Original article

Ukrainian Neurosurgical Journal. 2025;31(2):44-54

https://doi.org/10.25305/unj.323331

1 Department of Neurosurgery, Command Hospital Western Command, Chandimandir, India

2 Best Superspeciality Hospital, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India

3 Department of Neurosurgery, Command Hospital Eastern Command, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

4 Department of Neurosurgery, Command Hospital Northern Command, Udhampur, Jammu and Kashmir, India

5 Department of Neurosurgery, NIMS University, Jaipur, India

Received: 20 February 2025

Accepted: 19 March 2025

Address for correspondence:

Chinmaya Srivastava, Department of Neurosurgery, Command Hospital Eastern Command, I17/1E, Alipore Rd, Alipore Police Line, Alipore, Kolkata, West Bengal, 700027, India, e-mail: chinmayas4@gmail.com

Introduction: Gamma Knife radiosurgery (GKRS) provides in general a high dose ionizing radiation to specific target location, which has already been defined by stereotaxy for the treatment.

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are one such indication for GKRS they are rare, occurring at an incidence of 15-18 cases per 100,000 adults, with a rupture rate of 2–4%. GKRS is indicated for small (< 3.5 cm), surgically high-risk, deep-seated and complex AVMs. Successful AVM treatment in GKRS eliminates the risk of intracranial haemorrhage, complete nidal obliteration, limiting the development of new deficit from radiation-induced changes.

Materials and Methods: This study was conducted in the Department of Neurosurgery, a tertiary care center , New Delhi for the duration of two years (September 2019 to September 2021). A total of 40 patients (N) were studied. Variables included demographic profile, clinical profile, AVM grading, radiation dose and treatment outcomes particularly nidal obliteration and symptom resolution. The factors which affected obliteration of AVM and six-monthly follow-up were analysed.

Results: The study showed among all variables that the initial volume of nidus, duration following GKRS were important predictors for AVM obliteration with statistically significant p-values (<0.05).

Conclusion: GKRS is effective treatment modality in AVMs, especially those with low nidus volume, low Spetzler-Martin (SM) grade, deep venous drainage, young age and deep-seated lesions. However, in this study, the p-values were not statistically significant (p-value >0.05) for above parameters. Among all, the initial nidus volume, and the duration of post GKRS for the obliteration of AVM had significant p-values (<0.05).

Key words: arteriovenous malformations; nidus volume; Gamma Knife Radiosurgery

Introduction

Gamma Knife radio surgery (GKRS) delivers in general high dose ionizing radiation to specific target location, which has already been defined by stereotaxy for the treatment [1]. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are one such indication for GKRS, they are rare, occurring 15-18 cases per 100,000 adults, with a rupture rate of 2–4% [2]. Vascular malformations are localized collection of abnormal blood vessels having altered blood flow [2]. Clinical presentations include haemorrhage, headaches, seizures, or stroke. AVM are fistulous connections between arteries and veins without capillary involvement with base directed towards meninges and the apex towards ventricular system [3]. There is direct transmission of arterial pressure to venous structures causing increased blood flow, dilation, and vessel tortuosity [4].

Incidence of AVM is at 1.12 to 1.34 per 100,000 individuals or 0.1% of population harbour AVM. Both sexes are affected equally. Annual risk of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is 2-4%. Only 12% of AVMs become symptomatic during life with combined annual morbidity and mortality rate of 1%. The cerebral AVMs are seen in 1.4% to 4.3% of autopsies [5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Treatment modalities for symptomatic AVMs includes surgery, embolization and GKRS. The drawback of GKRS is latency period (2 years). The effectiveness of GKRS depends on location and size of the lesion. GKRS is a well-established treatment modality for cerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), offering high obliteration rates with relatively low morbidity. [10]. Successful AVM treatment with Gamma Knife radiosurgery eliminates the risk of intracranial haemorrhage, complete nidal obliteration, limiting the development of new deficit from radiation-induced changes [11].

Florez-Perdomo et al., (2024) evaluated the safety and effectiveness of GKRS for paediatric AVMs, reporting a 71.64% complete obliteration rate and a low mortality rate of 0.75% [12]. Complications are rebleed and partial obliteration. Dose requirements are determined by location and the size often using the Spetzler-Martin (SM) grading of AVM. [6, 13].

Myeong et al. (2024) demonstrated that time-staged GKRS is a feasible approach for managing large AVMs, achieving satisfactory obliteration rates with acceptable complications [14].

The objective of the present study aims to evaluate the clinical and radiological outcomes of GKRS in AVM management, focusing on nidus obliteration, symptom resolution, and predictive factors such as AVM volume, Spetzler-Martin grade, and radiation dose. It also examines the latency period for obliteration and potential complications.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

This study was conducted in the Department of Neurosurgery, a tertiary care centre, New Delhi, for the duration of two years (September 2019 to September 2021) to evaluate the outcomes of Gamma knife radiosurgery (GKRS) in patients with intracranial AVM. The Department is a tertiary neurosurgery centre with a dedicated GKRS unit. A total of 40 patients (N) were studied.

Ethical clearance was obtained, and informed consent was secured from all participants.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients with clinical and radiological diagnoses of intracranial AVM who were treated with GKRS were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria included other structural abnormalities in addition to AVMs, patient’s unwillingness to participate in the study and patient’s unwillingness to undergo GKRS for intracranial AVMs.

Study Design

This was a non-randomized retrospective cum prospective observational study.

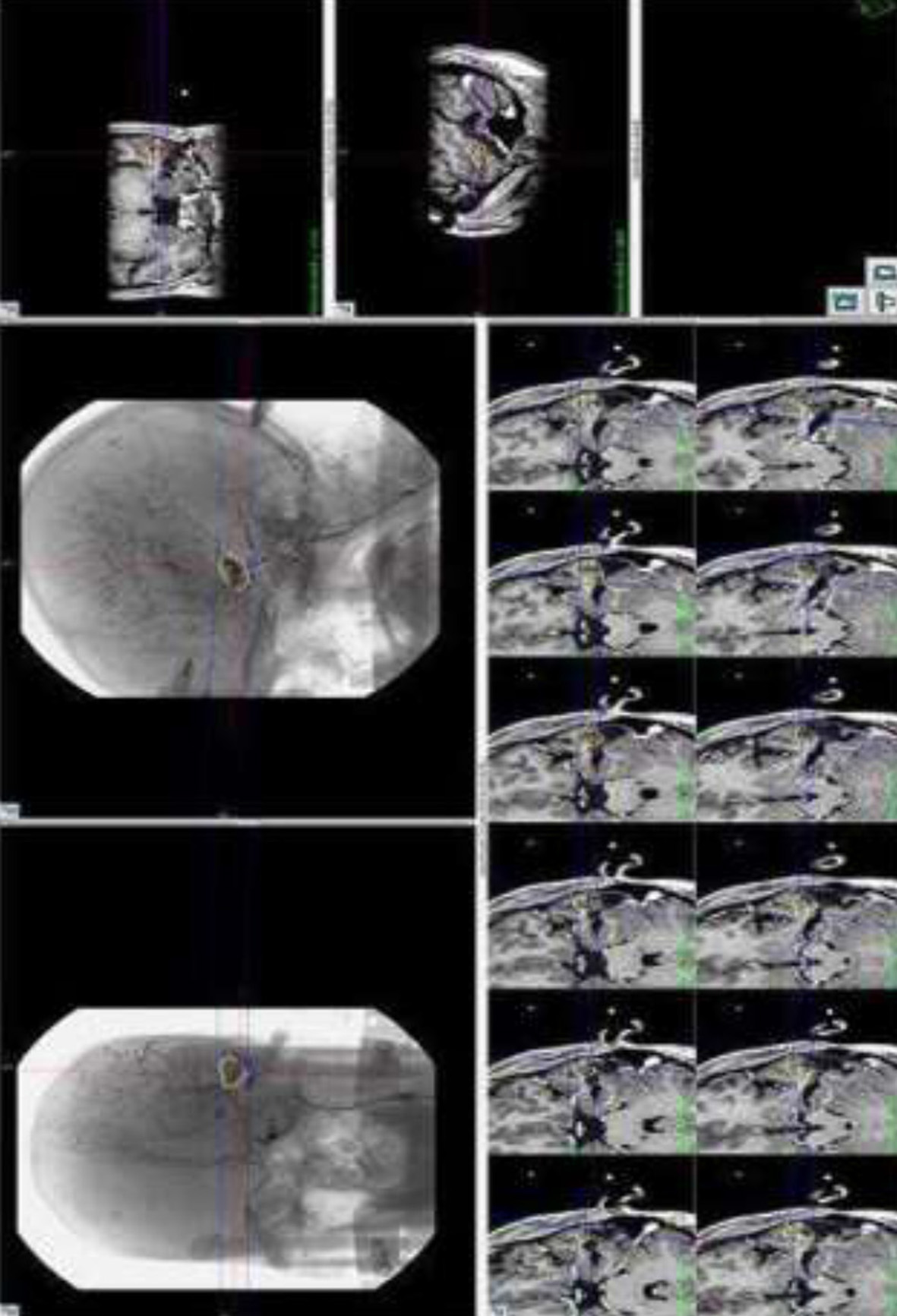

The primary outcome was AVM nidus obliteration following GKRS. Secondary outcomes included demographic factors (age, sex), clinical presentation (symptoms, neurological deficits), AVM characteristics (nidus volume, Spetzler-Martin grade, location, venous drainage), radiation dose delivered, and treatment-related complications. Imaging included CT and CT Angiography, MRI and MR Angiography with digital subtraction angiography (DSA). For GKRS, Leksell Gamma knife (LKG) model 4C (Elekta, Sweden) was used (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Elekta Icon Gamma Knife machine installed at our center

The AVM volumes were estimated by using the formulas V = 0.513× (AP×ML×CC) + 0.047 and V = 0.444 × (AP× ML×CC) + 0.339) for diameters in the range 0–2.5cc and 2.5–36cc respectively with a bias of 0.0005cc and 0.007cc respectively [15].

Selection bias was minimized by including all eligible patients treated during the study period, while measurement bias was reduced through standardized imaging protocols and independent assessments by a multidisciplinary GKRS team, including neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, neurointerventional radiologists, and medical physicists. Decision for appropriateness of GKRS was carried out on case-to-case basis keeping the institutional policy guidelines. The study included 40 patients, based on available cases over the two-year study period.

Quantitative variables including age, nidus volume, radiation dose, percentage of nidus obliteration and follow-up duration, were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables, such as gender, symptoms, AVM location, venous drainage, and Spetzler-Martin grade, were presented as absolute numbers and percentages.

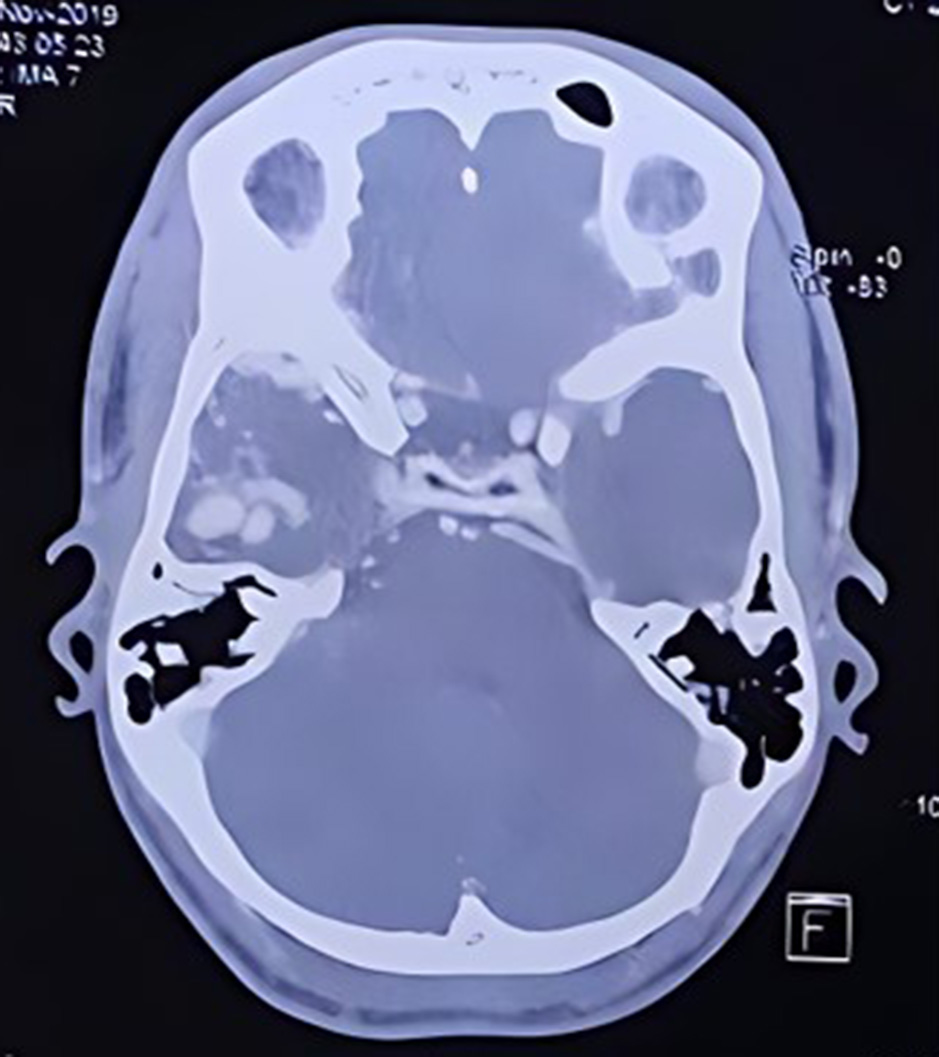

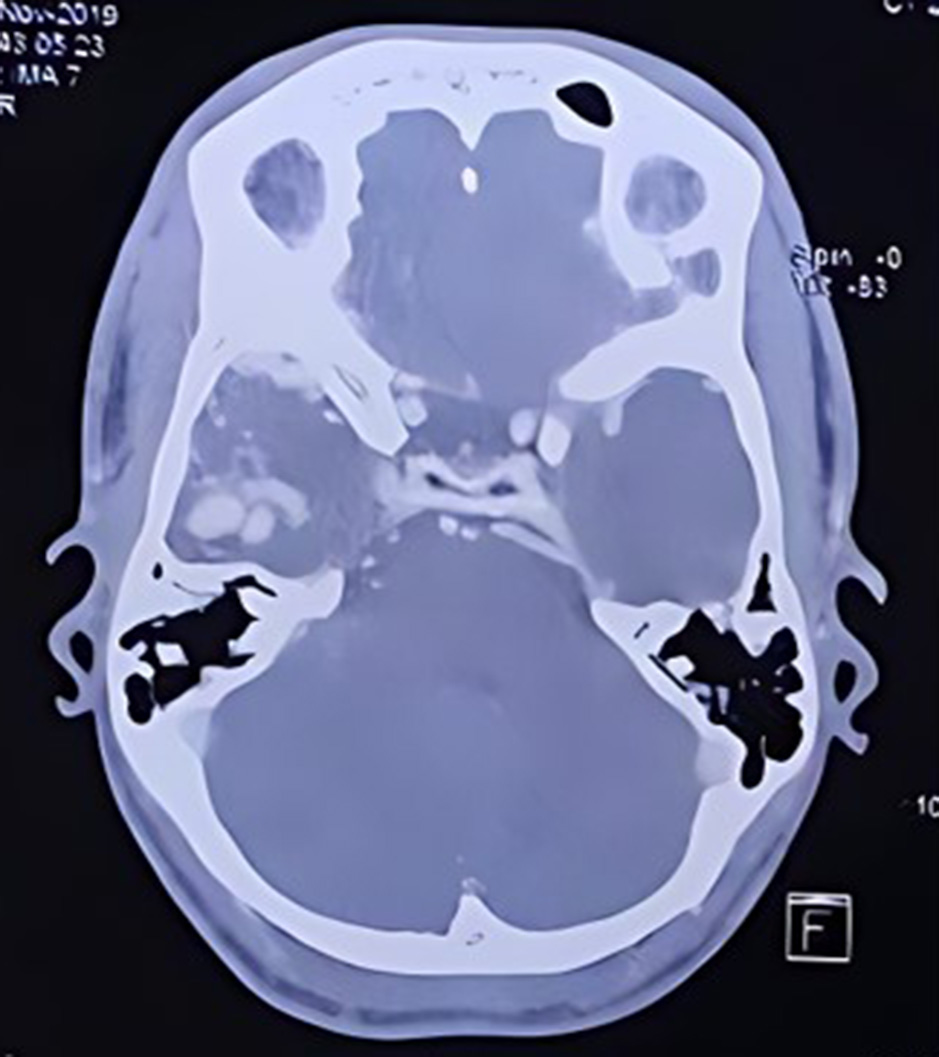

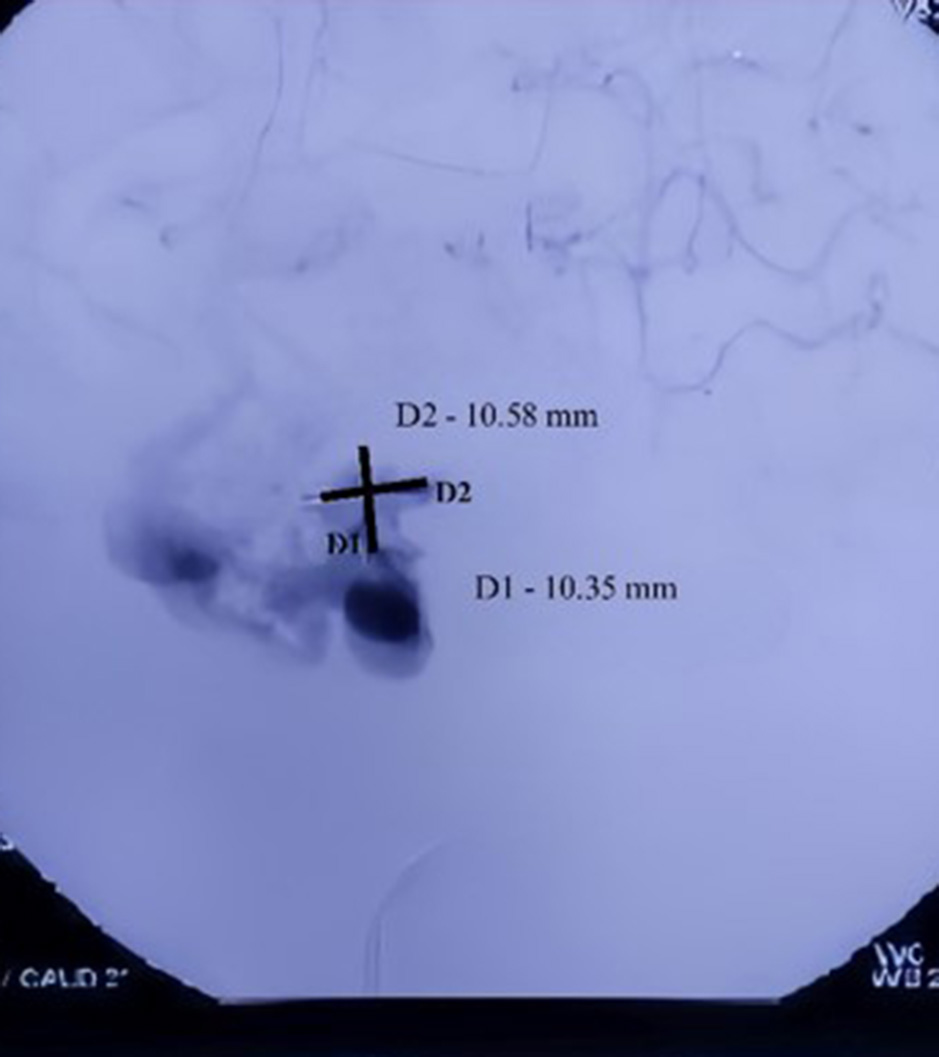

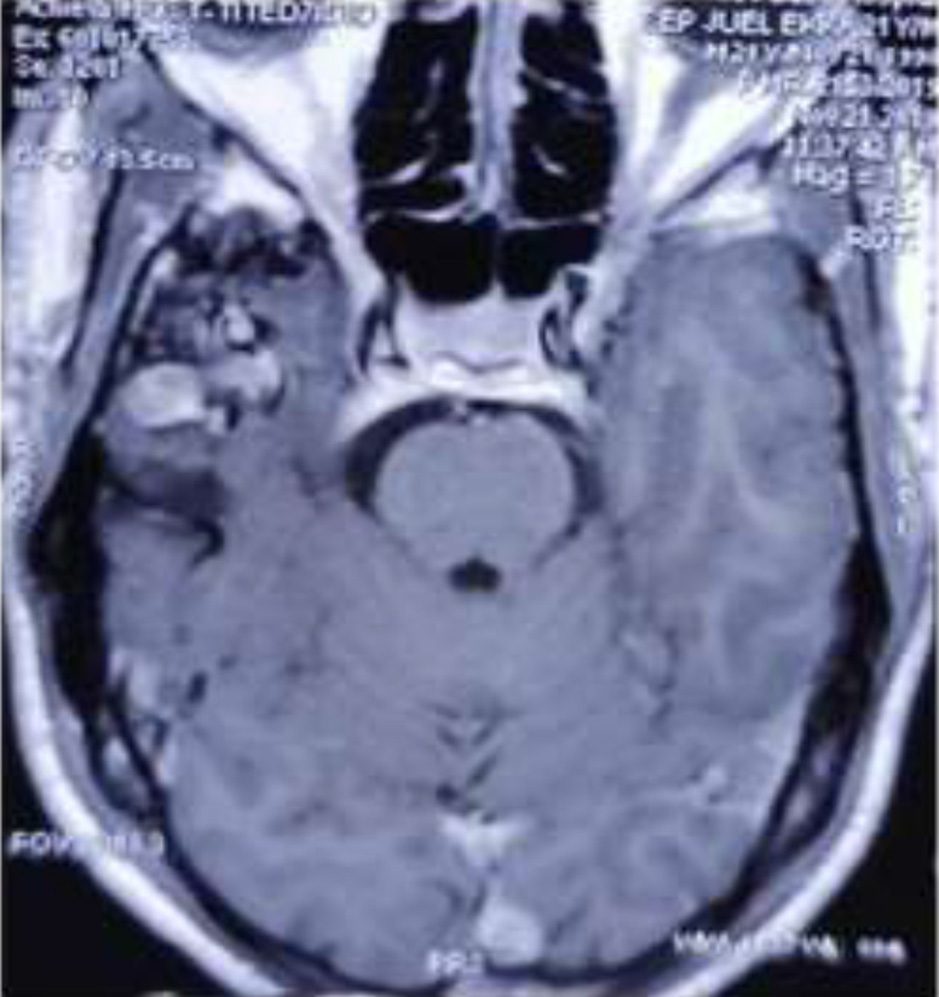

Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5 are the representative images of the patients, showing the AVM, its localisation and planning for purely descriptive purpose only.

Fig. 2. CT angiogram cerebral vessels showing AVM in the Right temporal region

Fig. 3. Digital subtraction angiogram of the left anterior oblique view showing AVM in the Right temporal region with the nidus dimension of 10.35 mm (D1) and 10.58 mm (D2)

Fig. 4. MRI Brain axial view showing AVM in the Right temporal region

Fig. 5. Representative image showing I Gamma Knife Planning for Left temporal AVM Management

Table 1 is the SM grades under which the patients of AVM were classified.

Table 1. Spetzler–Martin Grading System for Brain AVMs

|

Size of Nidus |

Points |

Eloquence of adjacent brain tissue |

Points |

Pattern of venous drainage |

Points |

|

Small (<3cm) |

1 |

No |

0 |

Superficial |

0 |

|

Medium (3-6 cm) |

2 |

Yes |

1 |

Deep |

1 |

|

Large (> 6cm) |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Note.

Eloquent Brain includes the sensorimotor cortex, language/visual cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, internal capsule, brainstem, cerebral peduncles, and deep cerebellar nuclei.

Venous Drainage: Superficial if via cortical veins, Deep if involving internal cerebral veins, basal veins, or the precentral cerebellar vein.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of means were conducted using the independent Student’s t-test for continuous variables, while categorical variables were analysed using the Chi-square test and ANOVA for subgroup comparisons. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0.

Results

In demographic profile of the patients, the male predominance was seen with age group 20 - 40 years. Hemorrhage was initial presentation. Most AVMs were located supratentorially predominantly in lobar regions. A majority of the patients had superficial venous drainage and belonged to SM grade 2, with 87.5% of those patients having complete nidus volume reduction seen after 24 months. The mean duration of follow up was 26.4 months.

Table 2 is complete demographic and clinical profile of the patients with AVM characteristics and the treatment outcome.

Table 2. Clinical & treatment outcomes of AVM patients

|

Parameters |

Value |

|

|

Age (In Years) |

16-71 Years |

SD- 16.114 |

|

Gender |

Male |

26 |

|

Female |

14 |

|

|

Presentation |

Intracranial bleed |

34 |

|

Seizures |

06 |

|

|

Symptoms |

Headache |

36 |

|

Vomiting |

28 |

|

|

Loss of consciousness |

13 |

|

|

Focal neurological deficits |

08 |

|

|

AVM Location |

Supratentorial lobar |

28 |

|

Deep seated |

08 |

|

|

Cerebellum |

04 |

|

|

Nidus Volume |

6.482cc (Mean) |

Range 0.05 - 38.68 cc |

|

Venous Drainage |

Superficial |

27 |

|

Deep |

13 |

|

|

SM Grading |

Grade 1 |

01 |

|

Grade 2 |

32 |

|

|

Grade 3 |

07 |

|

|

Grade 4 & 5 |

Nil |

|

|

Radiation Dose |

12 Gy-23 Gy |

SD 3.969 |

|

Complete Nidus Volume Reduction |

SM Grade 1 |

100% |

|

SM Grade 2 |

87.5% |

|

|

SM Grade 3 |

71.4% |

|

|

Complete Obliteration |

After 06 months |

10% |

|

After 12 months |

20% |

|

|

After 18 months |

27.5% |

|

|

After 24 months |

60% |

|

|

After >24 months |

85% |

|

Six monthly clinical and radiological assessment was done for a period of 24 months and beyond. Individual variables were studied using test of significance to look for correlation between the variable studied and percentage obliteration of AVM after 24 months. After 24 months of follow-up, our study showed, 100% nidus volume reduction in 34 cases (85%), 75 - 99 % nidus reduction in 5 cases (12.5%), and no nidus volume reduction was seen in 1 case (2.5%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Volumetric reduction in nidus volume during 6 monthly follow-up period

|

Follow up Period (Months) |

N (40) |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

1. Percentage volumetric reduction in nidus volume after 6 months |

||||

|

0 |

24 |

60 |

||

|

1 –24 |

00 |

0 |

||

|

25- 49 |

01 |

2.5 |

||

|

50-74 |

05 |

12.5 |

||

|

75 –99 |

06 |

15 |

||

|

100 |

04 |

10 |

||

|

2. Percentage volumetric reduction in nidus volume after 12 months |

||||

|

0 |

08 |

20 |

||

|

1 –24 |

02 |

05 |

||

|

25- 49 |

06 |

15 |

||

|

50 –74 |

07 |

17.5 |

||

|

75 –99 |

09 |

22.5 |

||

|

100 |

08 |

20 |

||

|

3. Percentage volumetric reduction in nidus volume after 18 months |

||||

|

0 |

01 |

2.5 |

||

|

1 –24 |

01 |

2.5 |

||

|

25- 49 |

03 |

7.5 |

||

|

50 –74 |

11 |

27.5 |

||

|

75 –99 |

13 |

32.5 |

||

|

100 |

11 |

27.5 |

||

|

4. Percentage volumetric reduction in nidus volume at 24 months |

||||

|

0 |

01 |

2.5 |

||

|

1 –24 |

00 |

0 |

||

|

25- 49 |

01 |

2.5 |

||

|

50 –74 |

00 |

00 |

||

|

75 –99 |

14 |

35 |

||

|

100 |

24 |

60 |

||

|

5. Percentage volumetric reduction in nidus volume > 24 months |

||||

|

0 |

01 |

2.5 |

||

|

1 –24 |

00 |

- |

||

|

25- 49 |

00 |

- |

||

|

50 –74 |

00 |

- |

||

|

75 –99 |

05 |

12.5 |

||

|

100 |

34 |

85 |

||

|

6. Complete obliteration of AVM |

||||

|

6 Months |

04 |

10 |

||

|

12 Months |

08 |

20 |

||

|

18 months |

11 |

27.5 |

||

|

24 months |

24 |

60 |

||

|

> 24months |

34 |

85 |

||

On applying paired t-test, to look for the interval change in volume during the follow-up period, the mean change in the volume of the nidus at different points of follow-up that is 06 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months and >24 months increases with the duration of follow up and is statistically significant (p-value <0.05) for all durations (Table 4).

Table 4. Paired sample test to determine the significance of duration of follow-up on the decrease in nidus volume

|

Follow up period (In months) |

Mean |

SD |

t - value |

p- value |

Result (p< 0.05) |

|

0 month |

6.48 |

10.43 |

2.64 |

0.012 |

Significant |

|

0 month |

6.48 |

10.43 |

3.18 |

0.003 |

Significant |

|

0 month |

6.48 |

10.43 |

3.47 |

0.001 |

Significant |

|

0 month |

6.48 |

10.43 |

3.64 |

0.001 |

Significant |

|

0 month |

6.48 |

10.43 |

3.70 |

0.001 |

Significant |

Individual variables were studied using test of significance to look for correlation between the study variable and percentage obliteration >24 months. The results are as under (Table 5).

Table 5. Variables and percentage obliteration

|

Variable |

100% obliteration (>24months) |

< 100% obliteration (> 24 months) |

Total |

|

Age |

|||

|

<40 |

24 |

02 |

26 |

|

>40 |

10 |

04 |

14 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

21 |

05 |

26 |

|

Female |

13 |

01 |

14 |

|

Presentation |

|||

|

Bleed |

29 |

05 |

34 |

|

Seizures |

05 |

01 |

06 |

|

Location |

|||

|

Lobar |

22 |

06 |

28 |

|

Cerebellar |

04 |

- |

04 |

|

Deep Seated |

08 |

- |

08 |

|

Venous drainage |

|||

|

Superficial |

10 |

03 |

13 |

|

Deep |

24 |

03 |

27 |

|

Radiation Dose |

|||

|

SM 1 |

01 |

00 |

01 |

|

SM 2 |

28 |

04 |

32 |

|

SM 3 |

05 |

02 |

07 |

|

Volume of AVM |

|||

|

4CC |

26 |

01 |

27 |

|

> 4CC |

08 |

05 |

13 |

The obliteration percentage was higher in younger age (< 40 years), on applying Chi square test to analyse the effect of age on obliteration percentage the p-value was 0.777, which was not significant. The percentage obliteration in patients presented with bleed and seizure was 85.3% and 83.3%, respectively p-value was 0.901, not significant. The percentage of obliteration of AVM nidus was 100% in cerebellar and deep-seated AVM as compared to the lobar AVMs (78.5%), the difference was not statistically significant (p-value 0.220). Percentage obliteration is higher in AVMs having deep venous drainage than superficial venous drainage (88.8% vs 76.9%). The difference was statistically not significant (p-value 0.320). The percentage obliteration of AVM nidus is higher in lower SM grade AVM (100% in SM grade 1 and 87.5% in SM grade 2) as compared to SM grade 3 (71.4%) after 24 months. The difference was not statistically significant (p value= 0.510). At 24 months post GKRS, the lower volume of AVM (<4cc) showed higher percentage of obliteration than those with higher nidus volume (>4cc) that is 96.2% vs 61.5%. The difference in the percentage obliteration was statistically significant (p-value = 0.003). This means that small nidus volume (< 4cc) is having a better obliteration rate than large nidus volume (>4cc) and the p-value is statistically significant. Notably, 100% of cases having nidus volume <1cc showed complete obliteration. In the present study it is seen that, with the increase in duration of follow-up, there is gradual increase in the percentage of obliteration of AVM nidus and decrease in the mean nidus volume. On applying paired t-test, to look for the interval change in volume during the follow-up period, the mean change in the volume of the nidus at different points of follow-up that is 06 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months and >24 months increases with the duration of follow up and is statistically significant (p-value <0.05) for all durations.

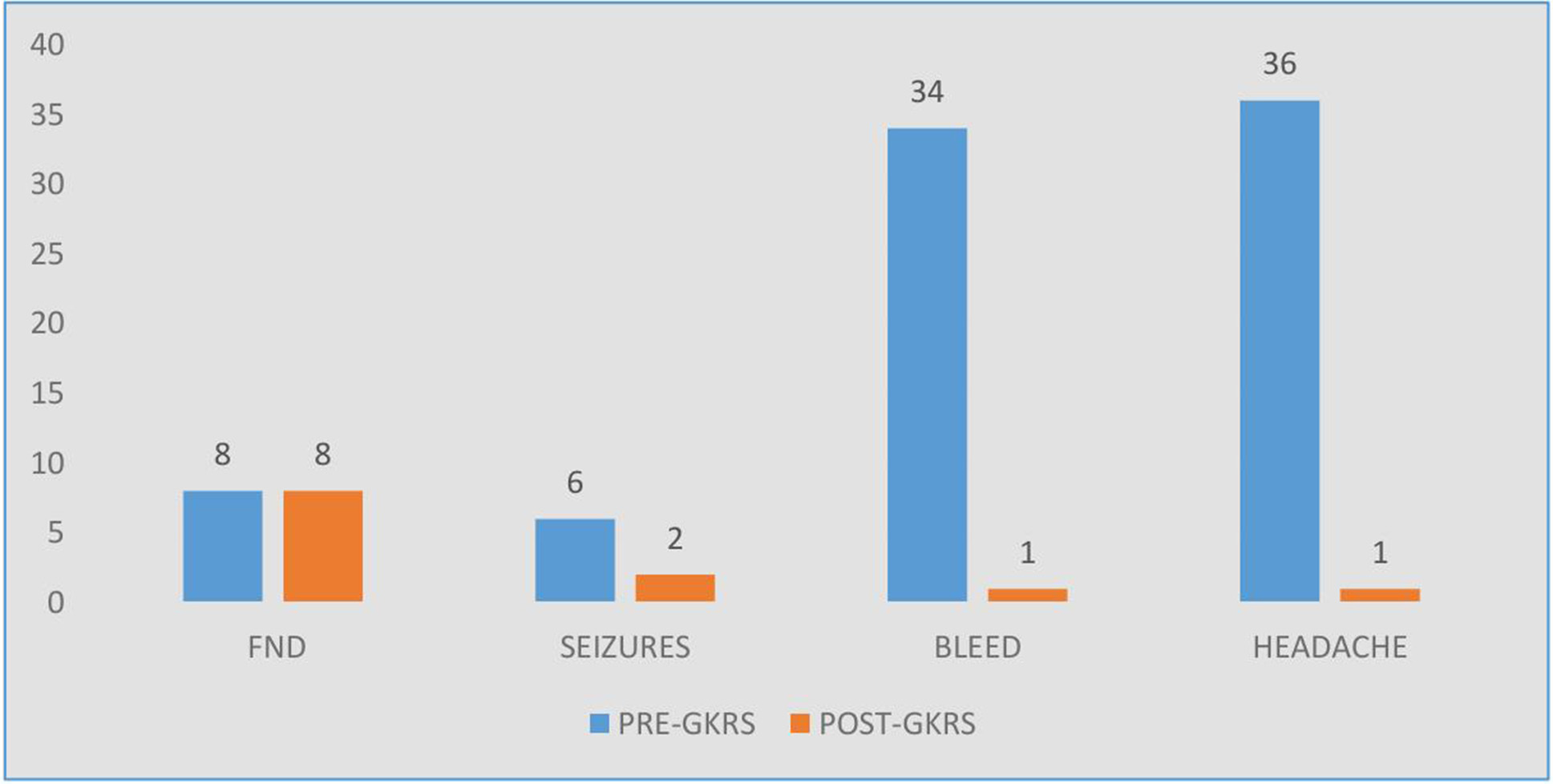

After 24 months of follow up, there was significant improvement in various symptoms except focal neurological deficits which persisted even after the procedure with some improvement in the grade of the deficits (Fig. 6).

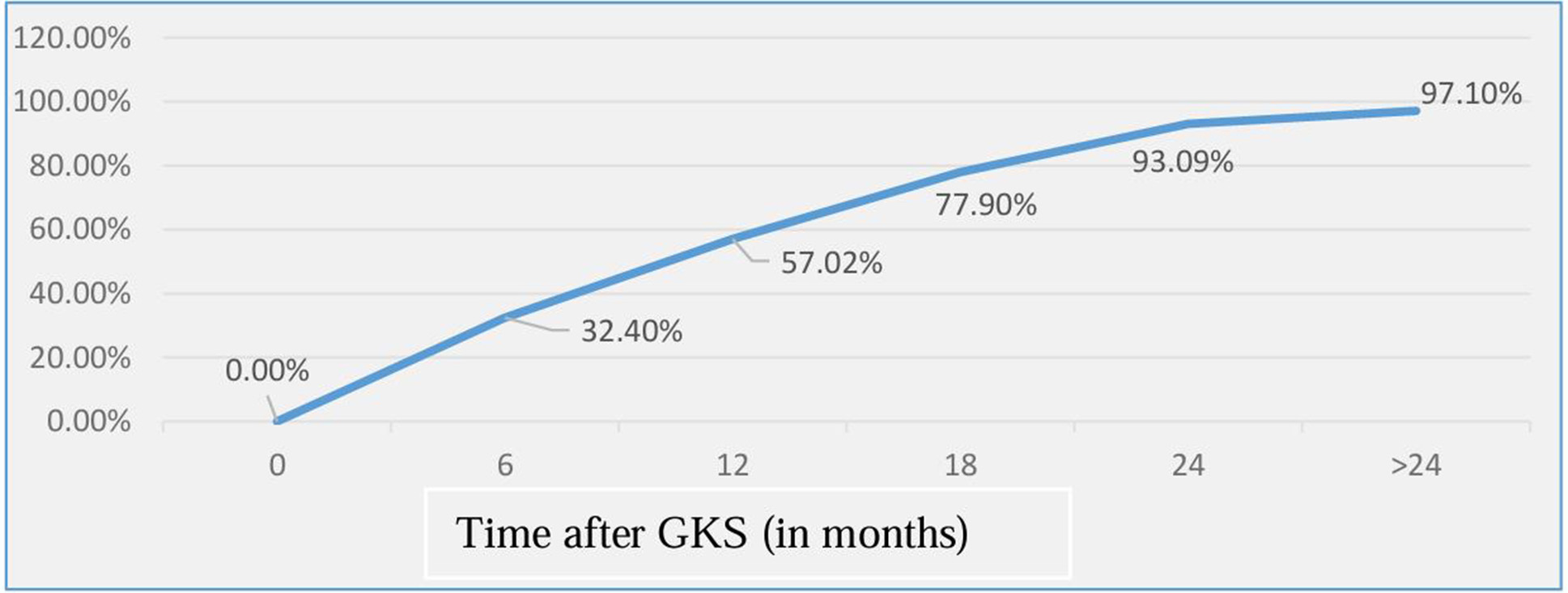

Kaplan Meier graph was plotted to look for the actual obliteration rates. It was found that the obliteration rate of 32.4%, 57.02%, 77.90%, 93.09% and 97.10% at6, 12, 18, 24 and >24 months respectively (Fig. 7). Though the mean volume of obliteration increased with time during each point of follow-up, however on comparing between the groups using ANOVA test, the results were statistically not significant.

The rate of obliteration or volume reduction of AVM nidus follows a steep curve till about two years and then gradually attains a plateau. Thus, it may be inferred that to attain an optimal and desired rate of obliteration of AVM nidus, minimum duration of 2 years should be considered and the patients counselled accordingly. If the response is not achieved till 2 years post procedure, alternate procedure or redo gamma knife can be considered.

Fig. 6. Clinical assessments after 24 months of follow up

Fig. 7. Kaplan-Meier plot of obliteration over time for total patients included in the study.

Discussion

C Hofmeister, C Stapf, et al [16] found that, the mean age at diagnosis was 31.2 years which corresponded with our study (35.4 years). In our study 35% were females compared to 45%, Deep venous drainage was seen in 67.5% as compared to 55%. AVMs in eloquent locations was found in 20% of cases in our study as compared to 71%. Haemorrhage was seen in 85% of our cases as compared to 53 % and seizures were seen only in 15% in our study as compared to 30%. Headache was seen in 90% of our cases as compared to 14%, neurological deficits were seen in 20% of our cases as compared to 70%.

J Hillman [17] mentioned high-grade AVMs were rare with SM Grades 1 to 3 representing 85% of cases which corresponded with our study. Haemorrhage was the initial manifestation in 69.6% of the cases as compared to 85% of our study.

AVM presents in the age group of 10-40 years with male preponderance [18] which corresponded to our study. The most common presentation was haemorrhage and seizure [19] In our study, haemorrhage was seen in 85% of cases and seizures in 15%. In one study headache was seen in 5-14% [20] [21], in our study, most common symptom was headache (n=36), followed by vomiting (n=28) and loss of consciousness(n=13). Factors predisposing to focal neurological deficits include increasing age, female gender, deep brain location and venous drainage pattern [22] We could not find any such correlation; however, deep seated AVM was predisposing factor for neurological deficits (5 / 8).

Kim B.S. et al [23], Ding D. et al [24] found 90.2% of AVMs were supratentorial in location with deep venous drainage in 24.6% with SM grade 2 or 3 (32.9% each) which corresponded with our study.

Flickinger J.C. et al [25] studied higher radiation dose, deep location, and prior haemorrhage corelated with increased chances of temporary or permanent neurological deficits. In our study, out of the 08 patients who were symptomatic with focal neurological deficits, 05 patients had deeply seated AVM (62.5%) The mean radiation dose given to all the patients who had deficits was 17.3Gy(>12Gy) and all the patient presented with the history of haemorrhage which correlated with the above study. Of the six patients who presented with seizures, four became seizure-free (66.66%) corresponding to 55.17% found by Heikkinen E.R. et al. [26]

Yang S. Y. et al. [27] showed post GKRS seizure outcome improves in patients with AVM related seizures, provided AVM gets obliterated. In our case, the results were inconsistent. Of the six patients who presented to us with seizures, two patients continued to have seizure even after 100% obliteration of the nidus.

In most series, the obliteration rate following GKRS was > 70% with a range varying from 35% to 92%. Small AVMs had obliteration rate >80% in most series. Time interval between the GKRS and complete obliteration of AVM nidus may range from 1 to 4 years or even longer. The maximum chances of obliteration are during first three years of GKRS.

In our case, the obliteration percentage after 24 months of follow-up was about 85%. Burrow et al. in 2014 [28] studied 80 patients of small AVMs and found the obliteration rate of about 92%, he did not mention the volume of the nidus. In our case, the obliteration rate was in 96% of patients with AVM for nidus volume < 4cc and 62 % obliteration for the nidus volume > 4 cc. Ding et al. [29] studied obliteration rates on 639 cases of ruptured AVMs and achieved an obliteration rate of 67.1% with a mean radiation dose of 21.7 Gy and a mean follow-up of 57.2 months. In our study, the obliteration rate was 85% and a mean dose given was 18.04 Gy with a mean follow-up of 36.4 months.

Thenier et al. [30] reported in a single centre study an overall obliteration rate of 81%. Positive predictors of nidus obliteration included nidus diameter and venous drainage. Ruptured status of AVM had no effect and low-grade AVMs were associated with higher obliteration rates. Similarly, in our study lower SM grade that is SM grade 1 and 2 had a higher percentage obliteration rate (100% and 87.5% respectively) than SM grade 3 (71.4%). Deep venous drainage was related to higher obliteration rate as compared to superficial drainage (88.8% vs 76.9%).

Сonclusion

GKRS is an effective treatment for achieving obliteration of brain AVMs. In our study initial volume of nidus and the duration following GKRS are the important predictors for the obliteration of AVM and the p-values came out to be significant (<0.05). Cerebellar and deep seated AVMs had 100% nidus obliteration. SM Grade I had 100% nidus obliteration and Grade II had 87.5% obliteration, however the p -values for the above variable were non-significant. In spite of lack of statistical significance for the above variables the high percentage of obliteration observed in these variables play an important role and are clinically relevant.

The other variables, such as higher prescription dose, deep venous drainage, female gender, and young age although had a high percentage obliteration are also clinically relevant, though the p-values for them were also not significant (p-value >0.05).

Disclosure

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Funding

The study received no sponsorship or financial support.

References

1. Furlan AJ, Whisnant JP, Elveback LR. The decreasing incidence of primary intracerebral hemorrhage: a population study. Ann Neurol. 1979 Apr;5(4):367-73. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410050410

2. McCormick WF. The pathology of vascular ("arteriovenous") malformations. J Neurosurg. 1966 Apr;24(4):807-16. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1966.24.4.0807

3. Kalimo H, Kaste M, Haltia M. In: Graham DI, Lantos PI, editors. Greenfield’s Neuropathology. 6th ed. London: Arnold; 1997.

4. Laakso A, Hernesniemi J. Arteriovenous malformations: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2012 Jan;23(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2011.09.012

5. Al-Shahi R, Bhattacharya JJ, Currie DG, Papanastassiou V, Ritchie V, Roberts RC, Sellar RJ, Warlow CP; Scottish Intracranial Vascular Malformation Study Collaborators. Prospective, population-based detection of intracranial vascular malformations in adults: the Scottish Intracranial Vascular Malformation Study (SIVMS). Stroke. 2003 May;34(5):1163-9. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000069018.90456.C9

6. Stapf C, Mast H, Sciacca RR, Berenstein A, Nelson PK, Gobin YP, Pile-Spellman J, Mohr JP; New York Islands AVM Study Collaborators. The New York Islands AVM Study: design, study progress, and initial results. Stroke. 2003 May;34(5):e29-33. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000068784.36838.19

7. Graf CJ, Perret GE, Torner JC. Bleeding from cerebral arteriovenous malformations as part of their natural history. J Neurosurg. 1983 Mar;58(3):331-7. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1983.58.3.0331

8. Ondra SL, Troupp H, George ED, Schwab K. The natural history of symptomatic arteriovenous malformations of the brain: a 24-year follow-up assessment. J Neurosurg. 1990 Sep;73(3):387-91. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1990.73.3.0387

9. Rumbaugh CL, Potts DG. Skull changes associated with intracranial arteriovenous malformations. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1966 Nov;98(3):525-34. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.98.3.525

10. China M, Vastani A, Hill CS, Tancu C, Grover PJ. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for cerebral arteriovenous malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2022 Jun;45(3):1987-2004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-022-01751-1

11. Osipov A, Koennecke HC, Hartmann A, Young WL, Pile-Spellman J, Hacein-Bey L, Mohr JP, Mast H. Seizures in cerebral arteriovenous malformations: type, clinical course, and medical management. Interv Neuroradiol. 1997 Mar 30;3(1):37-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/159101999700300104

12. Florez-Perdomo WA, Reyes Bello JS, Moscote Salazar LR, Agrawal A, Janjua T, Chavda V, et al. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Egypt J Neurosurg. 2024;39(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-024-00307-3

13. Toffol GJ, Biller J, Adams HP Jr. Nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage in young adults. Arch Neurol. 1987 May;44(5):483-5. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1987.00520170013014

14. Myeong HS, Jeong SS, Kim JH, Lee JM, Park KH, Park K, Park HJ, Park HR, Yoon BW, Hahn S, Lee EJ, Kim JW, Chung HT, Kim DG, Paek SH. Long-Term Outcome of Time-Staged Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for Large Arteriovenous Malformations. J Korean Med Sci. 2024 Jul 29;39(29):e217. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e217

15. Singhal S, Gill M, Srivastava C, Gupta D, Kumar A, Kaushik A, Semwal MK. Simplifying Tumor Volume Estimation from Linear Dimensions for Intra-Cranial Lesions Treated with Stereotactic Radiosurgery. J Med Phys. 2020 Oct-Dec;45(4):199-205. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmp.JMP_56_20

16. Hofmeister C, Stapf C, Hartmann A, Sciacca RR, Mansmann U, terBrugge K, Lasjaunias P, Mohr JP, Mast H, Meisel J. Demographic, morphological, and clinical characteristics of 1289 patients with brain arteriovenous malformation. Stroke. 2000 Jun;31(6):1307-10. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.31.6.1307

17. Hillman J. Population-based analysis of arteriovenous malformation treatment. J Neurosurg. 2001 Oct;95(4):633-7. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2001.95.4.0633

18. Gross CR, Kase CS, Mohr JP, Cunningham SC, Baker WE. Stroke in south Alabama: incidence and diagnostic features--a population based study. Stroke. 1984 Mar-Apr;15(2):249-55. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.15.2.249

19. da Costa L, Wallace MC, Ter Brugge KG, O'Kelly C, Willinsky RA, Tymianski M. The natural history and predictive features of hemorrhage from brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke. 2009 Jan;40(1):100-5. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.524678

20. Stapf C, Mast H, Sciacca RR, Choi JH, Khaw AV, Connolly ES, Pile-Spellman J, Mohr JP. Predictors of hemorrhage in patients with untreated brain arteriovenous malformation. Neurology. 2006 May 9;66(9):1350-5. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000210524.68507.87

21. Arteriovenous Malformation Study Group. Arteriovenous malformations of the brain in adults. N Engl J Med. 1999 Jun 10;340(23):1812-8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199906103402307

22. Choi JH, Mast H, Sciacca RR, Hartmann A, Khaw AV, Mohr JP, Sacco RL, Stapf C. Clinical outcome after first and recurrent hemorrhage in patients with untreated brain arteriovenous malformation. Stroke. 2006 May;37(5):1243-7. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000217970.18319.7d

23. Kim BS, Yeon JY, Kim JS, Hong SC, Shin HJ, Lee JI. Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for ARUBA-Eligible Patients with Unruptured Brain Arteriovenous Malformations. J Korean Med Sci. 2019 Sep 23;34(36):e232. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e232

24. Ding D, Yen CP, Starke RM, Xu Z, Sun X, Sheehan JP. Radiosurgery for Spetzler-Martin Grade III arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2014 Apr;120(4):959-69. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.12.JNS131041

25. Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Pollock BE, Yamamoto M, Gorman DA, Schomberg PJ, Sneed P, Larson D, Smith V, McDermott MW, Miyawaki L, Chilton J, Morantz RA, Young B, Jokura H, Liscak R. A multi-institutional analysis of complication outcomes after arteriovenous malformation radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 Apr 1;44(1):67-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00518-5

26. Heikkinen ER, Konnov B, Melnikov L, Yalynych N, Zubkov YuN, Garmashov YuA, Pak VA. Relief of epilepsy by radiosurgery of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1989;53(3):157-66. https://doi.org/10.1159/000099532

27. Yang SY, Kim DG, Chung HT, Paek SH. Radiosurgery for unruptured cerebral arteriovenous malformations: long-term seizure outcome. Neurology. 2012 Apr 24;78(17):1292-8. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825182c5

28. Burrow AM, Link MJ, Pollock BE. Is stereotactic radiosurgery the best treatment option for patients with a radiosurgery-based arteriovenous malformation score ≤ 1? World Neurosurg. 2014 Dec;82(6):1144-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.009

29. Ding D, Yen CP, Starke RM, Xu Z, Sheehan JP. Radiosurgery for ruptured intracranial arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2014 Aug;121(2):470-81. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.2.JNS131605

30. Thenier-Villa JL, Galárraga-Campoverde RA, Martínez Rolán RM, De La Lama Zaragoza AR, Martínez Cueto P, Muñoz Garzón V, Salgado Fernández M, Conde Alonso C. Linear Accelerator Stereotactic Radiosurgery of Central Nervous System Arteriovenous Malformations: A 15-Year Analysis of Outcome-Related Factors in a Single Tertiary Center. World Neurosurg. 2017 Jul;103:291-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.081