot fully neutralize it [29].

Kyphotic Deformity and Sagittal Imbalance

Progressive segmental kyphosis emerged as one of the most clinically relevant consequences of mechanical construct instability. In our cohort, kyphotic angles exceeding 40° were strongly associated with combined mechanical failures, including cage dislocation and plate migration. This finding aligns with previously published studies, which emphasize that even minor implant migration can significantly alter sagittal spinal alignment.

While anterior corpectomy with interbody fusion effectively restores anterior column height and corrects local kyphosis in the immediate postoperative period, subsequent failure of secondary interbody fusion or inadequate fixation may result in gradual subsidence of the graft or implant protrusion, leading to progressive kyphotic collapse [25]. The WFNS Spine Committee recommends maintaining the residual kyphotic angle below 20°, underscoring the importance of assessing not only the local angle but also global sagittal alignment parameters, such as sagittal vertical axis (SVA) and pelvic incidence–lumbar lordosis (PI–LL) mismatch [14, 30].

A prospective study by Avanzi et al. demonstrated that even in patients with segmental kyphosis >30°, quality-of-life outcomes may remain satisfactory as long as pelvic alignment and lumbar lordosis are preserved [31]. This is attributed to compensatory mechanisms such as pelvic retroversion and lumbar hyperlordosis, which maintain the center of gravity over the femoral heads and reduce the load on paraspinal musculature. However, in younger patients with high functional demands or in those with baseline hyperlordosis, these compensatory capacities are limited [32]. In such cases, even moderate increases in kyphotic angulation may result in chronic back pain, muscle fatigue, and gait disturbances [33].

For these patients, early detection of correction loss (typically ≥5° compared to early postoperative radiographs) is recommended, along with consideration of posterior augmentation. Furthermore, kyphotic deformity at the segmental level has been shown to increase mechanical stress on both fixation elements and bone–implant interfaces exponentially. This creates a positive feedback loop: the more pronounced the deformity, the higher the mechanical load, and the greater the risk of further implant-related or structural failure [34].

Neurological and Functional Outcomes

Spinal canal decompression achieved via anterior corpectomy is typically radical and durable. In the series by Wilson et al., none of the 31 patients experienced neurological deterioration during long-term follow-up [22]. However, isolated reports in the literature describe late complications such as cage or screw migration into the spinal canal, leading to compression of the dural sac [30]. Delayed neurological decline is usually associated with either significant cage collapse in the setting of severe osteoporosis, or posterior (less commonly lateral) displacement of a long cortical screw inserted at an excessive craniocaudal divergence angle [35]. These events highlight the importance of early postoperative imaging control and meticulous implant placement. Specifically, screws should be positioned within the cortical ring of the vertebral body, and cage endplates should be closely apposed to the adjacent vertebral endplates to minimize the risk of subsidence.

In our series, the incidence of neurological worsening was low. All such cases were associated with major mechanical failures—marked segmental kyphosis (>60°), cage collapse, or spinal canal stenosis due to implant migration. These findings suggest the potential for delayed neural compromise due to either secondary compression or vascular insufficiency related to spinal canal deformation. Biomechanical modeling by Farley et al. [3] demonstrated that segmental kyphosis exceeding 50° may result in excessive spinal cord tension and impaired perfusion [36].

Interestingly, the severity of pain did not always correlate with the degree of mechanical degradation. Some patients with pronounced structural instability reported minimal pain, whereas others experienced significant discomfort in the context of isolated screw migration. Similar observations have been reported in the literature, highlighting the complex and multifactorial nature of post-fixation pain syndromes [37, 38].

Bone Mineral Density and Prognostic Value

Assessment of BMD using HU measurements revealed a significant correlation between lower HU values and increased risk of early implant failure. A prospective analysis by Su et al. demonstrated that patients with HU < 135 had an almost threefold higher risk of screw loosening or cage subsidence [39]. The HU values observed in our cohort are consistent with these findings.

A growing body of evidence suggests that thresholds of <110 HU are critical for predicting posterior fixation failure, while values <135 HU carry similar implications for anterior constructs [40]. This indicates that CT-based HU analysis may serve not only as a tool for assessing fusion status but also as a reliable method for stratifying patients according to their individual risk of mechanical failure.

Limitations

This study has several significant limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 16) limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Although this reflects the low frequency of anterior-only stabilization in thoracolumbar trauma and the rarity of long-term follow-up beyond 5 years, it nonetheless restricts subgroup comparisons and predictive modeling.

Second, the retrospective design of the study introduces an inherent risk of selection and information bias. Incomplete early postoperative imaging in some cases limited our ability to quantify deformity progression over time. While efforts were made to include only cases with sufficient radiological and clinical documentation, variability in imaging quality and follow-up intervals may have influenced the results.

Third, some outcome parameters—particularly pain intensity—are inherently subjective and may have been affected by patient-specific psychological and physiological factors not captured in this dataset.

Finally, the study cohort was limited to two institutions, which may influence surgical technique consistency, rehabilitation protocols, and implant selection. Multicenter prospective validation in larger cohorts is warranted to confirm these findings and further refine risk stratification based on bone quality and implant design.

Conclusion

Anterior-only stabilization for thoracolumbar junction injuries remains an acceptable option in carefully selected clinical scenarios, providing effective spinal canal decompression and restoration of anterior column support while minimizing the number of instrumented segments. However, long-term follow-up demonstrates the presence of specific risks of mechanical failure, particularly in the absence of supplemental posterior support. The most frequently encountered complications included screw loosening, anterior plate migration, and cage subsidence—often accompanied by segmental kyphotic deformity and, in more severe cases, global sagittal imbalance and delayed neurological deterioration.

The cantilever effect constitutes a key biomechanical vulnerability of anterior constructs. Despite ongoing advancements in fixation technologies, the risk of delayed structural failure cannot be entirely eliminated. A Hounsfield Unit value <135 may serve as a prognostically unfavorable marker and should be considered for incorporation into preoperative risk stratification.

Given the multifactorial nature of these complications and their clinical significance, an individualized approach is essential in selecting the stabilization strategy. This includes strict adherence to technical principles of implant placement and long-term radiological surveillance. In cases of low predicted bone quality, suspected or confirmed disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex, or in patients with high functional demands, isolated posterior stabilization appears to be a more favorable option.

This study clearly demonstrates that even technically successful surgical correction of thoracolumbar trauma via an anterior-only approach does not guarantee the absence of long-term complications. In contrast to isolated posterior fixation, where complications tend to be more predictable, easier to identify, and technically simpler to revise, patients treated with anterior corpectomy and stabilization require closer long-term monitoring. These observations raise doubts about the routine use of anterior-only constructs in a broad patient population.

To validate these findings and refine the risk stratification approach, prospective multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are warranted. Additionally, the proposed implant-related complication severity scoring system should be further standardized, verified, and—if necessary—refined or modified, to support the development of evidence-based clinical guidelines for selecting the optimal stabilization method in thoracolumbar junction trauma.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The study was not sponsored.

References

1. Costa F, Sharif S, Bajamal AH, Shaikh Y, Anania CD, Zileli M. Clinical and Radiological Factors Affecting Thoracolumbar Fractures Outcome: WFNS Spine Committee Recommendations. Neurospine. 2021;18(4):693-703. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2142518.259

2. Zhao QM, Gu XF, Yang HL, Liu ZT. Surgical outcome of posterior fixation, including fractured vertebra, for thoracolumbar fractures. Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). 2015;20(4):362-367. https://doi.org/10.17712/nsj.2015.4.20150318

3. Xu J, Yin Z, Li Y, Xie Y, Hou J. Clinic choice of long or short segment pedicle screw-rod fixation in the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fracture: From scan data to numerical study. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2023;39(9):e3756. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnm.3756

4. Rajasekaran S, Kanna RM, Shetty AP. Management of thoracolumbar spine trauma: An overview. Indian J Orthop. 2015;49(1):72-82. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5413.143914

5. Bruno AG, Burkhart K, Allaire B, Anderson DE, Bouxsein ML. Spinal Loading Patterns From Biomechanical Modeling Explain the High Incidence of Vertebral Fractures in the Thoracolumbar Region. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2017;32(6):1282-1290. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3113

6. Ren EH, Deng YJ, Xie QQ, Li WZ, Shi WD, Ma JL, et al. [Anterior versus posterior decompression for the treatment of thoracolumbar fractures with spinal cord injury:a Meta-analysis]. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2019;32(3):269-277. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-0034.2019.03.015

7. Mittal S, Rana A, Ahuja K, Ifthekar S, Yadav G, Sudhakar PV, et al. Outcomes of Anterior Decompression and Anterior Instrumentation in Thoracolumbar Burst Fractures-A Prospective Observational Study With Mid-Term Follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2022;36(4):136-141. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000002261

8. Kim WS, Jeong TS, Kim WK. Three-column reconstruction through the posterior approach alone for the treatment of a severe lumbar burst fracture in Korea: a case report. J Trauma Inj. 2023;36(3):290-294. https://doi.org/10.20408/jti.2022.0075

9. Shokouhi G, Iranmehr A, Ghoilpour P, Fattahi MR, Mousavi ST, Bitaraf MA, Sarpoolaki MK. Indirect Spinal Canal Decompression Using Ligamentotaxis Compared With Direct Posterior Canal Decompression in Thoracolumbar Burst Fractures: A Prospective Randomized Study. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2023;37:59. https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.37.59

10. Moreira CHT, Krause W, Meves R. Thoracolombar Burst Fractures: Short Fixation, without Arthrodesis and without Removal of the Implant. Acta Ortop Bras. 2023;31(spe1):e253655. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-785220233101e253655

11. Vilela A, Couto B, Ferreira D, Cruz A, Azevedo J, Pereira J, et al. Risk factors for failure in short segment pedicle instrumentation in thoracolumbar fractures. Brain Spine. 2025;5:104266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bas.2025.104266

12. Hu X, Barber SM, Ji Y, Kou H, Cai W, Cheng M, et al. Implant failure and revision strategies after total spondylectomy for spinal tumors. J Bone Oncol. 2023;42:100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2023.100497

13. Cobb’s Method For Quantitative Evaluation Of Spinal Curvature: A Review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results. 2023:4153-4159. https://doi.org/10.47750/pnr.2022.13.S06.550

14. Yaman O, Zileli M, Senturk S, Paksoy K, Sharif S. Kyphosis After Thoracolumbar Spine Fractures: WFNS Spine Committee Recommendations. Neurospine. 2021;18(4):681-692. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2142340.170

15. Glassman SD, Berven S, Bridwell K, Horton W, Dimar JR. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(6):682-688. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000155425.04536.f7

16. Pickhardt PJ, Lee LJ, del Rio AM, Lauder T, Bruce RJ, Summers RM, et al. Simultaneous screening for osteoporosis at CT colonography: bone mineral density assessment using MDCT attenuation techniques compared with the DXA reference standard. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26(9):2194-2203. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.428

17. Shu L, Wang X, Li L, Aili A, Zhang R, Liu W, Muheremu A. Computed Tomography-Based Prediction of Lumbar Pedicle Screw Loosening. BioMed research international. 2023;2023:8084597. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/8084597

18. Rupp R, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Graves DE, Guest J, Jones L, et al. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: Revised 2019. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2021;27(2):1-22. https://doi.org/10.46292/sci2702-1

19. Vaccaro AR, Oner C, Kepler CK, Dvorak M, Schnake K, Bellabarba C, et al. AOSpine thoracolumbar spine injury classification system: fracture description, neurological status, and key modifiers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(23):2028-2037. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a8a381

20. Astrom M, Thet Lwin ZM, Teni FS, Burstrom K, Berg J. Use of the visual analogue scale for health state valuation: a scoping review. Qual Life Res. 2023;32(10):2719-2729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-023-03411-3

21. Thalgott JS, Kabins MB, Timlin M, Fritts K, Giuffre JM. Four year experience with the AO Anterior Thoracolumbar Locking Plate. Spinal Cord. 1997;35(5):286-291. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100399

22. Wilson JA, Bowen S, Branch CL, Jr., Meredith JW. Review of 31 cases of anterior thoracolumbar fixation with the anterior thoracolumbar locking plate system. Neurosurg Focus. 1999;7(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.3171/foc.1999.7.1.3

23. P PO, Tuinebreijer WE, Patka P, den Hartog D. Combined anterior-posterior surgery versus posterior surgery for thoracolumbar burst fractures: a systematic review of the literature. Open Orthop J. 2010;4:93-100. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874325001004010093

24. Cheers GM, Weimer LP, Neuerburg C, Arnholdt J, Gilbert F, Thorwachter C, et al. Advances in implants and bone graft types for lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Biomater Sci. 2024;12(19):4875-4902. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4bm00848k

25. Ortiz Torres MJ, Ravipati K, Smith CJ, Norby K, Pleitez J, Galicich W, et al. Outcomes for standalone anterolateral corpectomy for thoracolumbar burst fractures. Neurosurg Rev. 2024;47(1):816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-03049-w

26. Bhat AL, Lowery GL, Sei A. The use of titanium surgical mesh-bone graft composite in the anterior thoracic or lumbar spine after complete or partial corpectomy. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(4):304-309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005860050178

27. Kallemeier PM, Beaubien BP, Buttermann GR, Polga DJ, Wood KB. In vitro analysis of anterior and posterior fixation in an experimental unstable burst fracture model. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(3):216-224. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0b013e31807a2f61

28. Li Z, Liu H, Yang M, Zhang W. A biomechanical analysis of four anterior cervical techniques to treating multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a finite element study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):278. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04150-7

29. Calek AK, Cornaz F, Suter M, Fasser MR, Baumgartner S, Sager P, et al. Load distribution on intervertebral cages with and without posterior instrumentation. Spine J. 2024;24(5):889-898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2023.10.017

30. Sharif S, Shaikh Y, Yaman O, Zileli M. Surgical Techniques for Thoracolumbar Spine Fractures: WFNS Spine Committee Recommendations. Neurospine. 2021;18(4):667-680. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2142206.253

31. Avanzi O, Meves R, Silber Caffaro MF, Buarque de Hollanda JP, Queiroz M. Thoracolumbar Burst Fractures: Correlation between Kyphosis and Function Post Non-Operative Treatment. Rev Bras Ortop. 2009;44(5):408-414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30271-8

32. Le Huec JC, Thompson W, Mohsinaly Y, Barrey C, Faundez A. Sagittal balance of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2019;28(9):1889-1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06083-1

33. Hira K, Nagata K, Hashizume H, Asai Y, Oka H, Tsutsui S, et al. Relationship of sagittal spinal alignment with low back pain and physical performance in the general population. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20604. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00116-w

34. McLain RF. The biomechanics of long versus short fixation for thoracolumbar spine fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(11 Suppl):S70-79; discussion S104. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000218221.47230.dd

35. Iwata S, Kotani T, Sakuma T, Iijima Y, Okuwaki S, Ohyama S, et al. Risk Factors for Cage Subsidence in Minimally Invasive Lateral Corpectomy for Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures. Spine surgery and related research. 2023;7(4):356-362. https://doi.org/10.22603/ssrr.2022-0215

36. Farley CW, Curt BA, Pettigrew DB, Holtz JR, Dollin N, Kuntz Ct. Spinal cord intramedullary pressure in thoracic kyphotic deformity: a cadaveric study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(4):E224-230. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822dd69b

37. Sanderson PL, Fraser RD, Hall DJ, Cain CM, Osti OL, Potter GR. Short segment fixation of thoracolumbar burst fractures without fusion. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(6):495-500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005860050212

38. Tisot RA, Vieira JdS, Santos RTd, Badotti AA, Collares DdS, Stumm LD, et al. Burst fracture of the thoracolumbar spine: correlation between kyphosis and clinical result of the treatment. Coluna/Columna. 2015;14(2):129-133. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1808-185120151402146349

39. Su YF, Tsai TH, Lieu AS, Lin CL, Chang CH, Tsai CY, Su HY. Bone-Mounted Robotic System in Minimally Invasive Spinal Surgery for Osteoporosis Patients: Clinical and Radiological Outcomes. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:589-599. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S359538

40. Orosz LD, Schuler KA, Allen BJ, Lerebo WT, Yamout T, Roy RT, et al. Performance comparison between Hounsfield units and DXA in predicting lumbar cage subsidence in the degenerative population. Spine J. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2025.03.028