Original article

Ukrainian Neurosurgical Journal. 2025;31(3):30-36

https://doi.org/10.25305/unj.328642

1 Laboratory of Neurophysiology, Immunology and Biochemistry, State Institution «P. V. Voloshyn Institute of Neurology, Psychiatry and Narcology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine», Kharkiv, Ukraine

2 Department of Functional Neurosurgery with a Group of Pathomorphology, State Institution «P. V. Voloshyn Institute of Neurology, Psychiatry and Narcology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine», Kharkiv, Ukraine

Received: 06 May 2025

Accepted: 26 May 2025

Address for correspondence:

Valentina V. Geiko, Laboratory of Neurophysiology, Immunology and Biochemistry, State Institution «P. V. Voloshyn Institute of Neurology, Psychiatry and Narcology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine», 46 Academician Pavlova St., Kharkiv, Ukraine, 61068; e-mail: vvgeiko@gmail.com

Aim: To investigate the levels of inflammatory mediators of the immune system in blood serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in combatants with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) at different time periods after its acquisition.

Materials and methods: IL-6, TNFα, IL-10 and TGFβ1 concentrations were measured according to the instructions of the «Human ELISA Kit» (Elabscience Bionovation Inc., USA) in 53 paired serum and CSF samples from patients with combat mTBI.

Results: In the general group of patients with mTBI, a significant increase in the peripheral content of IL-6, IL-10, TGFβ1 was found, compared with healthy donors (control). When studying these indicators depending on the duration of the post-traumatic period, a persistent increase in the level of IL-6 was shown in combination with significantly increased TGFβ1 concentration indicators and a tendency to an increased level of IL-10. At the same time, the analysis of the central content of inflammatory biomarkers did not reveal their significant changes at different times after TBI, with the exception of a tendency to a decrease in the presence of IL-6, the presence of which in paired analytes prevailed in CSF along with the prevalence of peripheral finding of TNFα, IL-10, TGFβ1.

Conclusions: Thus, the increased content of circulating pro-inflammatory IL-6 and TNFα in the intermediate and remote periods of the course of TBI and a significantly (approximately 6 times) increased level of pleiotropic TGFβ1 in combination with anti-inflammatory IL-10 indicate the persistent nature of inflammation, which indicates the possibility of induction of neurodegenerative processes in combatants with TBI. Such results confirm the feasibility of comprehensive monitoring of immunological markers of inflammation to identify potential directions for adequate pathogenetic therapy even in the context of significantly distant consequences of TBI.

Keywords: combat mild TBI; inflammatory markers of the immune system; time periods of TBI

Introduction

Traumatic brain injuries, which are widespread among young people, are often a factor in the development of long-term neurological deficits, cognitive impairments, and emotional disorders. These consequences pose important medical and socio-economic challenges associated with high mortality and disability of patients, as well as with the triggering value of post-traumatic neuroinflammation in the occurrence of neurodegenerative processes, which subsequently lead to an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, etc. [1–7]. Currently, TBI is a global health problem worldwide, exacerbated by inadequate monitoring and the lack of effective diagnostic methods and pathogenetic treatment at various stages of the post-traumatic period, which can cause complications of the disease due to the initiation of complex biochemical cascades and immunological processes leading to secondary neuroinflammation [8–12].

Moreover, the issue of TBI-related consequences is becoming increasingly urgent in the context of a full-scale war of aggression in Ukraine with a violation of the world charter of the sovereignty of democratic states due to the Russian invasion. This applies both to direct participants in hostilities using modern destructive weapons, and to the civilian population, which is permanently exposed to stochastic terrorist bombing.

In the overall structure of brain injuries, mine-explosive injuries are detected in 70% of victims, and at least 80% of them are diagnosed as mild injuries [13, 14]. The most common type of mTBI among military personnel is concussion and mild brain contusion, and such injuries, most often caused by an explosion, are considered “signature wounds” of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan [15–18]. Currently, there are quite limited objective indicators for identifying individuals with a high risk of developing neuropsychiatric disorders and adverse consequences and complications [18], in particular, among military personnel and veterans of modern wars against the background of the staggering spread of TBI [19].

It is known that TBI is accompanied by an immediate immune system response. Innate immunity helps to reduce the progression of pathogens by activating the healing processes and remodeling of nerve tissue damage while also preparing the body for an adaptive immune response, which is based on the activation of T and B lymphocytes, the excess of which has the ability to stimulate neuroinflammation [11]. Previous studies have documented a reversible increase in the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNFα and IL-10 within 24 hours after the explosion during training [20], and as a result of the acute phase reaction in combatants with severe TBI [21]. The cytokines promote the induction of the first phase of inflammation, which is aimed at neuroprotection and restoration of homeostasis and nervous tissue integrity [22, 23].

Accordingly, the study of neuroinflammation and its associated immune biomarkers is of growing importance [23, 24]. Evidence suggests that uncontrolled or insufficiently effective regulation of the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory activity of mediators of the immunological response may be the cause of the formation of long-term symptoms of CNS damage due to TBI [25–28] with the development of autoimmune processes and the subsequent formation of neurodegenerative pathology.

It is noteworthy that most of the literature on the pathogenesis of neuroinflammation focuses on studying the mechanisms of its development, which are activated in patients with severe TBI in the most acute period (the first hours, days, weeks) [14, 21, 29, 30]. At the same time, studies of immunological markers in the chronic course of combat mTBI are not sufficiently presented.

Taking this into account, the aim of the work was to study the levels of inflammatory mediators of the immune system in the serum and CSF in combatants with mTBI at different time periods after its acquisition.

Materials and methods

Study participants

The study was performed using 53 paired serum and CSF samples obtained from male patients aged 36.03±1.40 years, who were treated in the neurosurgical department of the P. V. Voloshyn Institute of Neurology, Psychiatry and Narcology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine during 2024 years.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who suffered mTBI in the form of concussion and mild brain contusion during active hostilities in Ukraine.

Exclusion criteria

Severe TBI, the presence of multiple trauma and chronic somatic diseases.

Group characteristics

Depending on the duration of the post-traumatic period, the combatants were divided into three groups: I (acute period) – 1.22±0.19 months; II (interim period) – 6.39±0.74 months; III (remote period) – 13.43±1.13 months. The control group, limited to serum samples only for ethical and medical reasons, consisted of 8 practically healthy male donors aged 37.38±2.40 years. All patients with TBI, regardless of the time after its acquisition, were included in the general comparison group – TBI.

Study design

Peripheral blood with a volume of up to 8 ml was obtained by puncture from the cubital vein with subsequent centrifugation (4000 revolutions per minute, within 10 minutes), serum collection (120 μl into separate Eppendorf tubes) and storage at -80°C until quantitative ELISA.

CSF samples were obtained with patient consent during neurosurgical intervention by lumbar puncture with subsequent storage of the required number of its samples (120 μl) at -80°C. The process from serum and CSF sample collection to storage lasted no more than 3 hours. Serum and CSF samples were used with one freeze-thaw cycle.

The concentrations of immune system mediators were measured spectrophotometrically with recording of values on a microplate enzyme immunoassay analyzer GBG Stat Fax 2010 (USA) with a wavelength of 450 nm according to the instructions and protocols of the manufacturer of «Human ELISA Kit» from «Elabscience Bionovation Inc.» (USA), «…which are used for their determination in blood serum and other biological fluids of the body (plasma, CSF, tissue homogenates, supernatants of cell structures, etc.)». The concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα and anti-inflammatory IL-10 and TGFβ1 were determined. The sensitivity of the analyses was: IL-6 – 0.94 pg/ml, IL-10 – 0.94 pg/ml, TNFα – 4.69 pg/ml, TGFβ1 – 18.75 pg/ml; detection range: IL-6 – 1.56–100 pg/ml, IL-10 – 1.56–100 pg/ml, TNFα – 7.81–500 pg/ml, TGFβ1 – 31.25–2000 pg/ml. Since the «Human ELISA Kit» is intended for research purposes only and cannot be used for clinical diagnosis or any other related procedures, reference values for cytokine levels in peripheral blood and CSF are not provided in this test system.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was performed using the Microsoft Office Excel program using Student's t-test to assess differences between comparison groups.

Results

Determination of concentrations of inflammatory mediators of the immune system in the generalized group of patients with combat TBI revealed a significant increase, compared with controls, in the peripheral content of pro-inflammatory IL-6, anti-inflammatory IL-10 and TGFβ1 (Table 1). When studying these indicators depending on the duration of the post-traumatic period, it was shown that the increased level of IL-6 production was preserved in combination with significantly increased, relative to healthy donors, serum TGFβ1 concentrations and a tendency to an increased level of IL-10 at all stages of the course of TBI.

Table 1. Levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the serum and CSF in patients with combat mTBI at different periods after its receipt

|

Cytokines |

Analytes |

Groups |

||||

|

Control |

mTBI |

I (acute period, 1.22±0.19 months) |

II (interim period, 6.39±0.74 months) |

III (remote period, 13.43±1.13 months) |

||

|

IL-6 |

serum |

0.20±0.03 |

0.30±0.04** |

0.32±0.05** |

0.26±0.05 |

0.32±0.07 |

|

CSF |

― |

1.06±0.19 |

1.68±0.54 |

0.81±0.09# |

0.76±0.16# |

|

|

IL-10 |

serum |

0.04±0.01 |

0.38±0.14*** |

0.35±0.26 |

0.46±0.24* |

0.34±0.26 |

|

CSF |

― |

0.19±0.04 |

0.27±0.10 |

0.14±0.05 |

0.14±0.05 |

|

|

TNFα |

serum |

15.93±3.54 |

65.04±31.02* |

5.37±3.01** |

51.39±26.45# |

149.44±94.40 |

|

CSF |

― |

6.95±0.85 |

6.00±1.36 |

5.94±1.00 |

9.17±1.91 |

|

|

TGFβ1 |

serum |

242.80±81.70 |

1374.78±230.13***** |

1471.90±41.11**** |

1450.50±447.80*** |

1179.50±345.80*** |

|

CSF |

― |

88.31±12.78 |

82.30±16.10 |

104.70±30.60 |

77.60±18.10 |

|

Notes. * p ≤ 0.1; ** p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.02; **** p ≤ 0.01; ***** p ≤ 0.001: compared to control; # p ≤ 0.1: compared to group I

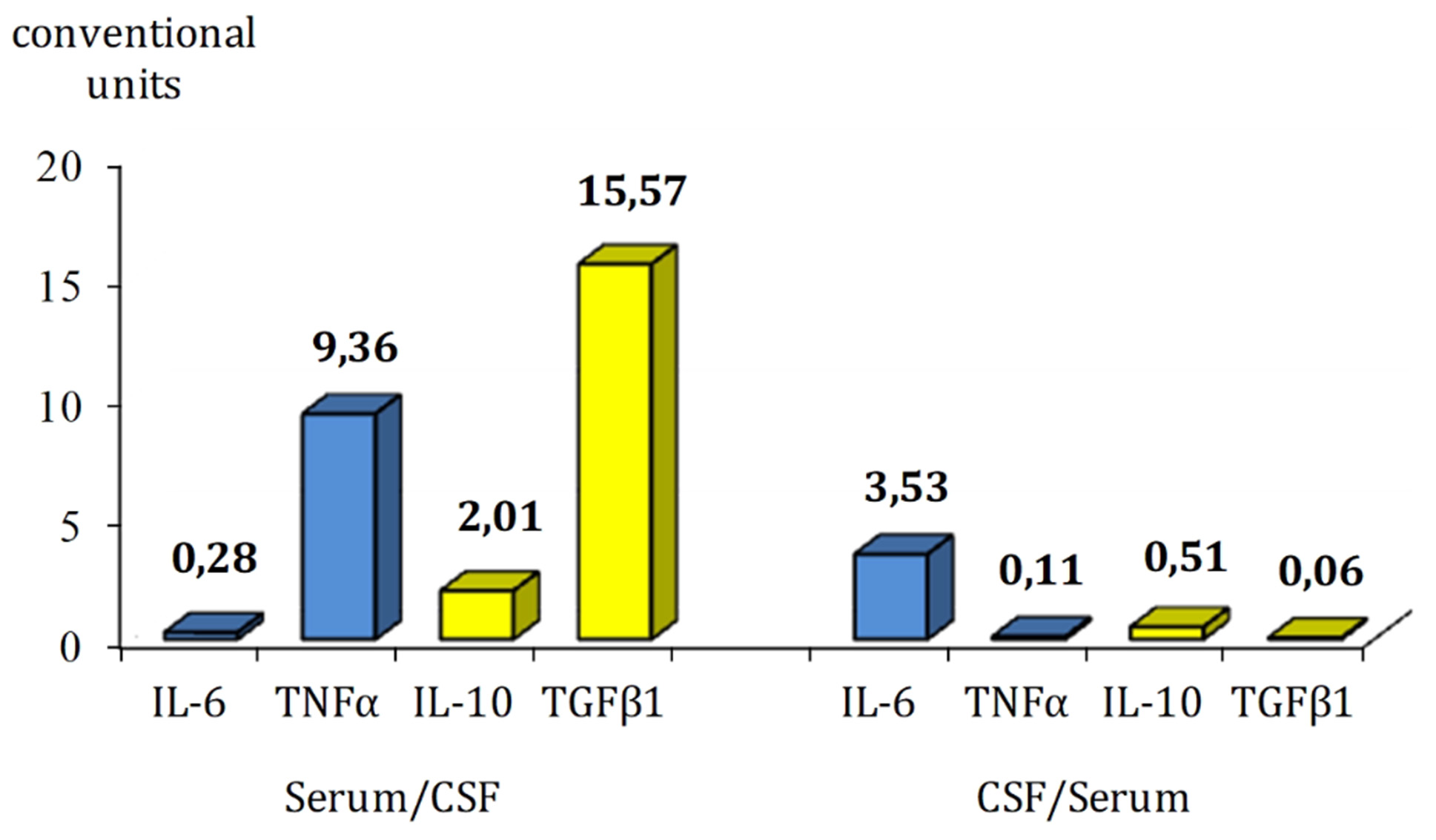

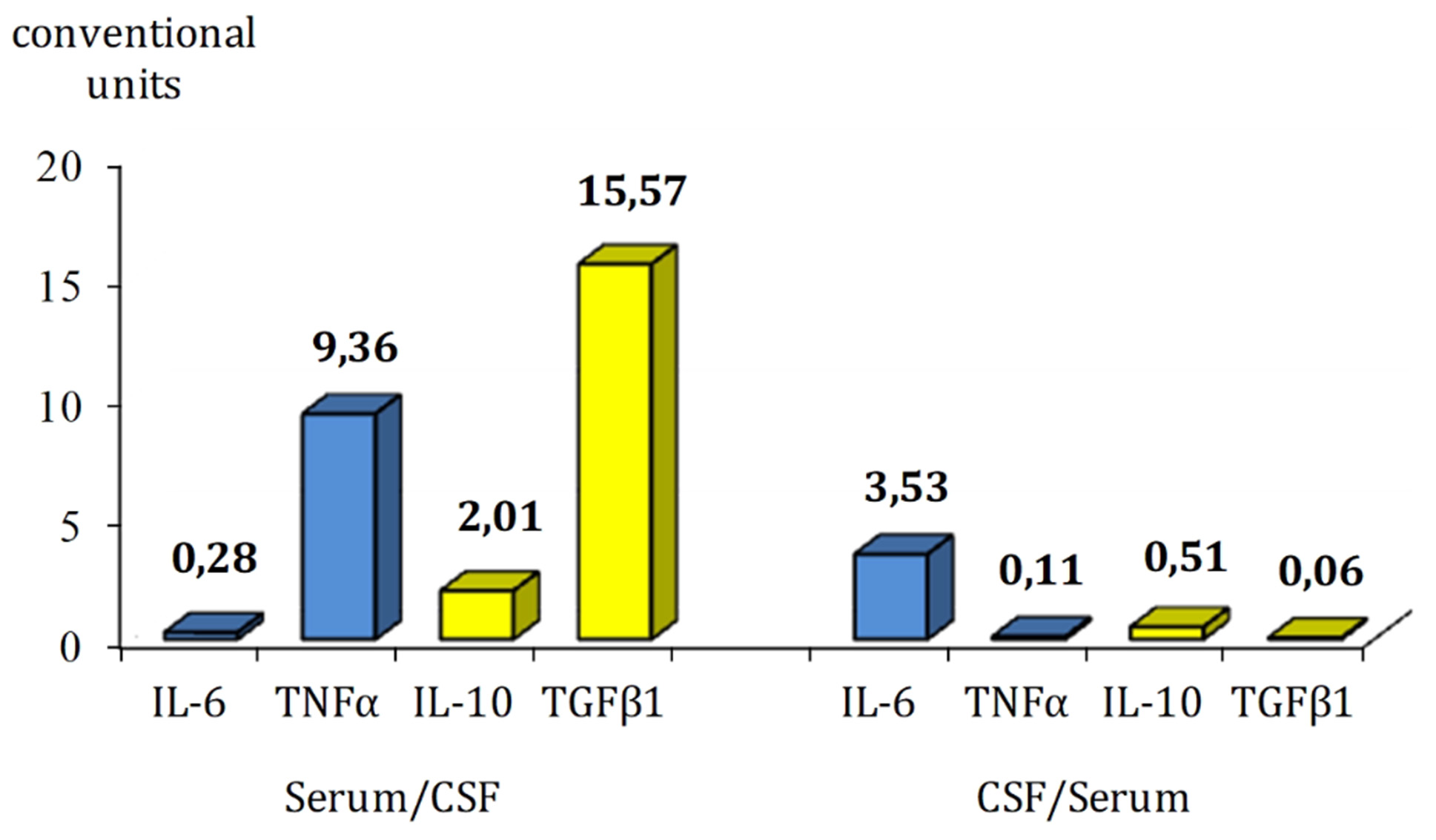

At the same time, analysis of the content of inflammatory markers in CSF did not reveal significant differences at different times after TBI, with the exception of a tendency to decrease the concentration of IL-6 depending on the increase in the duration of the post-traumatic period. When comparing the ratio of peripheral and central inflammatory cytokine content in paired biological analytes, it was found that in the process of chronicity of TBI consequences in combatants, only the content of IL-6 prevails in CSF along with the prevalence of peripheral TNFα, IL-10 and TGFβ1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Relation between peripheral and central inflammatory cytokine levels in the serum and CSF in patients with combat TBI

The obtained results do not contradict the literature data on the content of immune system mediators in patients with TBI, taking into account the severity and time periods of its course. Thus, when studying the concentrations of IL-6, IL10, TNFα, TGFβ1, their multidirectional correlation was revealed with a particularly significant (28 times) predominance of IL-6 content in CSF compared to serum, which demonstrated its important role in the initiation of the acute phase [21, 30], and in our study, the quantitative features of the representation of inflammatory cytokines in the brain and blood reflect the consequences of chronic neuroinflammation.

Conclusion

The moderately elevated serum IL-6 level is consistent with the idea that it can escape from the injured brain into the bloodstream. It is believed that this is the main mechanism for activating peripheral metabolism, endocrine and immune responses, i.e., its production in the periphery is stimulated [31] with simultaneous induction of the synthesis of anti-inflammatory IL-10 and TGFβ1 to provide a regulatory immunosuppressive effect [30]. This likely demonstrates a physiological normalization of the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines as a mechanism for restraining the intensity of the secondary phase of neuroinflammation, which in the process of chronic mTBI is aimed at slowing down or preventing complications, which in the case of uncontrolled hyperadaptive immune response leads to “secondary injury”, which can contribute to further strengthening of neuropsychiatric symptoms in much later periods.

Given that IL-6 plays a key role in both the acute and chronic phase of the response, and persistent neuroinflammation is associated with a poor prognosis [26, 32], our long-term findings after mTBI suggest the persistence of chronic inflammatory processes with a predominance of their activity in the periphery. This likely reflects the consequences of secondary neuroinflammation with changes in systemic immunity, which may be associated with disruption of the vascular network of the CNS barrier structures, leading to the leakage of detritus (a product of tissue breakdown) and inflammatory mediators with the development of complications such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [11, 33–35], which in turn may complicate the consequences of the primary injury and local inflammatory reaction. According to the increase in the post-traumatic period, the body compensates for SIRS by increasing the peripheral level of inflammatory mediators, which, along with the activation of anti-inflammatory cytokines, contributes to the normalization of their balance and outlines directions for selective immunomodulatory therapeutic interventions at much later stages of the course of TBI.

In the context of the current study, the results obtained are organically combined with the literature and our previous data on the features of immune reactivity at different times after mTBI in combatants, which indicate chronic inflammation in the remote periods of its course, which is capable of initiating the formation of autoimmune processes with subsequent induction of neurodegenerative pathology. This concerns the increase in serum concentrations of immunoglobulins of the main classes, especially IgG, which reflected the formation and long-term maintenance of the humoral component of adaptive immunity in the remote periods of mTBI, as well as the modulation of the eliminating (detoxification) function of the immune system in the form of an increase in the number of small, most pathogenic, soluble antigen-antibody complexes along with the suppression of the formation of large and medium-sized conglomerates that stimulate the activity of micro- and macrophage systems of nonspecific natural resistance of the organism [36]. In addition, a slight increase in the content of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα in the intermediate and long-term observation periods, along with a significantly (approximately 6 times) increased level of pleiotropic TGFβ1 in serum, confirms the persistent character of inflammation, which does not exclude its role in stimulating neurodegenerative processes in patients with mTBI.

It is known that activation of TGFβ1 production can be a consequence of both beneficial and harmful effects of neuroinflammation in order to suppress proinflammatory reactions and enhance tissue repair of reactive astrocytes and microglia [37]. Astrocytes are the main source of endogenous TGFβ1 production in the CNS, providing metabolic and structural support for neurons and participating in the regulation of brain homeostasis, synaptic plasticity and blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity [38–40]. In addition, astrocytes play a crucial role in responses to the pathological effects of disease and brain injury [38–42]. TGFβ, among other inflammatory cytokines, is a key regulator and signaling factor in the transformation of normal astrocytes into reactive phenotypes [40, 43, 44]. As TGFβ1 is a pleiotropic cytokine, its excess may contribute to neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment in TBI [45–47], as well as to the inhibition of microglial proliferation, astrocyte activity, and glial scar formation [41, 43, 48]. Reactive astrogliosis is thought to be a protective mechanism aimed at limiting damage, controlling inflammation, and restoring homeostasis [38, 49, 50]. However, like peripheral inflammation, astrogliosis can become maladaptive and contribute to secondary damage to neural tissues [51]. As a result of studying these aspects of reactivity, neurotoxic (A1) and neuroprotective (A2) astrocytes have been identified [52]. The importance of considering the context-dependent modulation of their reactivity by TGFβ1 signaling is emphasized. It is noteworthy that TGFβ1 promotes the development of macrophages and their polarization into an M-2-like pool, which is associated with neuroprotection, migration, and angiogenesis [53].

Thus, when studying the content of inflammatory mediators of the immune response in patients with combat mTBI, a total increase in their level in the peripheral blood serum was found, which corresponds to the literature data on the important role of the immune system in the course of TBI and the formation of its long-term consequences and complications [26, 29, 33, 54]. Modern scientific studies have obtained numerous data indicating the global role of the immune system both in the mechanisms of acute response and in the chronic course of TBI, which emphasizes the need to modulate neuroinflammation in the process of forming secondary trauma due to its uncontrolled development. At the same time, there is a lack of consensus on the methodology of TBI research in connection with the measurement of inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood, which does not provide accurate differentiation of the causes of inflammation in patients who suffer multiple trauma during combat operations [32]. In view of this, studies of both peripheral and central content of immune response mediators are of particular importance, which is one of the virtues of this work.

Thus, the results of our study indicate the feasibility of comprehensive monitoring of central and peripheral inflammatory cytokine content to determine potential directions of adequate pathogenetic therapy even in conditions of significantly distant consequences of mTBI in order to substantiate the possibility of returning servicemen to direct participation in combat operations, which is extremely relevant during war.

Against the background of the high modernity of the actual study, which was carried out using biological materials from participants and veterans of active hostilities in Ukraine, unfortunately, a certain drawback can be noted in the form of a relatively small size of the comparison groups and a limited spectrum of inflammatory cytokines, and the inability of determining neurotrophic factors (BDNF, VEGF, PDGF) in order to study the mechanisms of neuroplasticity in the process of structural and functional recovery of the CNS in patients with TBI. This is objectively related to limited funding for scientific research in a medical institution under the conditions of Russia's full-scale aggressive attack on Ukraine.

In the direction of future research, it seems appropriate to include clinical and immunological comparisons of the course of TBI, taking into account the neurosurgical treatment of comorbid pathology associated with mechanical damage during combat TBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to laboratory assistant Olha Kyrychenko for her impeccable contribution in the receipt, preparation, and storage of biological analytes, as well as in their systematization according to the research objectives and in the technical support of ELISA analysis, the preparation of the manuscript with constant stimulation and discussion of the work.

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The work was carried out in accordance with the main provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association on the ethical principles of conducting scientific research involving human subjects, the Council of Europe Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of the SI «P. V. Voloshyn Institute of Neurology, Psychiatry and Narcology of the NAMS of Ukraine», which did not reveal any violations of ethical or legal standards during the study (Minutes No.12-a dated 27.12.2024).

Informed consent

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Funding

Not applicable.

References

1. Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2013 Jan;136(Pt 1):28-42. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws322

2. Aungst SL, Kabadi SV, Thompson SM, Stoica BA, Faden AI. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury causes chronic neuroinflammation, changes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, and associated cognitive deficits. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014 Jul;34(7):1223-32. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2014.75

3. Bloom GS. Amyloid-β and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014 Apr;71(4):505-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847

4. Blennow K, Brody DL, Kochanek PM, Levin H, McKee A, Ribbers GM, Yaffe K, Zetterberg H. Traumatic brain injuries. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016 Nov 17;2:16084. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.84

5. Reams N, Eckner JT, Almeida AA, Aagesen AL, Giordani B, Paulson H, Lorincz MT, Kutcher JS. A Clinical Approach to the Diagnosis of Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Jun 1;73(6):743-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.5015

6. Mendez MF. What is the Relationship of Traumatic Brain Injury to Dementia? J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(3):667-681. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-161002

7. Raza Z, Hussain SF, Ftouni S, Spitz G, Caplin N, Foster RG, Gomes RSM. Dementia in military and veteran populations: a review of risk factors-traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, deployment, and sleep. Mil Med Res. 2021 Oct 13;8(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00346-z

8. Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Status of Potential Mechanisms of Injury and Neurological Outcomes. J Neurotrauma. 2015 Dec 1;32(23):1834-48. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2014.3352

9. Anthonymuthu TS, Kenny EM, Bayır H. Therapies targeting lipid peroxidation in traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2016 Jun 1;1640(Pt A):57-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.006

10. Dorsett CR, McGuire JL, DePasquale EA, Gardner AE, Floyd CL, McCullumsmith RE. Glutamate Neurotransmission in Rodent Models of Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017 Jan 15;34(2):263-272. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.4373

11. Jassam YN, Izzy S, Whalen M, McGavern DB, El Khoury J. Neuroimmunology of Traumatic Brain Injury: Time for a Paradigm Shift. Neuron. 2017 Sep 13;95(6):1246-1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.010

12. Simon DW, McGeachy MJ, Bayır H, Clark RS, Loane DJ, Kochanek PM. The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017 Mar;13(3):171-191. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.13. Erratum in: Nat Rev Neurol. 2017 Sep;13(9):572. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.116

13. Booker J, Sinha S, Choudhari K, Dawson J, Singh R. Predicting functional recovery after mild traumatic brain injury: the SHEFBIT cohort. Brain Inj. 2019;33(9):1158-1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1629626

14. Edwards KA, Gill JM, Pattinson CL, Lai C, Brière M, Rogers NJ, Milhorn D, Elliot J, Carr W. Interleukin-6 is associated with acute concussion in military combat personnel. BMC Neurol. 2020 May 25;20(1):209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01760-x

15. Yamamoto EA, Koike S, Luther M, Dennis L, Lim MM, Raskind M, Pagulayan K, Iliff J, Peskind E, Piantino JA. Perivascular Space Burden and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in US Veterans With Blast-Related Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2024 Jul;41(13-14):1565-1577. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2023.0505

16. Wojcik BE, Stein CR, Bagg K, Humphrey RJ, Orosco J. Traumatic brain injury hospitalizations of U.S. army soldiers deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Jan;38(1 Suppl):S108-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.006

17. Boyle E, Cancelliere C, Hartvigsen J, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD. Systematic review of prognosis after mild traumatic brain injury in the military: results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Mar;95(3 Suppl):S230-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.297

18. Kong LZ, Zhang RL, Hu SH, Lai JB. Military traumatic brain injury: a challenge straddling neurology and psychiatry. Mil Med Res. 2022 Jan 6;9(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00363-y

19. McDonald SJ, O'Brien TJ, Shultz SR. Biomarkers add value to traumatic brain injury prognosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Sep;21(9):761-763. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00306-4

20. Rodney T, Taylor P, Dunbar K, Perrin N, Lai C, Roy M, Gill J. High IL-6 in military personnel relates to multiple traumatic brain injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2020 Aug 17;392:112715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112715

21. Kossmann T, Hans VH, Imhof HG, Stocker R, Grob P, Trentz O, Morganti-Kossmann C. Intrathecal and serum interleukin-6 and the acute-phase response in patients with severe traumatic brain injuries. Shock. 1995 Nov;4(5):311-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00024382-199511000-00001

22. Hinson HE, Rowell S, Schreiber M. Clinical evidence of inflammation driving secondary brain injury: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Jan;78(1):184-91. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000468

23. Hernandez-Ontiveros DG, Tajiri N, Acosta S, Giunta B, Tan J, Borlongan CV. Microglia activation as a biomarker for traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2013 Mar 26;4:30. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2013.00030

24. McKee CA, Lukens JR. Emerging Roles for the Immune System in Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Immunol. 2016 Dec 5;7:556. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00556

25. Ramlackhansingh AF, Brooks DJ, Greenwood RJ, Bose SK, Turkheimer FE, Kinnunen KM, Gentleman S, Heckemann RA, Gunanayagam K, Gelosa G, Sharp DJ. Inflammation after trauma: microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2011 Sep;70(3):374-83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22455

26. Gerber KS, Alvarez G, Alamian A, Behar-Zusman V, Downs CA. Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation in Traumatic Brain Injury. Clin Nurs Res. 2022 Sep;31(7):1203-1218. https://doi.org/10.1177/10547738221107081

27. Puntambekar SS, Saber M, Lamb BT, Kokiko-Cochran ON. Cellular players that shape evolving pathology and neurodegeneration following traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2018 Jul;71:9-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.03.033

28. Needham EJ, Helmy A, Zanier ER, Jones JL, Coles AJ, Menon DK. The immunological response to traumatic brain injury. J Neuroimmunol. 2019 Jul 15;332:112-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.04.005

29. Yue JK, Kobeissy FH, Jain S, Sun X, Phelps RRL, Korley FK, Gardner RC, Ferguson AR, Huie JR, Schneider ALC, Yang Z, Xu H, Lynch CE, Deng H, Rabinowitz M, Vassar MJ, Taylor SR, Mukherjee P, Yuh EL, Markowitz AJ, Puccio AM, Okonkwo DO, Diaz-Arrastia R, Manley GT, Wang KKW. Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers for Traumatic Brain Injury Diagnosis and Prognosis: A TRACK-TBI Pilot Study. Neurotrauma Rep. 2023 Mar 24;4(1):171-183. https://doi.org/10.1089/neur.2022.0060

30. Csuka E, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Lenzlinger PM, Joller H, Trentz O, Kossmann T. IL-10 levels in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: relationship to IL-6, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1 and blood-brain barrier function. J Neuroimmunol. 1999 Nov 15;101(2):211-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00148-4

31. Terreni L, De Simoni MG. Role of the brain in interleukin-6 modulation. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1998 May-Aug;5(3-4):214-9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000026339

32. Malik S, Alnaji O, Malik M, Gambale T, Farrokhyar F, Rathbone MP. Inflammatory cytokines associated with mild traumatic brain injury and clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2023 May 12;14:1123407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1123407

33. Lu J, Goh SJ, Tng PY, Deng YY, Ling EA, Moochhala S. Systemic inflammatory response following acute traumatic brain injury. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2009 Jan 1;14(10):3795-813. https://doi.org/10.2741/3489

34. Plog BA, Dashnaw ML, Hitomi E, Peng W, Liao Y, Lou N, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Biomarkers of traumatic injury are transported from brain to blood via the glymphatic system. J Neurosci. 2015 Jan 14;35(2):518-26. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3742-14.2015

35. Weaver LC, Bao F, Dekaban GA, Hryciw T, Shultz SR, Cain DP, Brown A. CD11d integrin blockade reduces the systemic inflammatory response syndrome after traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2015 Sep;271:409-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.07.003

36. Geiko VV, Posokhov MF, Lemondzhava ZM. Features of immunological reactivity of patients with combat traumatic brain injury depending on its type and chronicity. Ukr Bull Psychoneurol. 2025;33,1(122):13-8. https://doi.org/10.36927/2079-0325-V33-is1-2025-2

37. Luo J. TGF-β as a Key Modulator of Astrocyte Reactivity: Disease Relevance and Therapeutic Implications. Biomedicines. 2022 May 23;10(5):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10051206

38. Sofroniew MV. Astrocyte Reactivity: Subtypes, States, and Functions in CNS Innate Immunity. Trends Immunol. 2020 Sep;41(9):758-770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2020.07.004

39. Escartin C, Galea E, Lakatos A, O'Callaghan JP, Petzold GC, Serrano-Pozo A, Steinhäuser C, Volterra A, Carmignoto G, Agarwal A, Allen NJ, Araque A, Barbeito L, Barzilai A, Bergles DE, Bonvento G, Butt AM, Chen WT, Cohen-Salmon M, Cunningham C, Deneen B, De Strooper B, Díaz-Castro B, Farina C, Freeman M, Gallo V, Goldman JE, Goldman SA, Götz M, Gutiérrez A, Haydon PG, Heiland DH, Hol EM, Holt MG, Iino M, Kastanenka KV, Kettenmann H, Khakh BS, Koizumi S, Lee CJ, Liddelow SA, MacVicar BA, Magistretti P, Messing A, Mishra A, Molofsky AV, Murai KK, Norris CM, Okada S, Oliet SHR, Oliveira JF, Panatier A, Parpura V, Pekna M, Pekny M, Pellerin L, Perea G, Pérez-Nievas BG, Pfrieger FW, Poskanzer KE, Quintana FJ, Ransohoff RM, Riquelme-Perez M, Robel S, Rose CR, Rothstein JD, Rouach N, Rowitch DH, Semyanov A, Sirko S, Sontheimer H, Swanson RA, Vitorica J, Wanner IB, Wood LB, Wu J, Zheng B, Zimmer ER, Zorec R, Sofroniew MV, Verkhratsky A. Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat Neurosci. 2021 Mar;24(3):312-325. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00783-4

40. Lee HG, Wheeler MA, Quintana FJ. Function and therapeutic value of astrocytes in neurological diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022 May;21(5):339-358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00390-x

41. Giovannoni F, Quintana FJ. The Role of Astrocytes in CNS Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2020 Sep;41(9):805-819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2020.07.007

42. Linnerbauer M, Wheeler MA, Quintana FJ. Astrocyte Crosstalk in CNS Inflammation. Neuron. 2020 Nov 25;108(4):608-622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.012

43. Colombo E, Farina C. Astrocytes: Key Regulators of Neuroinflammation. Trends Immunol. 2016 Sep;37(9):608-620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2016.06.006

44. Price BR, Johnson LA, Norris CM. Reactive astrocytes: The nexus of pathological and clinical hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Jul;68:101335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101335

45. Patel RK, Prasad N, Kuwar R, Haldar D, Muneer PMA. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling regulates neuroinflammation and apoptosis in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2017 Aug;64:244-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.012

46. Diniz LP, Matias I, Siqueira M, Stipursky J, Gomes FCA. Astrocytes and the TGF-β1 Pathway in the Healthy and Diseased Brain: a Double-Edged Sword. Mol Neurobiol. 2019 Jul;56(7):4653-4679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1396-y

47. Kandasamy M, Anusuyadevi M, Aigner KM, Unger MS, Kniewallner KM, de Sousa DMB, Altendorfer B, Mrowetz H, Bogdahn U, Aigner L. TGF-β Signaling: A Therapeutic Target to Reinstate Regenerative Plasticity in Vascular Dementia? Aging Dis. 2020 Jul 23;11(4):828-850. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2020.0222

48. Koyama Y. Signaling molecules regulating phenotypic conversions of astrocytes and glial scar formation in damaged nerve tissues. Neurochem Int. 2014 Dec;78:35-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2014.08.005

49. Arranz AM, De Strooper B. The role of astroglia in Alzheimer's disease: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2019 Apr;18(4):406-414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30490-3

50. Pekny M, Pekna M. Astrocyte reactivity and reactive astrogliosis: costs and benefits. Physiol Rev. 2014 Oct;94(4):1077-98. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2013

51. McConnell HL, Li Z, Woltjer RL, Mishra A. Astrocyte dysfunction and neurovascular impairment in neurological disorders: Correlation or causation? Neurochem Int. 2019 Sep;128:70-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2019.04.005

52. Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, Bennett ML, Münch AE, Chung WS, Peterson TC, Wilton DK, Frouin A, Napier BA, Panicker N, Kumar M, Buckwalter MS, Rowitch DH, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Stevens B, Barres BA. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature. 2017 Jan 26;541(7638):481-487. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21029

53. Li Z, Xiao J, Xu X, Li W, Zhong R, Qi L, Chen J, Cui G, Wang S, Zheng Y, Qiu Y, Li S, Zhou X, Lu Y, Lyu J, Zhou B, Zhou J, Jing N, Wei B, Hu J, Wang H. M-CSF, IL-6, and TGF-β promote generation of a new subset of tissue repair macrophage for traumatic brain injury recovery. Sci Adv. 2021 Mar 12;7(11):eabb6260. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb6260

54. Bouras M, Asehnoune K, Roquilly A. Immune modulation after traumatic brain injury. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Dec 1;9:995044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.995044