Original article

Ukrainian Neurosurgical Journal. 2024;30(4):57-63

https://doi.org/10.25305/unj.313077

Minimizing skull defects in retrosigmoid approach: precision mapping of the sigmoid sinus with mastoid emissary vein canal

Artem V. Rozumenko, Mykola V. Yehorov, Vasyl V. Shust, Dmytro M. Tsiurupa, Anton M. Dubrovka, Petro M. Onishchenko, Volodymyr O. Fedirko

Department of Subtentorial Neuro-Oncology, Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute, Kyiv, Ukraine

Received: 10 October 2024

Accepted: 04 November 2024

Address for correspondence:

Artem V. Rozumenko, Department of Subtentorial Neuro-Oncology, Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute, 32 Platona Mayborody st., Kyiv, Ukraine, 04050, e-mail: dr.rozumenko@gmail.com

Objective. The retrosigmoid approach is a commonly used cranial approach to the cerebellopontine angle lesions, vascular and nerve pathologies. This study aims to develop a practical technique for intraoperative mapping of the sigmoid sinus using the topography of the mastoid emissary vein (MEV) canal to improve the accuracy of retrosigmoid craniotomy, and minimize postoperative adverse outcomes.

Materials and methods. Consecutive patients who underwent retrosigmoid approaches for cerebellopontine angle occupying lesions from October 2023 through August 2024 were included in the study. Perioperative computed tomography (CT) was performed with a slice thickness 0.5 mm in the axial plane. The projection of the internal opening of the MEV canal onto the external surface of the mastoid process was determined as the posterior border sigmoid sinus and anterior border for craniotomy. Comparative analyses were performed using t-test and Chi-square test.

Results. A total of 20 patients were operated for neoplasms occupying the cerebellopontine angle using retrosigmoid approach. The average measured distance from the external opening of the MEV canal to the projection of sigmoid sinus posterior border was 9.36 ± 2.17 mm (range 6.3–13.20 mm). The postoperative CT data showed statistically significant differences between the study and control groups in measures of bone window (p = 0.057) and surrounding cranial defect (p < 0.001). The size of bone flaps was slightly similar in all groups (p = 0.114). The mean cranial defect in the study group was almost twice smaller than in the control group 22.4% vs. 44.5% respectively.

Conclusions. This study confirms the utility of mastoid emissary vein canal topography in improving the accuracy of retrosigmoid craniotomy. By facilitating precise sigmoid sinus mapping, the technique reduces the extent of bone removal and minimizes postoperative cranial defect.

Keywords: Mastoid emissary vein canal; retrosigmoid craniotomy; mastoid foramen; cranial topography

Abreviations: MF – mastoid foramen; MEV – mastoid emissary vein; RSA – retrosigmoid approach; RSC – retrosigmoid craniotomy; CPA – cerebellopontine angle; SS – sigmoid sinus

Introduction

The retrosigmoid approach (RSA) is a well-established cranial approach to the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), commonly used for the resection of various neoplasms, vascular anomalies, and cranial nerve pathologies [1]. Existing external anatomical landmarks for RSA, such as the occipitomastoid suture, asterion and mastoid foramen (MF), are known to be highly variable [2, 3, 4]. In rural surgical practices, this variability often necessitates a two-step retrosigmoid craniotomy (RSC), where initial bone removal over the cerebellar hemisphere is followed by further bone drilling to expose the venous sinuses. Precise craniotomy planning and intraoperative orientation are crucial for minimizing unnecessary cranial defects and reducing the risk of inadvertent sinus exposure, which carries a high risk of laceration [5, 6, 7].

Previous anatomical studies have revealed topographic variations in the mastoid emissary vein (MEV) canal in cadaver specimens, which offer valuable insights for improving surgical mapping and reducing the risk of excessive bleeding or thromboembolic complications during RSA [2, 3, 4, 8]. Efforts to delineate the posterior border of sigmoid sinus (SS) using alternative external anatomical landmarks, such as the digastric point, have not consistently clarified the trajectory of the superior aspect of the SS [5, 6].

Other studies have evaluated the accuracy of 3D CT reconstruction and navigation techniques in identifying the junction of the transverse sinus and SS during retrosigmoid craniotomies. These studies highlight the reliability of navigation based on anatomical landmarks while underscoring the limitations of using the asterion as a reference point [7, 8, 9, 10].

This study is aimed to develop practical technique of intraoperative sigmoid sinus posterior border mapping using topography of the MEV canal to facilitate precise maximally lateral craniotomy for cerebellar retraction and skull defect minimization.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study employed a prospective cohort design to investigate the efficacy and outcomes of SS mapping technique in RSA surgery. The study adhered to ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional review board approval.

Patient Selection

Consecutive patients who underwent retrosigmoid approaches for CPA occupying lesions from October 2023 through August 2024 were included in the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

Imaging

Perioperative CT was performed on Aquilion ONE (Toshiba, Japan) with a slice thickness of 0.5 mm in the axial plane and a 0.25 mm slice reconstruction interval.

Image processing

The CT data were processed using Horos 3.3.6 (Horos Project, GNU Lesser General Public License, Version 3). The data series were visualized in 3D MPR mode with a CT bone window regime (WL 300, W 1500).

The MF (external opening of MEV canal) was identified using axial scans in the horizontal plane. Subsequently, the angle of the horizontal plane was adjusted by manipulating the horizontal axis on sagittal images to align with the internal opening of the MEV canal. This maneuver allowed visualization of nearly the entire MEV canal length, clarifying its direction within the bone and its inclination angle.

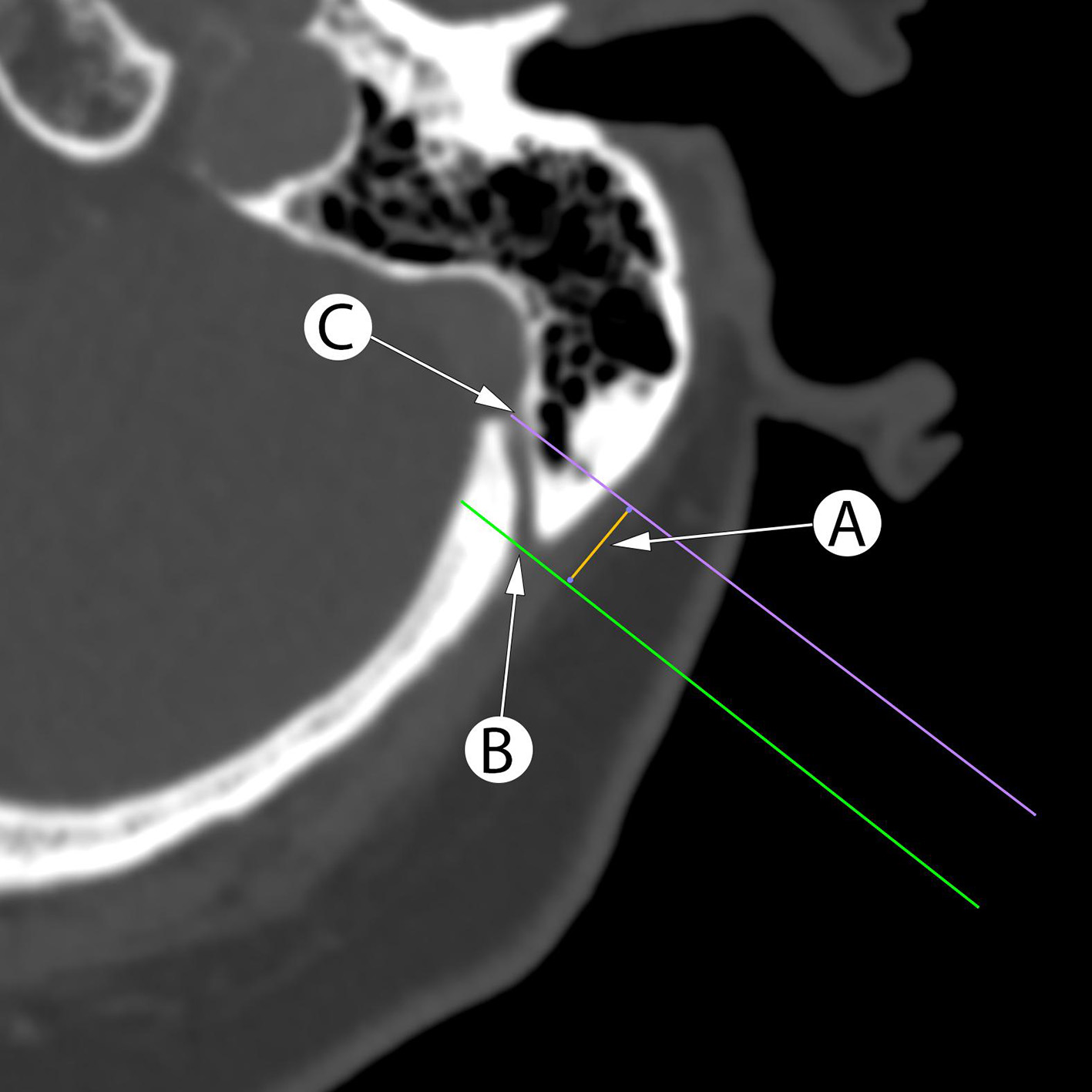

The projection of the internal opening of the MEV canal onto the external surface of the mastoid process was determined by constructing a perpendicular line to the external mastoid surface. The distance between the projection points and the MF was measured (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Planning the retrosigmoid craniotomy using axial CT scans with measurement of the distance (A) between perpendicular lines to mastoid surface between the mastoid foramen (B) and internal opening of the MEV canal (C) projection corresponds to projection of the sigmoid sinus posterior border

Surgical procedure

The RSA was performed in the park bench position with rigid head fixation. We used standard retroauricular slightly C-shaped skin incision with further periosteal dissection forming one soft tissue flap. After coagulation of MEV, the MF was sealed with bone wax. The posterior border projection of the SS at the level of MF was identified according to preoperative calculations. The line “A” connecting calculated point with digastric point was recognized as posterior border SS and anterior border for the craniotomy. The asterion was always selected as the upper border of planned craniotomy. The initial burr hole was placed over the cerebral hemisphere at the medial lower part of the surgical wound. After blunt dura separation, the bone cutting was performed with high-speed drill including asterion, MF and digastric groove in one or two step maneuvers without additional use of rongeurs to widen the craniotomy.

Data Collection

Patient demographics, short-term postoperative complications, and outcomes were documented. All clinical and neuroimaging data were stored in a local hospital database.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics, and outcomes were presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate. Comparative analyses were performed using Chi-square test for categorical variables, and the two-sample t-test was applied for comparing continuous variables. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 20 patients were operated on for СPA lesions using the RSA. The study group consisted of 10 patients where craniotomy was performed with MEV topography data (Tab. 1), other 10 patients were in the control cohort.

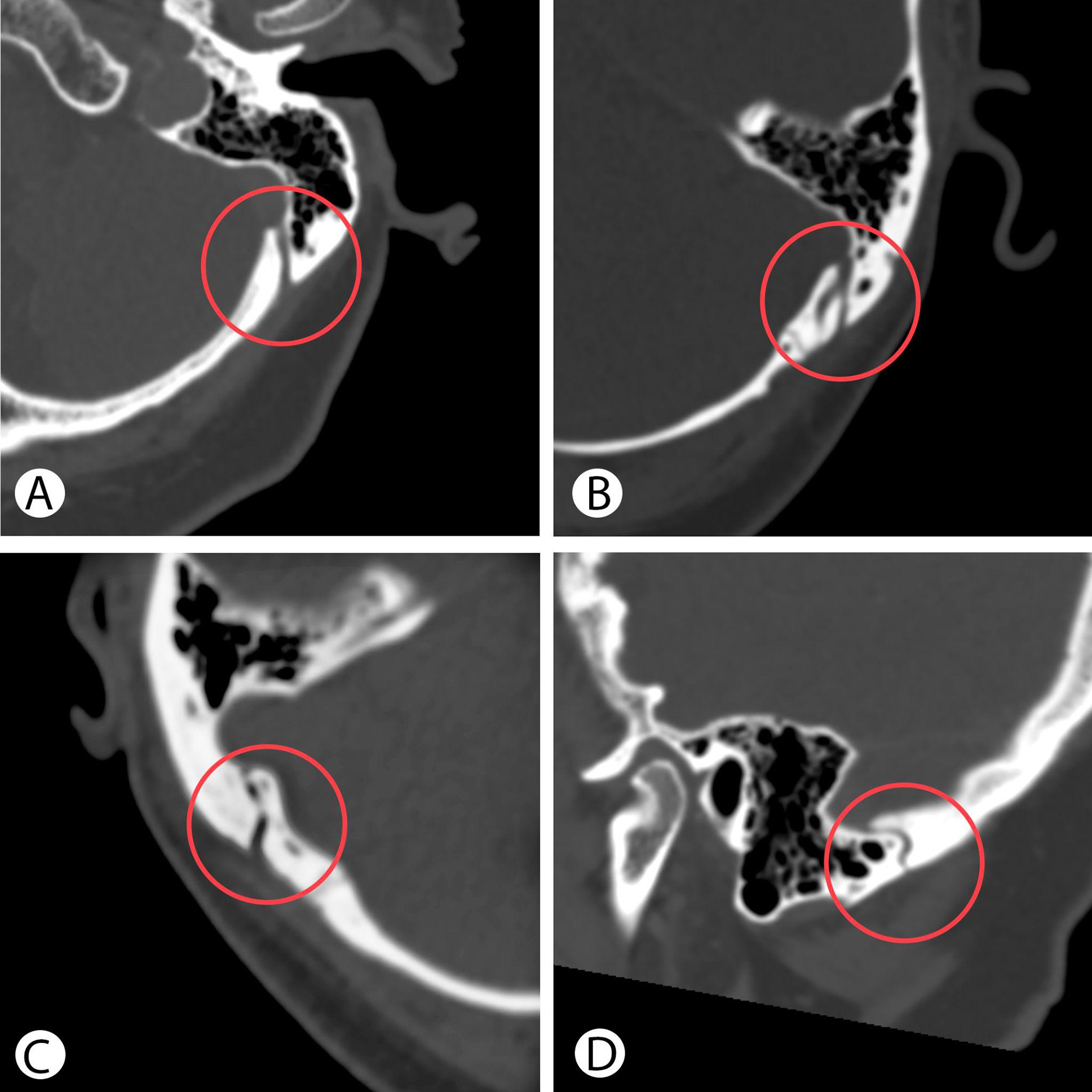

The MEV canal was presented in all cases of study group on CT as hypodense straight structure passing close to the Frankfort Horizontal Plane with one or two external openings (Fig. 2A and 2B). In our series only in 2 cases the MEV canal had curved “S” like form in axial or sagittal plane (Fig. 2C and 2D). The medium distance between external and internal MEV canal opening was 11.90 ± 1.18 mm (range 9.40–14.10 mm). The medium measured distance “A” from the external opening of the MEV canal to the projection of SS posterior border was 9.36 ± 2.17 mm (range 6.3–13.20 mm).

Table 1. Clinical and anatomical data of patients in the MEV topography study group

|

Case |

Side |

Age |

MEV canal length, mm |

MEV canal shape |

MF external opening, n |

Bone thickness, mm |

Distance to sagittal sinus, mm |

Bone flap square, cm2 |

Window square, cm2 |

Cranial defect, % to the whole craniotomy |

|

1 |

L |

28 |

11.60 |

S |

2 |

6.9 |

9.30 |

7.50 |

9.70 |

22.68 |

|

2 |

L |

53 |

13.60 |

S |

1 |

11.8 |

11.80 |

7.40 |

10.30 |

28.16 |

|

3 |

R |

72 |

12.30 |

C |

1 |

12.17 |

10.50 |

5.90 |

8.60 |

31.40 |

|

4 |

L |

59 |

11.10 |

S |

1 |

7.34 |

8.70 |

6.50 |

8.50 |

23.53 |

|

5 |

L |

56 |

14.10 |

S |

2 |

7.61 |

10.60 |

5.30 |

7.30 |

27.40 |

|

6 |

R |

39 |

9.40 |

S |

1 |

6.32 |

7.10 |

8.70 |

10.50 |

17.14 |

|

7 |

L |

63 |

11.30 |

S |

1 |

12.74 |

8.10 |

6.80 |

9.20 |

26.09 |

|

8 |

L |

37 |

11,5 |

S |

2 |

8.76 |

8.20 |

5.90 |

7.20 |

18.06 |

|

9 |

L |

26 |

14.10 |

C |

2 |

11.79 |

13.20 |

10.62 |

12.06 |

11.94 |

|

10 |

L |

34 |

9.6 |

S |

2 |

8.77 |

6.13 |

6.95 |

8.40 |

17.26 |

Fig. 2. Preoperative CT reveals the straight shape of the MEV canal in axial plane (A), with two external openings (B), a curved shape in axial (C) and sagittal plane (D).

Intraoperatively in all cases of study group the MEV was found on the retromastoid area as a thin-walled vessel with intact circulation. The intraoperative anatomy was consistent with the preoperative CT findings. The MEV was managed in standard fashion, dissected and coagulated followed by waxing of MF.

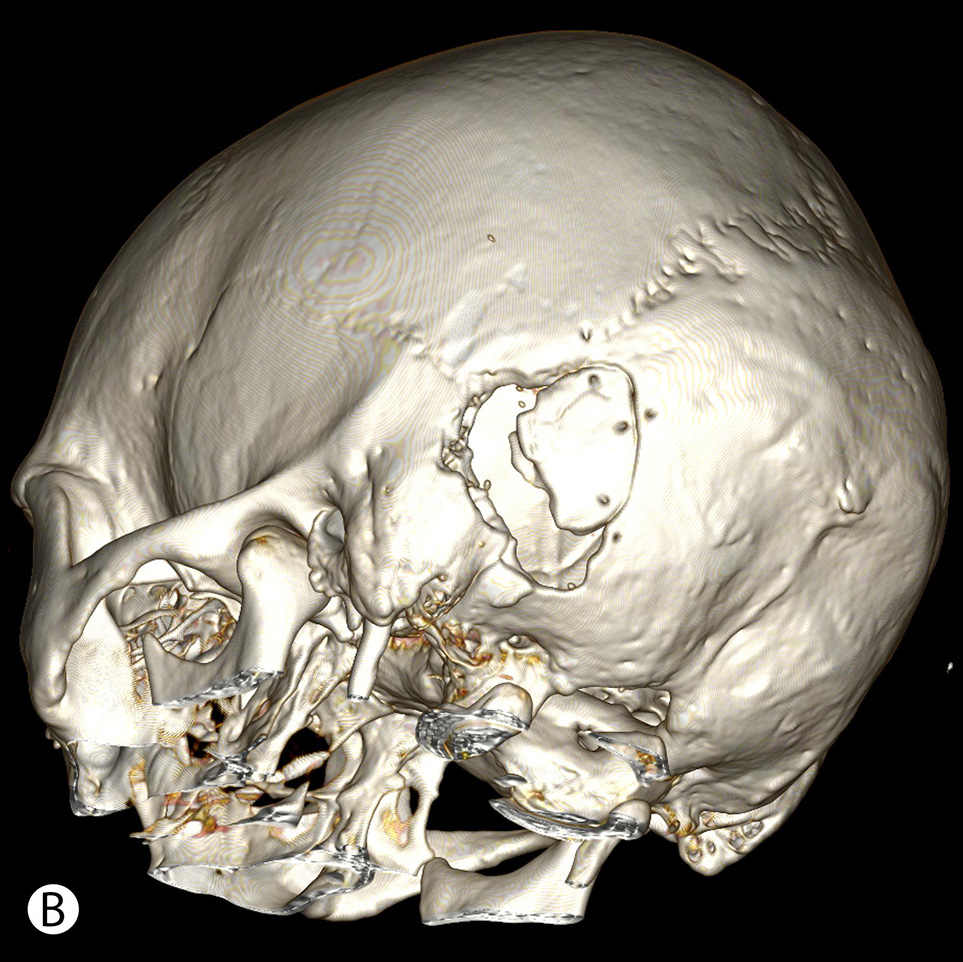

The postoperative CT data (Fig. 3) showed statistically significant differences between study and control groups in measures of bone window (p = 0.057) and surrounding cranial defect (p < 0.001). The size of bone flaps was slightly similar in all groups (p = 0.114). The data of calculations are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 3. Postoperative CT after retrosigmoid approach with the use of MEV topography shows minimal linear cranial defect (A), compared to a wide retromastoid defect due to additional bone removal after initially insufficient craniotomy (B)

Table 2. Comparison of demographic parameters and surgical outcomes between study and control groups

|

Descriptives |

Study group |

Control group |

P–value |

|

Number of patients, n |

10 |

10 |

– |

|

Median age, yrs |

47 |

54 |

0.236 |

|

Age range, yrs |

26–72 |

33–72 |

|

|

Mean bone flap ± m, cm2 |

7.16 ± 1.55 |

6.05 ± 1.41 |

0.114 |

|

Bone flap range, cm2 |

5.30–10.62 |

4.10–8.30 |

|

|

Mean bone window ± m, cm2 |

9.18 ± 1.51 |

10.93 ± 2.27 |

0.057 |

|

Bone window range, cm2 |

7.20–12.06 |

7.30–14.70 |

|

|

Mean cranial defect ± m, % |

22.26 ± 6.11 |

44.47 ± 7.21 |

< 0.001 |

|

Cranial defect range, % |

11.94–31.40 |

34.38–55.96 |

The mean cranial defect in the study group was almost twice smaller than in the control group (22.4% vs. 44.5%). Additionally, the maximal cranial defect in the study group was smaller than the minimal defect in the control group (31.4% vs. 34.4%).

Discussion

The retrosigmoid approach plays a crucial role in neurosurgery, providing access to the posterior fossa for various pathologies at CPA. Enhanced visualization on all CPA levels implies following the classical rule for exposition of the posterior margin of the SS as a lateral border of the RSC. The SS projection has an individual relation with external bone landmarks [3, 4, 8]. This fact provoked the profound study of regional anatomy of most prominent bone structures such as asterion, mastoid sulcus and mastoid foramen (MF) with its emissary vein to find the topographical patterns and prevent the complications caused by local venous system interruption [5, 6, 11, 13].

Tubbs et al. (2009) [8] performed a study aimed to enhance the precision of the RSC by investigating external bony landmarks on 100 adult skulls. The authors' technique included both side skull drilling from inside at the transverse-sigmoid sinus junction area. The position of the burr hole was measured from a well-defined horizontal zygomatic line and vertical mastoid line. The results indicated consistent patterns for left and right sides, but revealed variability of measured distances with a standard deviation of 8.35 mm for zygomatic line and 7.25 mm for mastoid line. These findings emphasize the significance of refining landmark data for accurate external localization of the area near the transverse-sigmoid sinuses for RSA planning.

The study of Hampl et al. (2018) [4], involving 295 skulls, comprehensively evaluated both quantitative and qualitative parameters of the MF. The MEV passing through the MF holds crucial neurosurgical significance due to its variable presence near the occipitomastoid suture, posing a risk of bleeding in surgical approaches through the mastoid process, particularly in RSA. The work reveals that expecting a variable location and number of mastoid emissary veins (MEVs), often with two external openings (41.2%). Internal openings predominantly occur as a single foramen (76%) with a median length of the MEV canal 9,3 mm. The work focuses on the prevention of dyshemic complications associated with venous system disorders and the need for preoperative neuroimaging to prevent predictable situations in the surgical field. However, the technical part of performing RSA, taking into account data on the individual anatomy of the MEV canal, was beyond the scope of these and other predominantly anatomical studies [2, 3, 11].

Neuronavigation supports transverse and SS mapping and helps in planning and performing RSA. The group of 30 patients was analyzed by da Silva et al. [9] showed prevalence of image-guidance over anatomical surface landmarks. In an even smaller group of patients, Hamasaki et al. [7] demonstrated the advantage of 3D reconstruction of CT data and the establishment of a topographic relations of the sinus projection to external bony landmarks without neuronavigation.

In 2021, Kubo et al. [6] proposed a line that is an extension of the digastric groove to determine the position of the initial burr hole for RSA. The aim of the study was to determine the safe zone of skull perforation outside the sinus passage in trigeminal neuralgia. Although the authors do not mention the use of neuroimaging methods to create access and perform a precise craniotomy. However, on the detailed diagram they show the significant variability in the location of external landmarks such as the asterion relative to the projection of the adjacent sinuses.

The study of Rosen et al. [12] focuses on the CT morphometric features of MEV. Through the evaluation of 100 consecutive patients with vestibular schwannomas, the research highlights notable anatomical variations in the number, size, and intraosseous length of MEVs, emphasizing the necessity of thin-slice CT for accurate preoperative planning. The detection rate of MEVs in thin-slice CT scans was significantly different from standard CT scans. Using thin-slice CT data the MEVs localization and diameter could be predicted to prevent surgical injuries.

The following studies by Hu et al. [10] proposed the use of a coordinate system based on 3D reconstruction of CT data. Several landmarks except asterion were identified and marked on the outer surface of the skull: the midpoint of the posterior edge of the external auditory canal, the apex of the mastoid process and the digastric groove apex. To locate the key point for burr hole above the sinus, the ratio of segments of the transected lines was calculated, instead of absolute values.

The publication of Hall [13] in 2019 summarized the results of previous morphometric studies. Eight methods of key point localisation were used on 50 models of 3D skulls. The authors prefer methods that allow the use of bone landmarks directly within the surgical field to reduce the possible errors due to the surgical draping and soft tissues. Although the selected techniques operate with the indents that are indicated in absolute numbers, the burr hole enhances surgical effectiveness while reducing the risk of complications linked to excessive exposure of venous sinuses or the creation of oversized bony defects.

The present study focused on clinical implementation of previously described cranial landmarks to develop a simple technique of precise RSA to avoid time-consuming bone removal, tearing of the sinus wall, and postoperative cranial defect. The distance between MF and projection point of the MEV confluence into SS, its most posterior border, allows one to choose the optimal position of the RSC.

Additionally, besides sinus mapping, our study considers that the modified RSC technique proposed by Choque-Velasquez and Hernesniemi [14] is less harmful and risky. According to the authors, for RSA a single burr hole is placed on the occipital squama over the cerebellar hemisphere at medio-caudal part of the planned bone window. This location of burr hole is simple to perform due to thinner bone and safer due to plain dura mater layers beneath. When classic RSA implies key hole drilling at the asterion area with thick bone and high risk of sinus wall perforation. If necessary, the basal extension of RSA to the condylar region was performed by craniotome forming a single bone flap to avoid additional bone removal in close to the sinuses.

The evolution of RSA went from rejection of bone flap removal in all cases for posterior fossa decompression to maximal preservation of surrounding tissue layers for better consolidation of surgical wound [2, 14, 1]. Further development of reliable and simple techniques for intraoperative orientation would have impact on surgery related risks levels and facilitate fast patient postoperative recovery.

Conclusion

This study confirms the utility of mastoid emissary vein canal topography in improving the accuracy of retrosigmoid craniotomy. By facilitating precise sigmoid sinus mapping, the technique reduces the extent of bone removal and minimizes postoperative cranial defect. These findings highlight the potential of this approach to enhance surgical safety and efficiency in cerebellopontine angle procedures.

References

1. Sepehrnia A, Knopp U. Osteoplastic lateral suboccipital approach for acoustic neuroma surgery. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(1):229-30; discussion 230-1. doi:10.1097/00006123-200101000-00046

2. Zhou W, Di G, Rong J, Hu Z, Tan M, Duan K, Jiang X. Clinical applications of the mastoid emissary vein. Surg Radiol Anat. 2023 Jan;45(1):55-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-022-03060-0

3. Chaiyamoon A, Schneider K, Iwanaga J, Donofrio CA, Badaloni F, Fioravanti A, Tubbs RS. Anatomical study of the mastoid foramina and mastoid emissary veins: classification and application to localizing the sigmoid sinus. Neurosurg Rev. 2023 Dec 19;47(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02229-4

4. Hampl M, Kachlik D, Kikalova K, Riemer R, Halaj M, Novak V, Stejskal P, Vaverka M, Hrabalek L, Krahulik D, Nanka O. Mastoid foramen, mastoid emissary vein and clinical implications in neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2018 Jul;160(7):1473-1482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3564-2

5. Raso JL, Gusmão SN. A new landmark for finding the sigmoid sinus in suboccipital craniotomies. Neurosurgery. 2011 Mar;68(1 Suppl Operative):1-6; discussion 6. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182082afc

6. Kubo M, Mizutani T, Shimizu K, Matsumoto M, Iizuka K. New methods for determination of the keyhole position in the lateral suboccipital approach to avoid transverse-sigmoid sinus injury: Proposition of the groove line as a new surgical landmark. Neurochirurgie. 2021 Jul;67(4):325-329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2020.12.009

7. Hamasaki T, Morioka M, Nakamura H, Yano S, Hirai T, Kuratsu J. A 3-dimensional computed tomographic procedure for planning retrosigmoid craniotomy. Neurosurgery. 2009 May;64(5 Suppl 2):241-5; discussion 245-6. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000336763.90656.2B

8. Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Shoja MM, Bellew MP, Cohen-Gadol AA. Surface landmarks for the junction between the transverse and sigmoid sinuses: application of the "strategic" burr hole for suboccipital craniotomy. Neurosurgery. 2009 Dec;65(6 Suppl):37-41; discussion 41. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000341517.65174.63

9. da Silva EB Jr, Leal AG, Milano JB, da Silva LF Jr, Clemente RS, Ramina R. Image-guided surgical planning using anatomical landmarks in the retrosigmoid approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2010 May;152(5):905-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0553-5

10. Hu W, Zhou J, Liu ZM, Li Y, Cai QF, Hu XM, Yu YB. Computed Tomography Study of the Retrosigmoid Craniotomy Keyhole Approach Using Surface Landmarks. Int J Clin Pract. 2023 Mar 1;2023:5407912. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5407912

11. Reis CV, Deshmukh V, Zabramski JM, Crusius M, Desmukh P, Spetzler RF, Preul MC. Anatomy of the mastoid emissary vein and venous system of the posterior neck region: neurosurgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2007 Nov;61(5 Suppl 2):193-200; discussion 200-1. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000303217.53607.d9

12. Roser F, Ebner FH, Ernemann U, Tatagiba M, Ramina K. Improved CT Imaging for Mastoid Emissary Vein Visualization Prior to Posterior Fossa Approaches. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2016 Nov;77(6):511-514. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1584208

13. Hall S, Peter Gan YC. Anatomical localization of the transverse-sigmoid sinus junction: Comparison of existing techniques. Surg Neurol Int. 2019 Sep 27;10:186. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_366_2019

14. Choque-Velasquez J, Hernesniemi J. One burr-hole craniotomy: Upper retrosigmoid approach in helsinki neurosurgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2018 Aug 14;9:163. https://doi.org/10.4103/sni.sni_186_18