Ukrainian Neurosurgical Journal. 2025;31(Special issue):3-27

https://doi.org/10.25305/unj.313858

Authors:

Background: Neuropathic pain is a condition of complex nature arising from damage to or dysfunction of the sensory nervous system. Conventional treatment options (like antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids) frequently have limited efficacy and substantial side effects. Thereat, increasing attention is being paid to botulinum toxin therapy (BTT) as a promising option for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

Purpose: To develop the Ukrainian national consensus statement on the use of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) to treat neuropathic pain through the review of available literature, compilation of experience of Ukrainian specialists, and formulation of relevant practical recommendations.

Methods: Our working group reviewed the current literature (including randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and personal clinical observations related to the use of BoNT to treat painful neuropathic syndromes.

Results: BoNT demonstrated high efficacy in the treatment of neuropathic pain, particularly in postherpetic neuralgia, painful diabetic neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, post-amputation pain, trauma sequelae, spinal cord injury and other conditions. Its major pain relief mechanisms include modulation of neuronal activity, blocking the release of pain neuromediators, and neuroplastic effects. The optimal dosage amount was found to vary from 50 to 300 units, depending on the affected area, with mostly subcutaneous or intradermal BoNT injections used.

Conclusion: BTT is a safe promising treatment option for neuropathic pain and can be used either alone or in combination with other pain relief modalities. Our working group developed practical recommendations on BoNT indications, doses and injection techniques in painful neuropathic syndromes which can be implemented into clinical practice to improve patients’ quality of life.

Keywords: botulinum neurotoxin; neuropathic pain; postherpetic neuralgia; painful diabetic neuropathy; trigeminal neuralgia; post-amputation pain; phantom limb pain; spinal cord injury sequelae; botulinum toxin therapy

Introduction

The problem of chronic pain is still far from being solved. In a survey of chronic pain in Europe, the prevalence of chronic moderate-to-severe non-cancer pain in adults was estimated at 19% [1]. Neuropathic pain (NP) develops as a result of lesions or disease affecting the nervous system and patients with NP contribute significantly to the number of individuals with chronic non-cancer pain. Chronic pain affects general health, impairs work capacity and everyday activities, negatively impacts economic well-being and interpersonal relations, and is significantly associated with depression symptoms. Patients and physicians are often dissatisfied with the efficacy of available treatments for chronic pain. For patients with moderate-to-severe chronic non-cancer pain, 40% were not satisfied with their pain treatment [1].

All this warrants the search for advanced and more effective treatment options and technologies. After the findings of the analgesic effects of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) in some chronic pain disorders (e.g., NP disorders) were published, there was an enormous growth in publications on successful application of BoNT in NP, ranging from case reports to results of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and special monographs like two editions of “Botulinum toxin treatment of pain disorders” [2] by Bahman Jabbari, Professor of Neurology at Yale University.

The botulinum toxin approach to chronic pain has gained advocates also in Ukraine. This occurred partly due to increasing number of victims of war with the NP associated, among other factors, with limb injury and/or amputation. The Ukrainian specialists advocating for the botulinum toxin approach have united in a working group to develop the Ukrainian National Consensus Statement on Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Neuropathic Pain. Our aim was three-fold: (i) to review the available literature on the use of BoNT in NP disorders, (ii) to create a compilation of experience of Ukrainian colleagues dealing with this approach, and (iii) to formulate practical recommendations on potential indications for BoNT in painful neuropathic conditions and injection targets, techniques, and doses. We hope that the results of our work will be helpful for managing pain in those who need it most.

Pain pathophysiology. Neuropathic pain

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has defined pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” [3].

Pain has diverse etiologies, pathophysiological mechanisms, and clinical characteristics, and different methods and means of pain management are available for different types of pain. Traditionally, pain has been divided into two categories, “nociceptive pain” and “neuropathic pain”; these categories differ in characteristics and underlying mechanisms. Nociplastic (or dysfunctional) pain is the term suggested in 2016 to describe a third category of pain that is distinct from those above mentioned and can be mechanistically defined as pain arising from the altered function of pain-related sensory pathways in the periphery and central nervous system (CNS) [4].

Nociceptive pain

Nociceptive pain is a normal body response to noxious or potentially dangerous factors (primarily, tissue damage due to injury or inflammation).

Mechanism. Nociceptive pain arises when nociceptors (special sensory nerve endings) are activated by noxious stimuli. These stimuli may be thermal (heat or cold), mechanical (pressure or trauma) or chemical (inflammatory mediators) in nature.

Characterization. Nociceptive pain is usually well localized and proportional to tissue damage. It acts as an early warning system, telling the body to take evasive action.

Examples of nociceptive pain are pain from a paper cut, an infection, a broken bone, or osteoarthritis [5].

Neuropathic pain

NP is chronic pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system.

Mechanism. NP arises from abnormal pain processing in the nervous system, including alterations in nerve function, neuromediator activity and CNS function.

Characterization. NP is often described as burning, lancinating, pricking or electric shock-like. It can be spontaneous, evoked by non-noxious stimuli (allodynia), or take a chronic course.

Causes. The cause can be a metabolic disease, e.g., diabetic neuropathy, a neurodegenerative, vascular or autoimmune condition, a tumor, trauma, infection, exposure to toxins, or a hereditary disease.

The fundamental difference between NP and nociceptive pain is in their origin: the latter results from tissue damage and activation of nociceptors, whereas the former is caused by nervous system dysfunction and includes abnormal pain processing in the nervous system.

The mechanisms that underlie nociplastic pain are not entirely understood, but it is thought that augmented CNS pain, sensory processing and altered pain modulation play prominent roles. The symptoms observed in nociplastic pain include multifocal pain that is more widespread or intense, or both, that would be expected given the amount of identifiable tissue or nerve damage, as well as other CNS-derived symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep, memory, and mood problems. This type of pain can occur in isolation, as often occurs in conditions such as fibromyalgia or tension-type headache, or as part of a mixed-pain state in combination with ongoing nociceptive or NP, as might occur in chronic back pain [2, 4, 6].

Key pathophysiological aspects of neuropathic pain

NP may be categorized as peripheral NP and central NP. The difference between peripheral NP and central NP is the location of the pathological process leading to dysfunction of pain perception. Peripheral NP arises from damage to peripheral nerves, which may possibly result from disorders like diabetic neuropathy, nerve compression, nerve trauma, or infections affecting peripheral nerves, whereas central NP arises from pathological changes in the CNS, which may possibly result from disorders like spinal cord trauma, stroke, MS and neurodegenerative diseases [7, 8].

Neuropathic pain epidemiology

The epidemiology of NP reveals a condition that significantly impacts the quality of life (QoL) of affected individuals. As the global population ages and the incidence of chronic conditions rises, the burden of NP is likely to increase. Comprehensive strategies that encompass prevention, early identification, and effective management are essential to mitigate the impact of this debilitating condition on individuals and society as a whole. Addressing the physical and psychosocial dimensions of NP is crucial for improving QoL and ensuring that patients receive the holistic care they require.

NP is a multifaceted condition that arises from damage to the nervous system, leading to a range of sensory abnormalities and significant suffering. The epidemiology of NP is critical not only for understanding its prevalence and risk factors but also for elucidating its profound impact on the QoL of affected individuals.

Prevalence of NP. Epidemiological studies indicate that NP affects approximately 6.9% to 10% of the general population [9, 10, 11]. This prevalence is not uniform and varies significantly across different populations, particularly among those with comorbid conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and MS. For instance, the prevalence of NP in diabetic patients can be as high as 50% [12]. The increasing incidence of these chronic conditions, coupled with an aging population, suggests that the burden of NP will likely rise in the coming years [13]. The variability in prevalence rates can also be attributed to differences in study methodologies, diagnostic criteria, and population demographics.

For instance, a systematic review found that NP prevalence in cancer patients ranged from 19% to 39% [14]. This highlights the importance of context when interpreting prevalence data, as certain groups may experience a disproportionately higher burden of NP.

Impact on QoL. The impact of NP on QoL is profound and multifaceted. Patients often report significant impairments in physical functioning, emotional well-being, and social interactions [15]. The pain associated with neuropathic conditions can lead to a cycle of disability, where the pain exacerbates psychological distress, resulting in further functional decline [16]. Studies have consistently shown that individuals with NP experience higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to those without chronic pain [17].

The relationship between NP and QoL can be understood through various dimensions. Physically, patients may struggle with mobility, leading to decreased participation in daily activities and social engagements. This physical limitation can foster feelings of isolation and helplessness, further exacerbating mental health issues [18]. Emotionally, the persistent nature of NP can lead to a sense of loss, as individuals may feel they are unable to engage in activities they once enjoyed [19]. Moreover, the economic implications of NP are substantial. Patients often face increased healthcare costs due to frequent medical visits, treatments, and potential hospitalizations. Additionally, lost productivity due to pain-related absenteeism can have significant economic repercussions for both individuals and society [20]. A study estimated that the annual cost of NP in the United States exceeds $600 billion, highlighting the extensive burden this condition places on the healthcare system and economy [21].

Mechanisms Underlying QoL Impairment. The mechanisms through which NP affects QoL are complex and multifactorial. NP is characterized by abnormal processing of pain signals in the nervous system, which can result from peripheral nerve injury, central sensitization, or both [22]. This altered pain processing can lead to heightened sensitivity to pain stimuli, making even normally harmless stimuli feel unbearable [23]. Additionally, the neurobiological changes associated with chronic pain can lead to alterations in mood and cognitive function. For instance, chronic pain has been shown to affect neurotransmitter systems involved in mood regulation, such as serotonin and norepinephrine. This biochemical imbalance can contribute to the development of depression and anxiety, further diminishing QoL. Psychosocial factors also play a critical role in the experience of NP. Individuals with a history of trauma, low socioeconomic status, or limited social support may be at greater risk for experiencing severe pain and associated quality of life impairments. Furthermore, the stigma associated with chronic pain can lead to feelings of shame and isolation, compounding the emotional toll of the condition.

Treatment and Management Strategies. Despite the significant impact of NP on QoL, many patients do not receive adequate treatment. Current pharmacological options include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and topical agents, but the response to these treatments can be variable. A substantial number of patients experience inadequate relief from existing therapies, highlighting the need for more effective treatment strategies. Emerging research is focusing on novel therapeutic approaches, including the use of gene therapy and neuromodulation techniques, which may offer hope for patients with refractory NP. Additionally, a multidisciplinary approach that includes psychological support and physical rehabilitation is essential for addressing the complex nature of NP and improving patient outcomes. Integrating cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based interventions has shown promise in alleviating both pain and associated psychological distress.

Botulinum neurotoxin: Nature, mechanism of analgesic effect of, and immunogenicity issues related to

BoNT is a neurotoxin produced by the gram-positive, anaerobic bacillus Clostridium botulinum. In early 19th century, BoNT as the causative agent of botulism was discovered by the German physician Justinus Kerner, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the American ophthalmologist Alan Scott was the first to use it for therapeutic purposes (namely, for the treatment of strabismus). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved BoNT-A for the treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, and hemifacial spasm in 1989 [24, 25].

BoNTs are categorized into at least seven toxinotypes, termed A–G, two of which, types A and B, have been studied most intensively and used widely in clinical practice [25]. BoNT-A has been widely used in the clinical practice (particularly in neurology) for the treatment of blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, cervical dystonia, sialorrhea, primary axillary hyperhidrosis, spasticity, chronic migraine, myofascial pain, and NP [26].

The unique mechanism of action of BoNT-A involves its enzymatic activity, where the toxin cleaves neuronal vesicle-associated proteins responsible for acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction [27]. This enzymatic action not only leads to muscle paralysis but also influences neurotransmitter release and neuronal signaling, affecting pain processing pathways in neuropathic conditions.

A BoNT molecule, particularly BoNT-A, has demonstrated significant potential in managing NP through its unique ability to modulate pain signaling pathways and inhibit neurotransmitter release. One critical aspect that enhances the efficacy of botulinum toxin as an antineuropathic agent is its neuronal affinity and the complex process of molecular transport from the periphery towards the Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRG) [28]. Research indicates that BoNT molecules can travel between the periphery and the Central Nervous System (CNS) through dual anterograde and retrograde axonal transport via motor or sensory neurons [28]. This bidirectional transport mechanism enables botulinum toxin to effectively reach target sites, including the DRG, where it can exert its antinociceptive effects.

Further studies have emphasized the importance of axonal transport in facilitating the antinociceptive actions of BoNT in NP conditions. BoNT-A has been shown to undergo axonal transport to trigeminal sensory areas, resulting in reduced neuronal and glial activation in central nociceptive regions associated with pain processing [29]. This transport to specific sensory areas is crucial in modulating pain perception and reducing hypersensitivity in NP states.

Additionally, the retrograde axonal transport of BoNT-A has been implicated in its ability to manage chronic pain by acting on peripheral nociceptive neurons and inducing central desensitization through toxin transport to the CNS [30]. By retrograde traveling through central neurons and motor neurons, BoNT-A can reach the spinal cord and other pain processing centers, where it can modulate pain signaling and alleviate NP symptoms [31]. This retrograde transport mechanism underscores the targeted and specific action of BoNT-A in addressing NP.

Moreover, BoNT-A has been shown to exhibit trans-synaptic transport properties, allowing it to move into inhibitory nerve terminals and block the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters. This action ultimately disinhibits lower motor neurons and influences pain perception [32]. This trans-synaptic movement highlights BoNT-A’s ability to modulate neuronal activity and synaptic transmission, contributing to its antinociceptive effects in NP conditions.

Therefore, the neuronal affinity and transport mechanisms of BoNT-A play a crucial role in its effectiveness as an antineuropathic agent. Through axonal transport, retrograde movement, and trans-synaptic inhibition, BoNT-A can reach target sites in the CNS, including the DRG, to modulate pain signaling pathways, inhibit neurotransmitter release, and alleviate NP. Understanding the intricate mechanisms of BoNT transport and its interactions with neuronal pathways provides valuable insights into its therapeutic potential for managing NP.

BoNT-A has been widely used in therapeutic and cosmetic practice, and therapeutic or cosmetic exposure to BoNT-A can provoke an immune response leading to formation of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs). These antibodies can bind to the toxin, blocking its biological activity, which results in a partial or complete loss of clinical effect. It has been suggested that a higher dosage and shorter interval of BTX-A may contribute to the NAbs formation [33].

BoNT immunogenicity is influenced by the following factors:

1) Selection of BoNT preparation. BoNT preparations differ in the presence of complexing proteins that may increase immune response. For instance, a complex protein-free incobotulinumtoxinA (incoA) preparation exhibits lower immunogenicity than other BoNT formulations. A meta-analysis of 61 studies on BoNT immunogenicity [34] suggests more prevalent nAbs across indications in patients treated with rimabotulinumtoxinB (rimaB; 42.4%), onabotulinumtoxinA (onaA; ≈1.5%) or abobotulinumtoxinA (aboA; ≈ 1.7%) compared with incoA (0.5%). This confirmed the low immunogenicity of incoA and low risk of secondary non-responsiveness (SnR) to treatment for patients receiving this BoNT formulation. Among secondary non-responders, nAbs were reported in 32.5% of those treated with onaA and 56.7% of those treated with aboA, but there were no patients with SnR to incoA. In addition, incoA was found to be effective even in the presence of NAbs (the above mentioned “0.5%”).

Of note, in pivotal trials supporting FDA approvals of BoNT formulations in clinical use, nAbs developed in patients all of whom had been pretreated with onaA or aboA [35].

2) Injection dose and frequency. In addition to avoiding booster injections of BoNT-A and providing short intervals between injections, reducing the individual injected doses may diminish the risk of NAb induction [36].

3) Indications for use. The risk of immunogenicity is higher in therapeutic applications than in cosmetic applications of BONT. This may be particularly relevant to therapeutic indications requiring a large total cumulative dose of BONT with frequent injections and larger dosage [33].

Postherpetic neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a disabling consequence of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. It is a chronic neuropathic condition that persists long after rash healing, substantially affecting QoL and posing a therapeutic challenge. Persistent burning pain, allodynia, and/or hyperalgesia at or near the area of the rash are characteristic of PHN. Symptoms may persist for years after primary infection. Traditional approaches to treatment of PHN include a combination of anticonvulsants, antidepressants and opioid analgetics. They, however, often do not provide adequate pain relief and commonly have substantial side effects, especially among elderly patients, who make up most of the population with PHN. This has led to interest in alternative therapeutic modalities, particularly BoNT.

A Pubmed search with the keywords “botulinum toxin” and “postherpetic neuralgia” keywords yields 56 publications, including 5 publications on results of clinical trials, 5 publications on RCTs, 21 literature reviews, 5 meta-analyses, and 7 systematic reviews.

Sotiriou et al [37] reported on 3 cases (two males and one female; mean age, 67 years) with severe PHN. The therapeutic procedure for all patients was as follows: dilution was made by adding 4 ml of sodium chloride to each sterile vial containing 100 units (U) of BoNT-A, resulting in a concentration of 25 U/ml. The solution was injected subcutaneously, in a chessboard fashion, over the affected area. The mean visual analogue scale (VAS) score dropped from 8.3 at baseline to 2 at the first follow-up visit (week 2). The mean duration of the analgesic effect of BoNT-A was 64 days. Mean VAS score increased to 4 and remained at that level at week 12.

Liu et al [38] reported a case of an 80-year-old man treated with BoNT-A for PHN. One hundred units of BoNT-A were injected subcutaneously in a fanning fashion in divided doses (20 routes in total, 5 U/route) into the area of allodynia. The VAS decreased from 10 to 1 gradually after 2 days and the effect lasted 52 days after the injection. After his pain increased again, ordinary medications (amitriptyline and gabapentin) were used to maintain his pain level at 3-4/10 on the VAS for 9 subsequent months. No side effect was observed.

Chen et al [39] conducted a single-blind RCT to compare the efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency (RF) and subcutaneous injection of BoNT-A in the treatment of PHN in 100 patients divided into two groups (n = 50 per group). A total of 100 units of BoNT-A was diluted with 4 ml saline (25 units/ml) and injected subcutaneously within the labeled area at an interval of 1.5–2 cm (0.1 ml for each site, i.e., 2.5 units of BoNT-A). The maximum dose was 200 units. A numerical rating scale (NRS) was used to score the pain, and a sleep quality questionnaire and anxiety and depression scales were used to assess sleep quality, and anxiety and depression, respectively, over 24 weeks. Pain scores and sleep quality scores of patients in both groups significantly improved compared to baseline at all time points, with no significant difference between the groups. BoNT-A showed better outcomes in terms of improvements in burning pain and anxiety, whereas RF, in terms of improvements in stabbing pain.

Apalla et al [40] performed a randomized, double-blind, single-dose, placebo-controlled trial to assess efficacy of subcutaneous BoNT-A injection in the management of PHN. Thirty patients (18 males and 12 females; age range, 73-77 years) with PHN were randomized either to BoNT-A or placebo. A total of 100 BoNT-A U (5 U/route), diluted with 4 mL sodium chloride, was injected subcutaneously in a chessboard manner, all over the affected area. Each patient received 40 injections in total, with a minimal distance of 1 cm between injection sites. Overall, 13 (87%) of BoNT-A patients achieved at least a 50% reduction in VAS pain score, compared with none of the placebo patients. The reduction was achieved within a week, and persisted for a median of 16 weeks. Additionally, the BoNT-A group showed a significant improvement in sleep quality.

Xiao et al [41] assessed the benefits of BoNT-A for the treatment of PHN in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sixty subjects (28 males and 32 females; age range, 42-84 years) with PHN were randomly and evenly distributed into BoNT-A, lidocaine, and placebo groups to receive subcutaneous injections of 5 u/mL BoNT-A, 0.5% lidocaine, or 0.9% saline, respectively. Volumes of administration varied according to the area of tactile allodynia, but less than 40-mL volumes (200 U for the maximum BoNT-A dose) were used. VAS pain, sleeping time hours and opioid usage were evaluated at the time of pretreatment and over 3 months post-treatment. VAS pain scores of the BoNT-A group decreased more significantly compared with two other groups at day 7 and 3 months (P < 0.01). Pain reduction began at days 3 to 5 after BoNT-A injection, increased to maximum effect at day 7, and remained stable for up to 3 months. A significant reduction in opioid use and increase in sleep time were observed in the BoNT-A group compared with two other groups.

Shackleton et al [42] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of a BoNT-A in treating trigeminal neuralgia (TN) and PHN. Six randomized, placebo-controlled trials published before April 16, 2014 were eligible for inclusion. Pooled results showed a difference in post-treatment pain intensity of -3 (as assessed by VAS) in favor of BoNT-A compared with placebo in managing TN or PHN. In the 3 studies that reported patients with at least 50% reduction in pain, patients treated with BoNT-A were 2.9 times more likely to achieve this compared with the placebo group. The overall strength of the evidence was moderate because of the relatively small number of studies, the risk of bias, and variation in dosage amount (20 U to 200 U) and exact location of the injection. The authors of [42] believe that, with the accumulation of more evidence, it may be prudent to think of BoNT-A not as a backup to other failed therapies but as a first-line approach to treating patients with TN or PHN.

Li et al [43] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of a BoNT-A vs lidocaine in treating PHN. Seven randomized control trials comprising 752 patients (367 BoNT-A patients and 385 lidocaine patients) published between 2005 and February 2019 were eligible for inclusion. The VAS pain score was significantly lower at 1, 2 and 3 months after treatment, the effective rate was significantly higher and scores on the McGill pain questionnaire were significantly lower in patients who received subcutaneous BoNT-A injection at the site of herpetic lesion for PHN compared to those who received lidocaine. There was no significant difference in the adverse event rate between these groups.

Ri et al [44] conducted a literature review of publications published before February 2020 and reported on 3 cases of PHN treated with BoNT-A. A total of 10 clinical trials and six case reports including 251 patients with PHN were presented. They showed that BoNT-A (onaA, aboA or incoA) therapy with injection intervals of 10–14 weeks resulted in significant pain reduction (up to 30–50%). The effect duration correlated with BoNT-A doses per injection site. Ri et al reported that they themselves used incoA at a dose per treatment session of 150 to 300 U over two years in three patients with PHN, which resulted in marked pain reduction and no adverse events. Despite different techniques using intra- or subcutaneous injections, the efficacy and safety of BoNT-A against PHN has been shown in all patients (even in two pregnant patients). In the case of onaA or incoA, Ri et al recommended the doses of 5-10 U per injection point, with the injection interval (10–14 weeks) decided individually. They concluded that BoNT-A seemed to be a good option for long-term management in severe PHN, especially when traditional oral medications have failed or are intolerable.

Halb et al [45] conducted a systematic literature search to provide an overview of the current evidence for the use of BoNT for PHN. Five case reports or series and 6 prospective studies published before February, 2020 were eligible for inclusion. The use of aboA was reported in one publication and the use of onaA, in most of the 11 publications. Injections were commonly performed in a grid-like pattern at doses of 2.5-15 U per injection point, with a total dose usually not exceeding 200 U. Intracutaneous and subcutaneous injection techniques were found to be effective in the management of PHN, but the former were more painful. Studies demonstrated a significant reduction in pain intensity and improvement in sleep quality in patients who received BoNT-A treatment for PHN, and the presence of mechanical allodynia and reduction in heat pain threshold were established as potential predictors of treatment success. Pain at the site of injection was the only substantial side effect noted.

Wang and Lin [46] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the efficacy and safety of a subcutaneous BoNT-A injection in the treatment of PHN compared to analgesics. Fourteen randomized controlled trials with 1358 Chinese subjects (670 BoNT-A subjects and 688 analgesic subjects) were included in the meta-analysis. BoNT-A (Lanzhou Biologic Product Institute, China; maximum dose, 100 U) was more advantageous compared to lidocaine or gabapentinin in VAS pain score reduction in PHN. Safety profiles were comparable between the groups, with no significant difference in adverse event rate. Wang and Lin concluded that further research was needed to draw definite conclusions on the efficacy of BoNT-A and dosage recommendations for PHN.

Given the positive results of clinical trials of BoNT in PNH, the relevant publications have been cited in numerous clinical guidelines on NP management. As early as 2010, such publications were cited in the European Federation of neurological Societies (EFNS) guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of NP [47] and the Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group (NeuPSIG) recommendations for the pharmacological management of NP [48]. The 2020 guideline on the diagnosis and non-interventional therapy of neuropathic pain of the German Society of Neurology [49] recommends that onaA can be considered for the treatment of NP of any etiology, but only as a third choice drug for focal limited pain, when conventional treatment options have failed or have caused significant side effects.

Recommendations. The above literature data indicate the promising efficacy of BoNT-A for PHN. Researchers have managed to obtain a substantial reduction in pain intensity after subcutaneous or intracutaneous BoNT-A injections, with this reduction lasting for months thereafter. This treatment demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with a major side effect being pain at the site of injection. The experience of the authors of the current consensus has generally confirmed these findings. In our point of view, however, the success rate of BoNT therapy is lower in patients with extremely severe VZV-associated pain persisting for years than in those with shorter disease duration.

In PHN, BoNT is injected subcutaneously or intradermally, covering the involved area of NP or allodynia in a grid-like pattern. The authors of the above reports commonly used BoNT-A at a standard dilution, 50 U/ cc or 100 U/ 2 cc, and less commonly at a double dilution, 100 U/ 4 cc (the dosage is specified for incoA and onaA). The authors of the current consensus commonly use BoNT-A at a standard dilution. The total BoNT-A dose administered to each patient per session depends on the affected area and ranges between 100 and 200 U. Based on our experience, we recommend to calculate the total dose on the basis of 2.5 U/ cm2 of skin.

Painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN)

Diabetic mellitus is a global pandemic that affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is one of the most common complications of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Up to half of patients with diabetes develop neuropathy during the course of their disease. Peripheral nerve injury in diabetes can manifest as progressive distal symmetric polyneuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, radiculoplexopathies, and mononeuropathies. The most common DN is distal symmetric polyneuropathy, with its characteristic glove and stocking like presentation of distal sensory or motor function loss. DN is usually characterized by a sensory disturbance involving the feet, which ascends to the calves over time, and, in more advanced cases, also eventually involves the upper limbs. Approximately 30–40% of patients with DN develop NP and thus are believed to have PDN. In PDN, pain results from peripheral nerve injury due to prolonged hyperglycemia. The pathological cause is axonopathy due to microangiopathy, ischemia and degeneration of neural sheaths. The pain is often described as a burning, pricking or lancinating sensation that increases in intensity at night, leading to sleep disturbances and a significant deterioration in the QoL. Associated symptoms may include painful sensation to touch (allodynia), impaired temperature sensation or abnormal sensations like pricking or numbness [50].

Management of PDN involves glycemic control, medication therapy with various classes of medications, particularly antidepressants (amitriptyline and duloxetine), gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin), and opioid analgesics, and physical rehabilitation. However, due to the lack of long-lasting analgesic effects and side effects, these drugs are often ineffective or not well tolerated. A systematic review and meta-analysis [51] concluded that intradermal BoNT-A injection is a promising alternative treatment for PDN pain.

Yuan et al [52] conducted a randomized double-blind crossover trial in 18 patients injecting onaA (50 U in each foot, 12 sites, 4 U/site, with the injection distributed across the dorsum of the foot) or saline intradermally in the hyperesthetic and allodynic foot regions. The BoNT-A treatment resulted in a significant reduction in pain VAS (≥ 3) and improvement in sleep quality during a 12-week period. In another blinded, placebo-controlled crossover study, Ghasemi et al [53] assessed the efficacy of BoNT-A in 40 patients with DPN. Totally, 100 U aboA in was administered intradermally into one foot, with each injection comprising approximately 8-10 U BoNT-A. The BoNT-A treatment resulted in a significant reduction in pain VAS and improvements in Douleur Neuropathique 4 Questions (DN4) questionnaire scores and neuropathy pain scale (NPS) scores. At 3 weeks, 35% and 30% of patients in the BoNT-A group showed bilateral pain reduction and no pain, respectively.

A comparative study [54] included 30 patients with type 2 diabetes (DM2) and aimed to compare BoNT-A with conventional oral treatment (200 mg carbamazepine twice a day) as a second-line treatment of PDN. Group 1 had add-on duloxetine 60 mg once daily, group 2 had add-on gabapentin 300 mg twice daily and group 3 had intradermal BoNT-A injections (50 U into each foot, evenly distributed equally in 10 injection sites). Assessments were performed through VAS and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) at baseline, 1 week, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks. Gaber and El Deeb [54] concluded that intradermal BoNT-A had a comparable if not superior efficacy to duloxetine and gabapentin as a second-line treatment of DPN.

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial [55] aimed to assess effects of BoNT-A injection on pain symptoms, QoL and sleep quality in DPN. Thirty patients with DM2 and DPN confirmed by DN4 and nerve conduction study (NCS) were included and randomized either to BoNT-A or placebo. In the BoNT-A group, 100 U aboA were dissolved in 1.2 ml normal saline and intradermal injections were distributed equally across the dorsum of the foot in a grid-distribution pattern over 12 sites (3 x 4 sites; as 0.1 ml (8.33 U) injection per site). BoNT-A patients showed a significant improvement in the mean VAS, PSQI, physical dimension of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), and some Neuropathic Pain Scale indices over 12 weeks after injections.

Muscle cramps occur in >50% of diabetic patients and reduce the QoL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled perspective study [56] aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of BoNT-A intramuscular injection for treating calf or foot cramps refractory to common pharmacological drugs. Fifty patients with DPN and cramps were included and randomized into two matched groups. IncoA (100 or 30 units) or saline was injected on each side into the gastrocnemius or the small flexor foot muscles. BoNT-A was efficacious in significantly reducing pain intensity and cramp frequency in 80% of the cases, with improvements maintained to week 14.

A large prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial [57] investigated the efficacy of BoNT-A on DPN. A total of 141 diabetics with polyneuropathy in lower limbs were randomly assigned to group D1 (150 U BoNT-A totally, 20 sites, 7.5 U/ site, in the sole of the right foot and normal saline 0.9% in the sole of the left foot), group D2 (75 U BoNT-A per foot, 20 sites, 3.5 U/ site, in the sole of each foot), and group N (normal saline 0.9% in both feet). BoNT-A was administered intradermally in a grid-distribution pattern (5 x 4) of 20 sites 1 cm apart. At 4 weeks, VAS pain score and NPS indices improved in BoNT-A treatment groups compared with controls.

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis on BoNT-A for DPN pain [51] found that BoNT-A treatment induced a greater reduction in VAS pain score, and improved several NPS items (e.g., hot sensation, unpleasant sensation, deep pain, and surface pain) significantly more than placebo treatment. In addition, there was no significant difference in adverse effects between BoNT-A and placebo.

A 2024 Systematic Guideline by the American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN) Workgroup on the Evidence, Education, and Treatment Algorithm for PDN [58] noted that few studies have demonstrated optimistic results utilizing BoNT-A injection for PDN without major complications. Numerous studies found that BoNT-A can reduce NP intensity and improve the QoL of patients with PDN. BoNT-A injections should only be considered as an adjunctive treatment to first-line modalities [58].

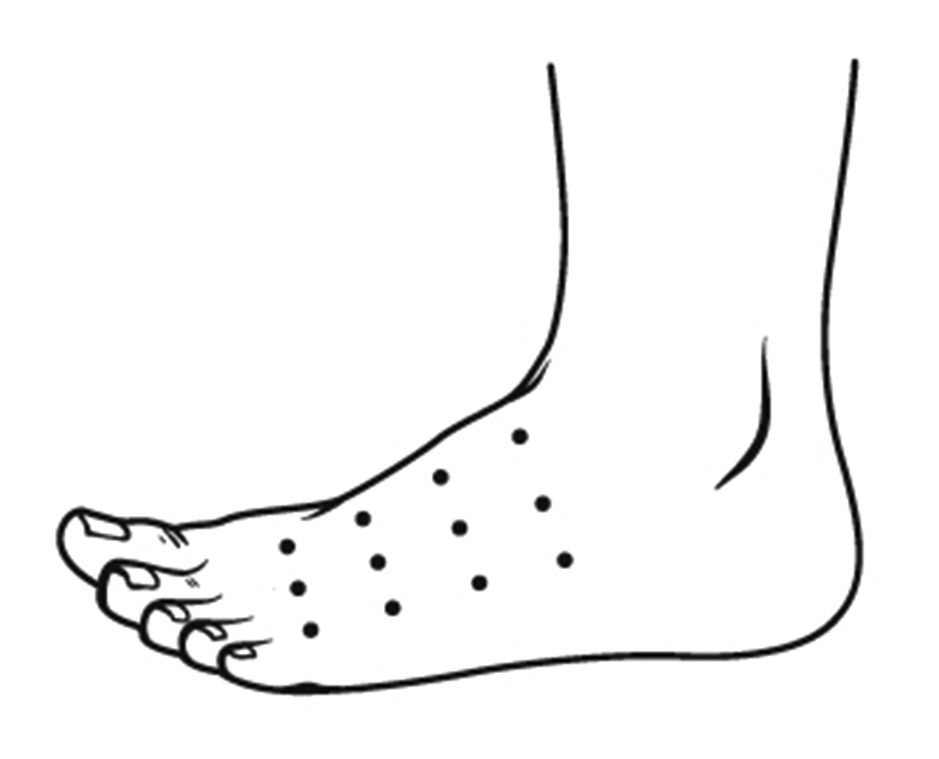

Recommendations. Based on the results of studies, BoNT-A may be considered as an adjunctive treatment for PDN to first-line modalities. In patients with a typical location of PDN (i.e., the dorsum of the feet), it is recommended to inject 50 U BoNT-A into one foot (the dosage is specified for incoA and onaA). The total dose is usually distributed in a grid-distribution pattern over 12 sites (3 x 4 sites; about 4 U /site) (Fig. 1). The authors of most studies and of a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis recommend intradermal BoNT injections for PDN. However, the authors of some studies and the consensus believe that subcutaneous BoNT injections may be not less effective than intradermal BoNT injections for PDN. For the convenience, we recommend using BoNT-A at a standard dilution (50 U/ cc or 100 U/ 2 cc). The dose may be increased for large affected areas (we recommend to calculate the dose on the basis of 2.5 U per cm2 of skin). The expected average duration of pain relief after BoNT-A for PDN is 12 weeks. However, according to the observations of A.I. Gavretskyi, a co-author of the current consensus, there was no pain recurrence at five-year follow-up after BoNT-A injections into a limited area of acute burning or lancinating pain in the foot in several patients.

Fig. 1. Typical grid-distribution pattern for intradermal BoNT-A injection for PDN, with a total dose of 50 U distributed over 12 sites (3 x 4 sites; about 4 U per site). The dosage is specified for incoA and onaA.

Trigeminal neuralgia

TN is a debilitating neurological condition with brief attacks of facial pain restricted to the trigeminal distribution and with and electric shock-like shooting, stabbing, or sharp quality. TN-associated pain is one of the most severe pains known, often referred to as “suicidal”, and is triggered by innocuous stimulation of the face and intraoral mucosa such as touching the face, talking chewing, drinking, washing the face, shaving, etc.

TN can be classified as classical, secondary or idiopathic. The classic type accounts for 75% of cases and is diagnosed when there is nerve root atrophy and/or displacement due to trigeminal neurovascular compression (NVC) identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or intraoperatively. Secondary TN is more closely associated with MS or mass lesions. The presence of a demyelinating lesion at the trigeminal root entry zone or in the pons is a diagnostic criterion of TN attributed to MS. Idiopathic TN is diagnosed when no underlying disease can be found.

The first-line treatment for TN is pharmacological, with carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and/or baclofen used to prevent TN attacks. Surgery should be considered if the pain is poorly controlled, or the medical treatments are poorly tolerated. Trigeminal vascular decompression removes the NVC and is the surgery of first choice in classic TN. Other surgical treatment options include percutaneous neuroablative techniques and Gamma Knife stereotactic surgery.

A Pubmed search with the keywords “botulinum toxin” and “trigeminal neuralgia” keywords yields 160 publications, including 13 publications on results of clinical trials, 8 publications on RCTs, 57 literature reviews, 9 meta-analyses, and 17 systematic reviews.

The largest studies on the efficacy of BoNT-A in TN included an open-label trial of 100 TN patients [59], a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of 42 TN patients [60], a single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of 20 TN patients [61], a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of 36 TN patients [62], a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study comparing 2 doses of BoNT-A in 84 TN patients [63], and an open-label clinical trial of 88 TN patients with 14-month follow-up after BoNT-A [64].

In all studies, patients received BoNT-A at a dilution of 50 U per 1 or 2 cc, or 100 U per 2 or 4 cc saline (the dosage is specified for incoA and onaA).

In a study by Li et al [64], a total dose of 25-170 U BoNT-A was injected in the facial area and the trigger points of pain (15–20 injection sites, 15 mm apart, 2.5-5 units per point), at a depth of 0.5 cm. In addition, some patients with pain within one side of the gum received submucosal injections. In a study by Zhang et al [59], patients in the single-dose group received a total dose of 70-100 U BoNT-A, whereas the repeated-dose group received an initial dose of 50-70 U BoNT-A plus an equal dose 2 weeks later. The injections were administered intradermally, submucosally, or both. There were 15–25 injection sites, 15 mm apart, 2.5-5 U/ site, at a depth of 0.1 cm. In a study by Wu et al [60], eligible patients were randomized to receive BoNT-A (75 U, 15 injection sites, 5 U/ site) or placebo in the dermatome and/or mucosa (if the oral mucosa was involved) where pain was experienced. In a study by Shehata et al [61], eligible patients were randomized to receive onaA (40-60 U, 8-12 injection sites, 5 U/ site) or placebo. “Follow the pain” injection strategy was used, especially in the trigger zones. In patients with mandibular root involvement, a larger dose of the toxin was injected posteriorly in the masseter to avoid undesired cosmetic effectsIn a study by Zúñiga et al [62], patients were randomized to receive 50 U onaA or placebo (0.9% saline) subcutaneously in sites 1 cm apart. Cases with involvement of the 3rd trigeminal nerve also received intramuscularly either 10 U onaA or matching placebo in the masseter muscle, ipsilateral to the pain location. In a study by Zhang et al [63], patients were randomized to receive placebo, 25 U BoNT-A or 75 U BoNT-A at 20 points in the dermatome and/or mucosa (if the oral mucosa was involved) where pain was experienced.

In all the above studies, BoNT-A treatment resulted in a significant reduction in frequency and intensity of pain (the primary outcome measure was 50% or more reduction in pain as defined by VAS). A reduction in medication use was also noted. Pain relief was observed at 1 week.

In a study by Li et al [64], the positive treatment effect lasted for 3 months in most patients. Thereafter, the therapeutic effect decreased gradually, and the prevalence of effective treatment and complete pain control at 14 months was 38.6% and 25%, respectively. The positive treatment effect lasted in most patients about 4 months in a study by Zhang et al [59], the entire 12-week follow-up in a study by Shehata et al [61], 8-week follow-up in a study by Zhang et al [63], and 110-day follow-up in a study by Zúñiga et al [62].

According to the observations of V.V. Biloshytsky, a co-author of the current consensus, a 50-U incoA dose injected subcutaneously in the symptomatic area along a trigeminal nerve branch in a patient with TN can result in complete cessation of pain attacks and no need for preventive oral medications for as long as 7-8 months. Hosseini et al [65] reported on 3 TN patients in whom a significant improvement in pain lasted 2 years after incoA injection.

Most publications on the use of BoNT-A injection for TN reported on its efficacy. The treatment was well tolerated with no systemic side effects or serious adverse effects seen. Possible side effects include swelling, hematoma, itching or pain at the site of injection, facial asymmetry and transient masseter weakness. All side effects are temporary, do not interfere with a patient’s activities, and do not require special treatment.

The results of high-quality studies have provided the basis for including BoNT therapy in the most recent guidelines on TN management, e.g., the 2019 European Academy of Neurology guideline on TN [66] and the 2021 Royal College of Surgeons of England Guidelines for the management of TN [67].

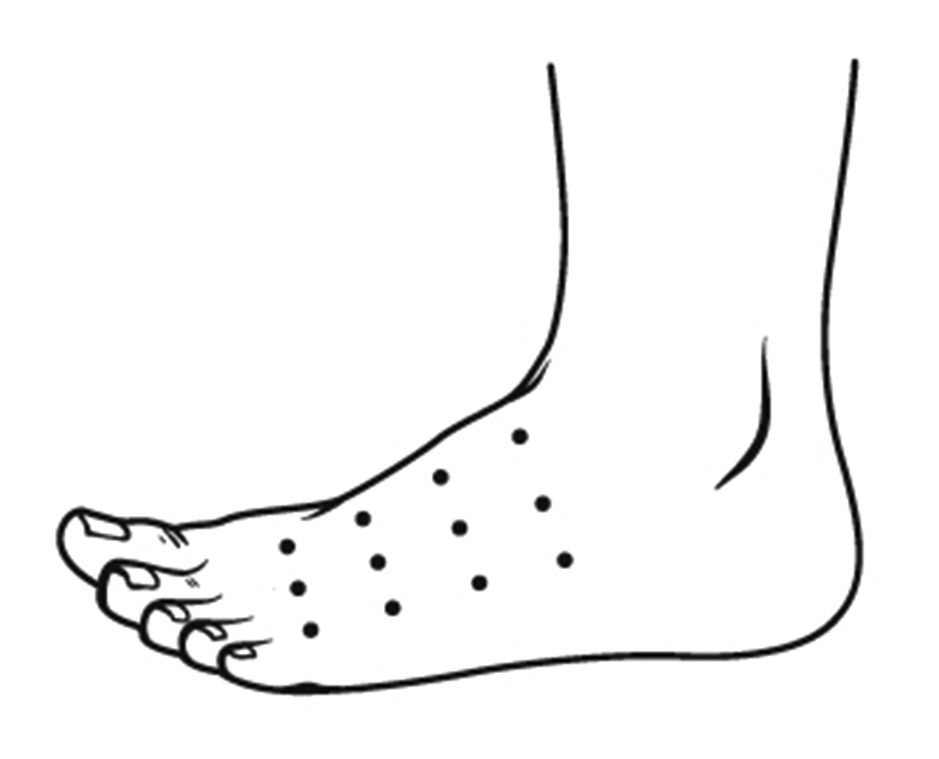

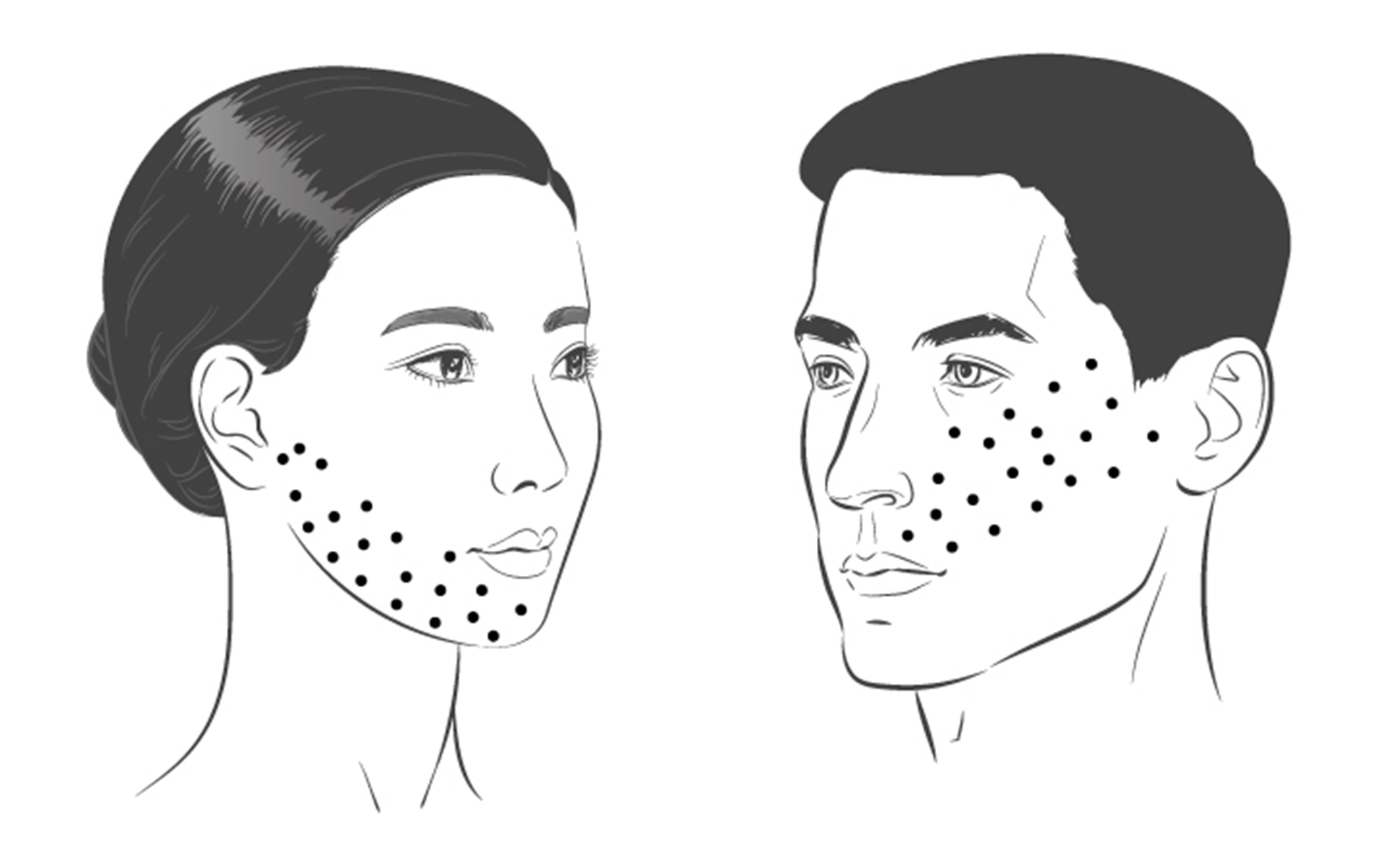

Recommendations. Based on the literature data and observations by the authors of the consensus, BONT-A injection can be recommended for treating TN when traditional medications have failed or are intolerable. BoNT-A is injected subcutaneously or intradermally at a total dose of 25-75 U, 2.5-5 U/ site (the dosage is specified for incoA and onaA). Our experience indicates that a total dose of about 50 U BoNT-A is effective in pain occurring in the distribution of one trigeminal nerve branch (Fig. 2). The total dose should be distributed across the symptomatic area (the painful area within the distribution of relevant trigeminal nerve branches), with a potential reduction in the distance between adjacent injection sites at the locations of pain trigger points in the skin. Submucosal injections can be performed in the presence of pain trigger points in the oral cavity. The doses should be adjusted according to the size of the symptomatic area, appearance od any adverse reactions, and patient response. BoNT-A injection to some sites on the contralateral side should also be considered to reduce facial asymmetry. Although evidence regarding the most appropriate frequency of infiltration is inconclusive, a minimum period of 12 weeks between cycles seems a reasonable approach [68]. In addition, a repeat injection session may be scheduled based on the recurrence of pain attacks.

Fig. 2. Possible patterns for intradermal BoNT-A injection for TN, with a total dose of 50 U distributed over 20 sites (about 2.5 U per site). Patterns of injection for pain in the V3 and V2 distributions of the trigeminal nerve are shown on the left and right sides of the figure, respectively. The dosage is specified for incoA and onaA.

Post-amputation pain

Post-amputation pain (e.g., phantom limb pain (PLP) and residual limb pain (RLP)) is related to a wide range of complaints associated with a loss of limb.

PLP places a significant emotional and physical burden on amputees and is a challenge for those treating them. It is characterized by painful sensation or disesthesia in a limb that is no longer present (deafferentation). It is important to distinguish PLP from other amputation sequelae, including non-painful phantom sensation, telescoping (a progressive sensation resulting in the distal limb being perceived more proximally), and stump pain (RLP, commonly localized to distal existing body part). If patients suffer from PLP, the onset is usually amputation secondary to trauma or surgical intervention [69]. PLP is a chronic NP. Although there are still many questions as to the underlying mechanisms, pathological morphological, physiological and chemical changes in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and CNS (particularly, spine and brain) seem to be involved. Peripheral mechanisms include inflammation and release of pronociceptive factors that cause a reduction in nociceptive thresholds, spontaneous activity of nociceptive pathways and increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system with the formation of neuromas due to the disorganized growth of damaged nerve terminals at the site of injury. Spinal mechanisms involve central sensitization which is mediated by the release of glutamate, substance P, and neurokinins from afferent Aδ- and C fibers. These neuromediators decrease the activation threshold of N-methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptors and increase neuronal sensitivity, leading to hypersensitivity in the spine segments adjacent to deafferentiated regions, which is manifested by pain in relevant body areas. Supraspinal changes related to PLP involve the brainstem, the thalamus and the cortex, with a reduction in the cortical representation of the lost limb, and expansion in the cortical representation of adjacent body parts [69, 70, 71].

Because the results of pharmacological interventions for treating PLP are not always satisfactory, developing new treatment methods for this condition is important. Published studies on the use of BoNT in PLP are case reports and series and results of isolated clinical trials. The results of these studies, however, indicated a substantial clinical effect of BoNT for PLP.

Kern et al [72] were the first to report on the subject in 2003. They injected 100 U BoNT-A (4×25 U in 0.5 ml saline 0.9%) in four muscle trigger points of the amputation stump in each of 4 amputees with PLP. VAS score dropped by 60–80% in all cases. The three patients, who had pain attacks, reported a 90% reduction in the number of attacks, and sleep disorder disappeared in both affected patients within 2–3 weeks. In a 2004 case report, Kern et al [73] reported the results of a 12-month follow-up of an amputee with PLP who had BoNT-A (4×25 U in 0.5 ml saline 0.9%) injected into trigger points of the stump muscles. With four injections performed every 3 months, the patient became almost completely pain-free, and his intrathecal morphine therapy could be reduced to 40% of the initial dose. Intrathecal clonidine was eliminated completely, as were the oral analgesics. In a 2024 case series by Kern et al [74], patients who had previously undergone amputation of the arm (n = 2) or leg (n = 2) were treated with BoNT-B injections at several trigger points of their stump musculature. The authors administered a total dose of 2500 U BoNT-B to the arm amputation stumps, 5000 U for one amputation of the lower leg, and 2500 U to the other lower leg amputation of a patient with a very low baseline body weight. All patients experienced a reduction in stump pain, which lasted as long as 3 months. Other reports included a reduction in the frequency of pain attacks, improvement in stump allodynia, and decreased occurrence of involuntary stump movements. In addition, night sleep quality significantly improved in one patient.

In a case series by Jin et al [75], 3 patients with PLP and stump pain who had previously undergone amputation of the leg below the knee (n = 2) or above the knee (n = 1) were treated with aboA injections at a total dose of 200 U, 300 U and 500 U, respectively, into points with strong fasciculation. VAS decreased from a pre-treatment value of 9-10, 7-10, and 6-8, respectively, to 0-2, 1-3, and 1-2, respectively, at 1-4 days, and treatment response lasted for up to 11 weeks. All patients rated the general clinical improvement as marked. Biloshytsky and Biloshytska [76] used incoA for treating PLP in two below-knee amputees following blast injury and reported treatment outcomes similar to those reported by Jin et al [75]. The first patient received subcutaneous incoA at a total dose of 160 U (32 sites, 3.5 U/ site). The second patient had trigger points in the stump muscles, and received subcutaneous incoA into the trigger points at a total dose of 240 U (6 sites, 40 U/ point). Elavarasi and Goyal [77] reported on successful BoNT-A treatment for PLP in an above-elbow amputee. The patient received 200 U (2.5 U per cm2) of onaA in the distal surface of the end of the amputation stump. At 10 days, the VAS score improved from 8-9 to 1-2, and the benefit lasted 10 weeks.

A prospective randomized double-blinded pilot study [78] aimed to examine the effect of BoNT-A (onaA) injection versus Lidocaine/Depomedrol injection on RLP and PLP in 14 patients. An injection dosage of 1 mL, equal to 50 U BoNT-A was used for each injection site, with total units ranging from 250 to 300 U. Both BoNT-A and Lidocaine/Depomedrol injections resulted in immediate improvement of RLP (not PLP) and pain tolerance, which lasted for 6 months.

Intradermal BoNT injections were found to be effective for such a common sequela of amputation as residual limb hyperhidrosis (RLH). Positive treatment outcomes were reported in a series [79] of 9 lower-limb amputees who received injections of 1750 U BoNT-B for the treatment of RLH (20 intracutaneous injections each) and a series [80] of 8 unilateral upper- or lower-limb amputees in whom 300–500 U of onaA was injected intradermally at 2 to 3 U a site and in a circumferential manner at 1-cm intervals in a grid pattern within the area covered by the amputee’s socket, except for those with transfemoral amputations, where the distal part of the residual limb was injected. In the former series, patients reported on a significant improvement of stump pain 3 months after injection.

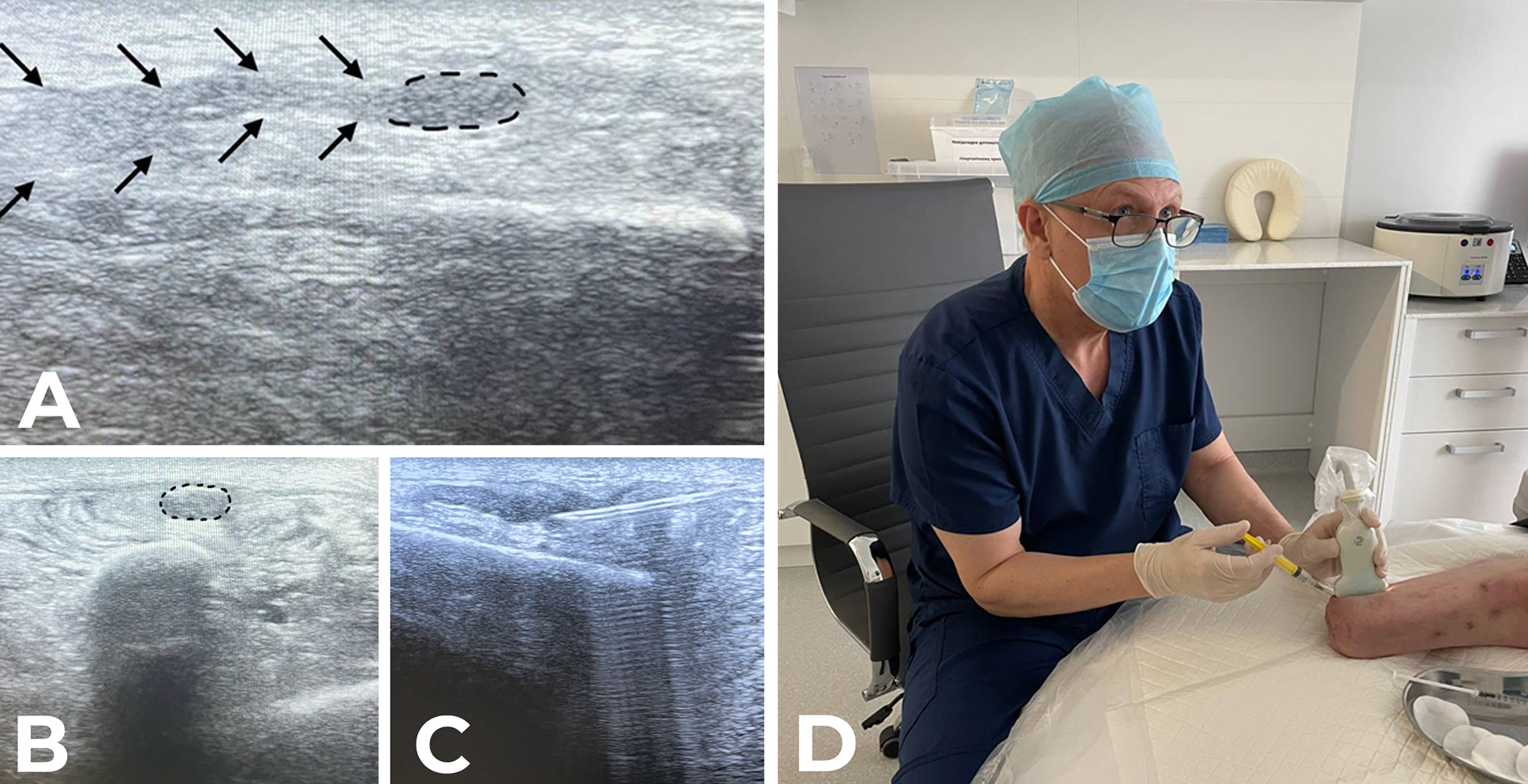

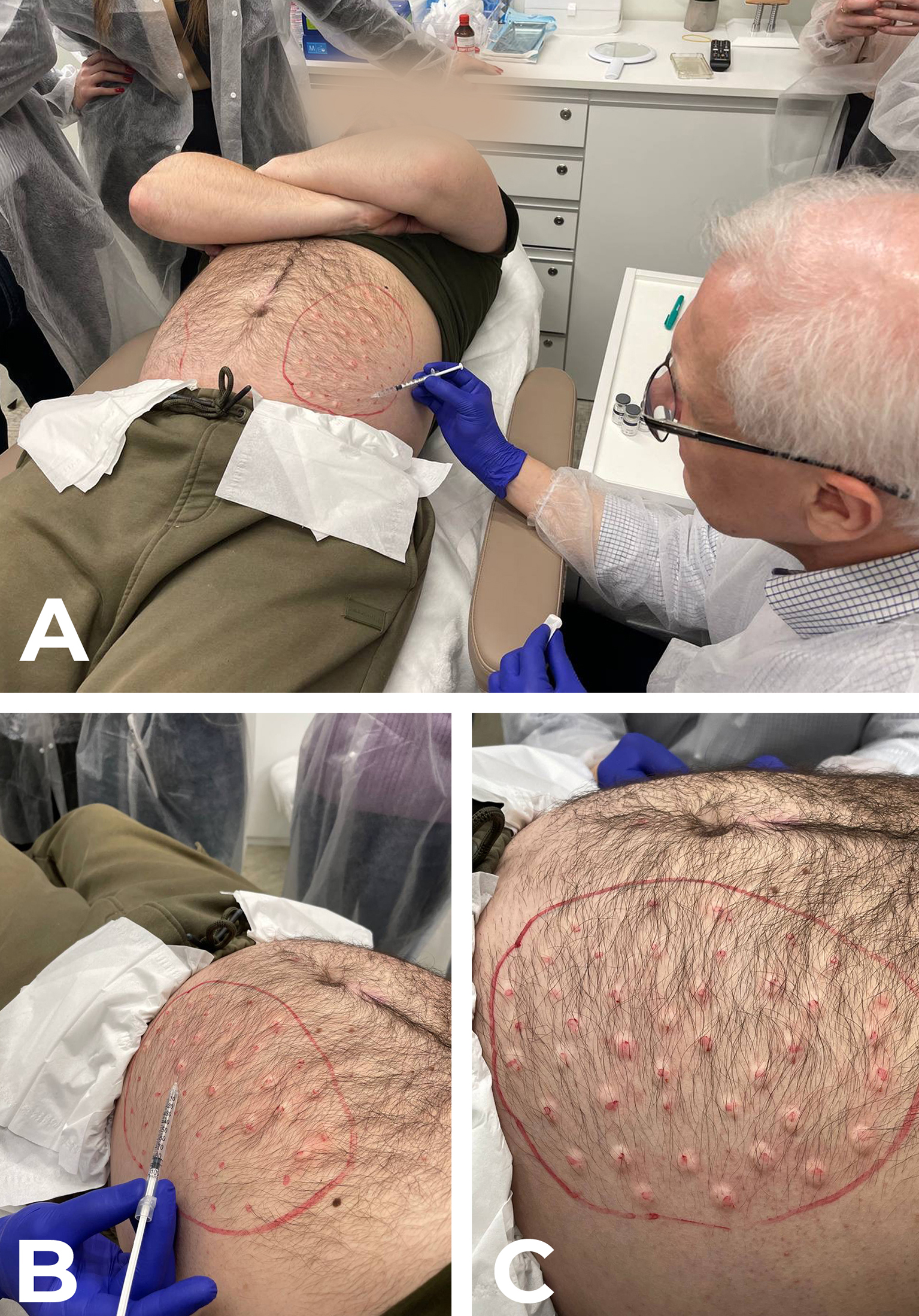

Recommendations. The above literature and the experience of the authors the consensus (M.V. Biloshytska, V.V. Biloshytsky, D.V. Dmytriiev, N.T. Segin and A.V. Filipskyi) indicate that BoNT-A can be an effective treatment for PLP and/or stump pain when either the pain is resistant to medical treatment or the latter is poorly tolerated due to side effects. In our opinion, when combined with pharmacological therapy and physical therapy, BoNT therapy enables prolonged pain relief outcome in many cases. Given large numbers of amputees with pain in Ukraine, the experience accumulated enables selecting the most appropriate injection technique for each set of clinical data. In a stump without trigger points, it seems most appropriate to perform intradermal or subcutaneous injections in the distal part of the residual limb (most publications on BoNT therapy for NP favor the use of intradermal injections). The total dose of BoNT-A injected can range from 100 to 200 U for the residual upper limb or below-knee amputation residual limb, and be as large as 200-300 U for the above-knee amputation residual limb (here and below, the dosage is specified for incoA and onaA). A typical recommendation for BoNT-A dose for NP (2.5 U per cm2 of skin) can be helpful for drug distribution over the skin surface. If muscular trigger points are identified by stump palpation-evoked referred pain (particularly, PLP attacks), BoNT injection can be performed in these trigger points (30-50 U BoNT-A per trigger point). Our experience has demonstrated that, in the presence of ultrasound evidence of amputation neuroma, ultrasound-guided BoNT-A injection into the neuroma may be reasonable (Fig. 3). In our observations, the average dose of incoA injection dose per neuroma was 40-50 U. According to the observations by N.T. Segin, a co-author of the current consensus, better results of intraneuromal BoNT-A injection were observed in cases with (a) no involvement of the amputation neuroma in scar tissue or (b) no neuroma-to-bone contact causing severe irritation. It should be remembered that trigger point injection or neuromal injection is a painful procedure and may require patient sedation.

Fig. 3. 50-U incoA injection in the neuroma of the superficial peroneal nerve. A: US scan of the long axis of the nerve. Arrows point to the nerve and the dotted line surrounds the neuroma. B: Transverse US scan of the stump neuroma. Dotted line shows the hypoechoic shadow of the neuroma. C, D: Ultrasound-guided intraneuromal injection of incoA.

Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic disorder characterized by a continuing (spontaneous and/or evoked) regional pain that is seemingly disproportionate in time or degree to the usual course of any known trauma or other lesion. The pain is regional (not in a specific nerve territory or dermatome), and is usually accompanied by edema and abnormal sensory, motor, sudomotor, and/or vasomotor findings. Although a portion of CRPS patients recover within 12 months, most patients suffer from severe allodynia and loss of work capacity.

The syndrome frequently develops after trauma, but sometimes may be idiopathic. CRPS has been subdivided into reflex sympathetic dystrophy (CRPS-1) or causalgia (CRPS-2). CRPS-1, or reflex sympathetic dystrophy, accounts for 90% of cases, and occurs after an illness or injury that didn’t directly damage the nerves in the affected limb. Confirmation of nerve injury on nerve conduction testing is the defining feature of CRPS-2. The underlying mechanism has been traditionally believed to involve peripheral and central sensitization that develop due to neurogenic inflammation and sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, e.g., hypersensitivity of adrenergic receptors whose stimulation results in increased release of nociceptive mediators. Impaired inhibition of the dorsal horns by the brainstem also plays an important role.

CRPS is diagnosed by the Budapest Criteria:

1) Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event

2) Must report at least one symptom in three of the four following categories:

Sensory: Reports of hyperalgesia and/or allodynia

Vasomotor: Reports of temperature asymmetry and/or skin color changes and/or skin color asymmetry

Sudomotor/Edema: Reports of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

Motor/Trophic: Reports of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

3) Must display at least one sign at time of evaluation in two or more of the following categories:

Sensory: Evidence of hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch and/or deep somatic pressure and/or joint movement)

Vasomotor: Evidence of temperature asymmetry and/or skin color changes and/or asymmetry

Sudomotor/Edema: Evidence of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

Motor/Trophic: Evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

4) There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms

Although various approaches to CRPS management have been advocated, the disease is still challenging to manage, and prognosis is usually poor.

Kinesitherapy, physical therapy and pharmacological therapy (oral corticosteroids, ketamine infusion, and anesthetic sympathetic blockade) have been recommended; electrical stimulation of the spinal cord has been recommended in incurable CRPS patients [81, 82, 83].

A Pubmed search with the keywords “botulinum toxin” and “complex regional pain syndrome” keywords yields 63 publications, including 4 publications on results of clinical trials, 3 publications on RCTs, 26 literature reviews, 1 meta-analysis, and 2 systematic reviews, and many case reports on successful BoNT treatment for CRPS.

Bellon et al [82] reported on a case of upper left arm CRPS-1 which developed 3 years after a traumatic acromioclavicular subluxation and was followed by initial treatment with surgical reduction. The patient referred sub-continuous pain disproportionate to trigger, associated with hyperesthesia, erythema, an increase of cutaneous temperature, an increase in sweating and a reduction of left shoulder’s range of motion (ROM) which poorly responded to conservative treatment and rehabilitative measures. Symptoms improved after 100 U incoA was injected into the glenohumeral joint through a posterior access.

Sáenz et al [84] reported a case of a man with a history of cardiac surgery who manifested bilateral pectoralis major stiffness, bilateral shoulder pain and a reduction in the glenohumeral joint ROM which was diagnosed as a manifestation of CRPS-1. The condition responded neither to rehabilitation nor to oral medication, but significantly improved after the left and right pectoralis major muscles were injected with 50 U and 75 U, respectively, of BoNT-A at 5 points each.

Fallatah et al [85] used interscalene brachial plexus block in the treatment of a 34-year-old female patient who developed upper limb CRPS-1 without any apparent reason. Two weeks later, after recurrence of her neck pain, she received 100 U BoNT-A injected into trigger points of the trapezius muscle, which contributed to complete pain relief with full recovery of limb function.

Tombak et al [86] described a case of CRPS-1 in a 53-year-old woman which developed after a distal radius fracture and was characterized by severe allodynia, swelling and autonomic changes in the left hand resulting in contracture of the left hand muscles. An improvement in the hand ROM and grip strength was seen after treatment with injection of BoNT-A into the hand muscles (10 points). Improvements in pain were observed in 4 patients with “dystonic clenched fist” associated with CRPS [87] after they received aboA injections into lumbrical, flexor pollicis brevis, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and adductor pollicis. Target muscles and doses for BoNTA injections depended on the clinical situation of the patient.

Safarpour and Jabbari [88] reported on two cases of CRPS-1 with the development of trigger points in the proximal muscles and myofascial pain syndrome in the proximal right arm, shoulder girdle and neck after surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome (case 1) or following a traumatic forearm injury due to the hand stuck in a bus door (case 2). CRPS was resistant to medication treatment, but responded well to BoNT-A injections in the trigger points (20 U/point) in both cases. BoNT-A was injected into 10 trigger points in the right trapezius, rhomboid, levator scapulae and right flexor digitrum superfecialis in patient 1 and 12 trigger points in trapezius, splenius capitis and rhomboid muscles in patient 2.

Plastic surgeons [89] described a case of CRPS-2 in a man, which developed after undergoing surgery for a crush injury to the distal phalanx of his right third digit. Forty-five days postoperatively, he presented with severe allodynia and paresthesia. Treatment with medications was ineffective. Symptoms improved after a subcutaneous injection of 10 U onaA was distributed among 5 sites at the base of the digit.

Birthi et al [90] reported a case of a nurse who had an 11-year history of left upper arm CRPS-I that developed after lifting a heavy patient and was refractory to multimodal and standard pain therapies. Her symptoms improved after she underwent subcutaneous injection of 100 U BoNT-A at 20 sites (5 U/site, 10 cm apart) on the dorsum of the left hand, proximal and distal phalanges.

Kharkar et al [91] conducted a retrospective chart review of 37 patients with spasm/dystonia in the neck and/or upper limb girdle muscles who had CRPS as their primary diagnosis. Electromyography (EMG)-guided injection of BoNT-A, 10-20 U per muscle was used. Total dose used was 100 U in each patient. By Farrar’s criterion (i.e., a decrease in local pain score by 2/10 or more points), 36/37 patients (97%) reported significant improvement in local pain 4 weeks after BoNT-A injections.

Several small studies assessed the hypothesis that BoNT would prolong analgesia after sympathetic blocks in patients with lower limb CRPS. The hypothesis was based on the fact that pre-ganglionic sympathetic nerves are cholinergic, and BoNT has been found to inhibit the release of acetylcholine at the cholinergic nerve terminals. Carroll et al [92] compared the duration of standard lumbar sympathetic block (LSB) with bupivacaine to LSB with bupivacaine and 75 U BoNT-A in 9 patients with refractory CRPS. LSBs were accomplished in standard fashion using intermittent fluoroscopy to place the tip of a single 22-gauge needle at the anterolateral border of the second lumbar vertebrae. Median time to analgesic failure was 71 days after LSB with BoNT-A compared with fewer than 10 days after standard LSB. Lee et al [93] found that BoNT-B was more effective than BoNT-A to prolong the sympathetic blocking effect in CRPS patients (13 patients and 5 patients, respectively). Choi et al [94] performed LSB (with levobupivacaine 0.25% 5 mL plus 5000 U BoNT-B injected at the L3 level under fluoroscopic guidance) in two lower-limb CRPS patients and found that BoNT-B can produce an efficacious and durable sympathetic blocking effect in such patients. Yoo et al [95] performed an RCT to investigate the clinical outcome of BoNT-A for LSB at L2 or L3 in 48 lower-limb CRPS patients. 8 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine and 75 U BoNT-A (Nabota, South Korea) mixed with 8 ml of nonpreserved saline solution were injected in the patients in the control and BoNT-A groups, respectively. In CRPS patients, LSB using BoNT-A increased the temperature of the affected foot for 3 months and reduced the pain [95].

A systematic review by Almeida et al [81] concluded that BoNT shows promise in alleviating pain associated with CRPS, particularly when used as an adjunct to LSB. However, the limited number of studies and small sample sizes impede reaching definitive conclusions regarding its efficacy and safety. Notably, local applications (intradermal or subcutaneous) require further investigation, as current evidence is insufficient. While preliminary findings suggest potential benefits of BoNT-A in managing CRPS, larger randomized trials are necessary to confirm its efficacy and safety [81].

Recommendations. Studies reporting on the opportunities of BoNT application in the treatment of CRPS involve small sample sizes and consider a variety of approaches (intracutaneous, subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intrajoint injections, lumbar sympathetic block with BoNT). These studies, however, have reported that improvement in CRPS can be achieved in patients resistant to conventional therapy. In addition, they noted the safety of BoNT-A injections and the absence of serious adverse events. This is in agreement with observations by the co-authors of the consensus (V.V. Biloshytsky reported an improvement in CRPS symptoms after subcutaneous BoNT-A injection). We believe that BoNT is a reasonable off-label option for severe CRPS refractory to conventional treatment modalities. Expected outcomes and evidence level should be explained to patients or their legal representatives, and this fact should be mentioned in the informed consent. Clinical features (presence of cutaneous allodynia, trigger points, dystonia of muscles, etc.) should be taken into account when selecting the appropriate injection technique (subcutaneous and/ or intradermal injection, intramuscular injection, etc.). The BoNT dose can be calculated based on the above literature data.

Piriformis syndrome

Piriformis syndrome (PS) is a compressive neuropathy that presents as pain, numbness, paresthesias, and weakness in the distribution of the sciatic nerve. It is caused by compression of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle as it passes through the sciatic notch. The piriformis muscle’s primary function is to rotate the femur externally at the hip joint. With internal rotation of the femur, the tendinous insertion and belly of the muscle can compress the sciatic nerve. If this compression persists or if spasm of hypertrophy of the muscle occurs, this can cause entrapment of the nerve. The syndrome is characterized by sciatica symptoms, and may account for as much as 6%-8% of patients seen for a complain of sciatica. Patients typically complain of intense unilateral pain in the buttock that may radiate to posterior aspects of the leg and worsen after prolonged sitting. They may develop an altered gait, leading to coexistent sacroiliac, back, and hip pain that confuses the clinical picture. Physical findings include limitation of straight-leg raising (Lasègue’s sign), tenderness over the sciatic notch and positive provocative (Freiburg, Pace, and Flexion, Adduction and Internal Rotation (FAIR) tests. Symptoms can be reproduced with these tests which place the sciatic nerve on stretch. Electroneuromyography (EMG) allows for the differentiation of PS from lumbosacral radiculopathy. MRI of the pelvis may show piriformis muscle atrophy or hypertrophy, a split or flattened sciatic nerve, and abnormal signal intensity of the nerve at the level of sciatic notch. Treatment options include physical therapy, analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetic, steroid and BoNT injections. Rarely, surgical release of the entrapment is required to obtain relief. Injection of local anesthetics into the piriformis muscle can serve both diagnostic and therapeutic [96, 97].

A Pubmed search with the keywords “botulinum toxin” and “piriformis syndrome” keywords yields 56 publications, including 10 publications on results of clinical trials, 3 publications on RCTs, 26 literature reviews, 1 meta-analysis, and 4 systematic reviews.

In a pilot, double-blind, single group, crossover study [98], 9 women with PS received a fluoroscopic/ EMG guided unilateral intramuscular piriformis injection with 100 U BoNT-A. VASs were used to measure pain intensity, distress, spasm, and interference with activities. Pain relief, as measured by VAS, occurred to a greater extent after intramuscular BoNT-A compared with similar injections with vehicle alone.

In a prospective, single-site, open-label trial [99], 20 patients with PS resistant to conventional therapy received a computed tomography (CT)-guided unilateral intramuscular piriformis injection with 150 U aboA. Pain was rated with a numeric rating scale and health-related QoL was assessed with the Korean version of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). It was concluded that a low dose of BoNT-A relieved pain and improved quality of life in patients with refractory PS.

A single-centre, randomised trial [100] compared the effects of CT-guided 100-U unilateral intramuscular injection with the intramuscular methylprednisolone in 40 patients suffering from chronic myofascial pain in the piriformis, iliopsoas or scalenus anterior muscles. Thirty days after receiving an injection of either BoNT-A or steroid followed by post-injection physiotherapy, pain severity had decreased significantly from baseline in both treatment groups (with no significant difference between the groups), but the reduction in pain score was greater in the BoNT-A group compared with the steroid group. At 60 days post-injection, the pain severity score for the BoNT-A-treated patients was statistically significantly lower than that for the steroid-treated patients. These results indicate the superior efficacy of BoNT-A over conventional steroid treatment in patients suffering from myofascial pain syndrome, when combined with appropriate physiotherapy.

A large open-label prospective study [96] aimed to devise a clinical assessment score for PS diagnosis and to develop a treatment strategy, and involved 250 PS patients. First-line treatment for PS consisted of muscle relaxants and massage-physiotherapy to allow daily self-rehabilitation and three physiotherapy sessions per week. Of 250 PS patients, 122 were unresponsive to the initial treatment, and received either one or two EMG-guided intramuscular piriformis injections of onaA spaced 3 months apart at a total dose 50-100 U, which improved symptoms and contributed to a positive rehabilitation outcome.

A 2011 evidence-based review [101] reported that, Level B evidence existed for the use of BoNT-A for treatment of refractive pain in PS (Recommendation: Probably Effective, Should Be Considered for Treatment).

Other studies [102, 103, 104] on the efficacy of BoNT for the treatment of PS were considered in detail in a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis [105] that aimed to investigate the efficacy of BoNT, local anesthetics (LA), and corticosteroid (CS) injections in relieving pain in PS patients. A systematic search was conducted through PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, and Scopus through April 2021 for studies investigating the efficacy of BoN, LA, or CS injection in improving pain in PS patients. Sixteen studies were included in the systematic review, and 12 of them were included in the quantitative synthesis. A wide variety of study designs were utilized to obtain the largest sample size available. Hilal et al [105] concluded that, in patients with PS, satisfactory pain improvement can be obtained by BoNT, LA plus CS, LA, or CS injection therapy.

Recommendations. The results of the studies indicate that BoNT-A injections are effective for pain relief in PS, a compressive neuropathy of the sciatic nerve. In the above studies on BoNT-A treatment for PA, the total dose ranged from 50 to 200 U incoA or onaA (most commonly, 100 U per muscle). Given the location of the piriformis muscle, injections into the muscle are difficult to perform properly and should be guided. In the above studies on BoNT-A treatment for PA, BoNT-A injections were guided by ultrasound, EMG, fluoroscopy and/or CT. The last two approaches required the use of contrast medium. In some studies, EMG was used for additional control of the position of the needle inside the muscle after it was initially guided by another imaging modality. Some co-authors of the consensus have experience in the application of ultrasound-guided (D.V. Dmytriiev, N.T. Segin, A.V. Filipskyi), or fluoroscopy-guided (D.V. Dmytriiev, M.V. Biloshytska, V.V. Biloshytsky) and CT-guided (M.V. Biloshytska, V.V. Biloshytsky) intramuscular piriformis injections. It is reasonable to perform preliminary diagnostic injections of local anesthetics, because the diagnosis of PS is sometimes challenging, and BoNT-A drugs are expensive. These procedures should be performed by well-trained physicians.

Occipital neuralgia

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) [106] describes occipital neuralgia (ON) as unilateral or bilateral paroxysmal, shooting or stabbing pain in the posterior part of the scalp, in the distribution(s) of the greater, lesser and/or third occipital nerves, sometimes accompanied by diminished sensation or dysaesthesia in the affected area and commonly associated with tenderness over the involved nerve(s).

Pain in ON has at least two of the following three characteristics: 1) recurring in paroxysmal attacks lasting from a few seconds to minutes, 2) severe in intensity, and 3) shooting, stabbing or sharp in quality. In addition, pain is associated with both of the following: 1) dysaesthesia and/or allodynia apparent during innocuous stimulation of the scalp and/or hair and 2) either or both of the following: a) tenderness over the affected nerve branches and b) trigger points at the emergence of the greater occipital nerve (GON) or in the distribution of C2. Moreover, pain is eased temporarily by local anesthetic block of the affected nerve(s).

ICHD-3 notes that the pain of ON may reach the fronto-orbital area through trigeminocervical interneuronal connections in the trigeminal spinal nuclei. ON must be distinguished from occipital referral of pain arising from the atlantoaxial or upper zygapophyseal joints or from tender trigger points in neck muscles or their insertions.

ON is more common in women than in men, with anxiety and depression being common comorbidities. Chronic ON debilitates patients, sometimes makes them disabled and can be resistant to treatment with many medications. Therefore, the search for effective treatment options for chronic ON is important. Common treatments that have been employed in the past include NSAIDs, tri-cyclic antidepressants, anti-epileptic medications, injection therapy using anesthetics and corticosteroids, neurosurgical resection such as rhizotomy at C1-C3, atlantoepistrophic ligament decompression of C2 dorsal root ganglion, and electrical stimulation of sensory distributions using subcutaneous surgical leads [107, 108]. A Pubmed search with the keywords “occipital neuralgia” and “botulinum toxin” keywords yields 29 publications (mostly literature reviews that mention treatment of NP with BoNT).

Kapural et al [109] described a series of six patients with severe ON who received conservative and interventional therapies, including oral antidepressants, membrane stabilizers, opioids, and traditional occipital nerve blocks without significant relief for an average of 42 months. The GON was localized by electric stimulation to deliver 50 U of onaA for each block (100 U if bilateral) as close as possible to the greater occipital nerve. Significant decreases in pain VAS scores and improvement in Pain Disability Index (PDI) were observed in five of six patients at four weeks following BoNT-A occipital nerve block. The median duration of pain relief was 16 weeks.